On the other side of the world, in the tranquil emerald countryside just 10 miles south of Phnom Penh, Cambodia's capital, a modest Buddhist stupa with double-gilded eaves houses over 5,000 skulls, an infinitesimal fraction of the 1.7 million Cambodians tortured, starved or slave-labored to death by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge henchmen during their horrific years in power from 1975 to 1979.

Mute Witnesses to Horror in Rwanda and Cambodia: The Stations of the Skulls on the Looney Front

Huffington Post | 6 April 2014

As the world marks the 20th anniversary of the start of the

Rwandan genocide on April 6, the macabre human remains of that terrible

massacre have become grim stations of the cross on the tourist circuit

in the otherwise magnificently beautiful country -- just as they did

years earlier in another far-off country from whose experience humanity

failed to learn.

They are 5,250 miles apart, one in Asia, the other in Africa. But in

each, huge piles of human skulls bear mute witness to the genocidal

horrors of the last quarter of the 20th century, long after the world

should already have learned better from the enormity of the Nazi

Holocaust.

Both have been memorialized in books, documentaries and films -- Cambodia in the Killing Fields, Rwanda in Hotel Rwanda.

But nothing quite prepares you for the physical presence of the empty

eye sockets staring out in blind despair, the jaw-less mouths agape in a

silent shriek of agony.

If Cambodia's nearly four-year-long killing fields in the late 1970s

lacked the inter-ethnic connotations often attributed to genocide, the

same cannot be said of the horror that consumed Rwanda in 1994, when in

just 100 days beginning on April 6 Hutu extremists killed an estimated

800,000 Tutsi and the moderate Hutu who protected them.

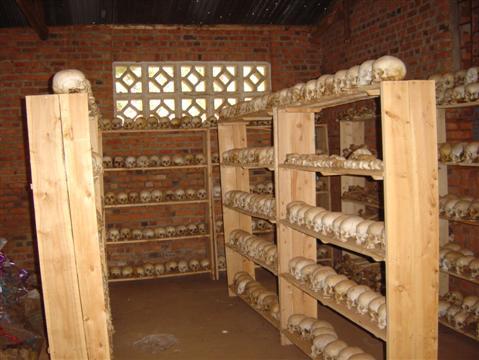

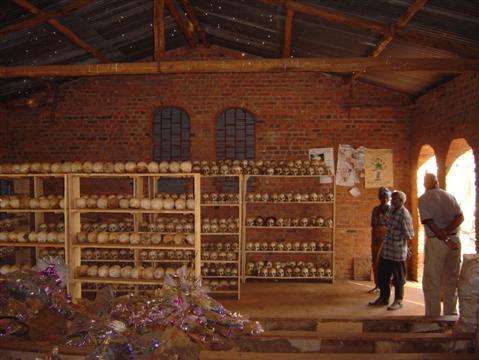

One such church is a raw brick-built rectangle in Ntarama, an hour's

drive from Kigali, Rwanda's capital. Here Hutu extremists first hurled

in grenades, then finished off 5,000 people crammed inside with guns,

machetes and clubs.

The victims still remain, still litter the floor with their bones

and shreds of clothing, their skulls piled high on shelves, an eternal

memorial to man's inhumanity to man.

All that is except one, Nyarabuzungu Dantsira, a woman who was saved

by being buried under an avalanche of corpses, among them her husband

and seven children.

A sign proclaiming "Never Again" in Kinyarwanda, French and English

has been fixed next to a hole breached in its wall above skulls, bones

and other remains honored with flowers beneath a green and purple

awning.

At a nearby church in Nyamata, skulls, bones and bloodstains on the

tin ceiling bear mute witness to 2,500 or more machine-gunned to death.

Many of these churches lie in spectacularly beautiful surroundings.

The little town of Kibuye climbs a promontory and extends along slivers

of land into Lake Kivu amid emerald mountains, limpid waters and

tree-garbed islets.

The St. Jean Catholic Church and Home Complex crowns a little

hilltop with magnificent views. Here in mid-April 1994 thousands of men,

women and children were hacked, bludgeoned and shot to death.

Today skulls and bones stare out from glass encased shelves built

into the church's front. A stone block directs you to another memorial

to 11,400 victims slaughtered in the nearby stadium on April 17.

If it is true that the human mind has difficulty in comprehending the

enormity of mass killings and it is the single example or a digestible

combination of them that really brings home the utter horror, then

nowhere is that more true than in the pink-painted Kigali Memorial

Centre in the capital.

Here, among the mass graves of 250,000 victims, among rooms devoted

in morbid solidarity to other 20th-century genocides, from the German

massacre of the Herero in Namibia at the start of that blighted century,

through the Armenian genocide and Nazi Holocaust, to the horrors of

Srebrenica, here among the skulls and bones, there is a section devoted

to children, with their pictures, a brief description of their likes and

cause of death.

Beneath the photo of an infant: tortured; hacked by machete, slashed by machete in his mother's arms, age nine months.

Here you can take in the true measure of the horror beyond the blur of numbers and statistics.

Beneath the photo of a pretty little girl: Ariane Umutoni, age: 4.

Favorite food: cake. Enjoyed: singing and dancing. Behavior: a neat

little girl. Cause of death: stabbed in her eyes and head.

For not-so-mute witnesses to man's inhumanity to man just cross the

continent to Sierra Leone. A young man stands in rags outside the Crown

Bakery café on Freetown's Lightfoot Boston Street begging for alms,

jagged stumps protruding where his hands should be.

He is one of thousands of survivors of a civil war that culminated

in 1999 in Operation No Living Thing, one of the most brutal episodes of

a monstrously brutal conflict that tore the little country apart in

more than a decade of massacres and blood-soaked coups.

Launched by the bestial Revolutionary United Front (RUF), the

operation claimed 6,000 lives alone in Freetown and destroyed large

swaths of the city. It was the climax of RUF's appalling atrocities that

left thousands of people without hands or feet, in a massive frenzy of

mutilation until West African regional forces, British troops and the UN

finally reestablished peace.

In Rwanda, too, you can find the mutilated survivor of its genocide,

where a slashing machete only succeeded in lopping off a limb and not a

life.

On the other side of the world, in the tranquil emerald countryside

just 10 miles south of Phnom Penh, Cambodia's capital, a modest Buddhist

stupa with double-gilded eaves houses over 5,000 skulls, an

infinitesimal fraction of the 1.7 million Cambodians tortured, starved

or slave-labored to death by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge henchmen during

their horrific years in power from 1975 to 1979.

Here at Choeung Ek, the most easily visited of Cambodia's killing

fields due to its proximity to Phnom Penh, nearly 9,000 Cambodians

annihilated by their fellow Cambodians were tossed into mass graves.

Human bones still abound in these fields where the skulls stare out from

layer upon layer behind acrylic glass.

Many of the victims came from a former school that the Khmer Rouge

converted into a mass torture chamber in Phnom Penh itself. Once the

Chao Ponhea Yat High School, Pol Pot turned it into Security Prison 21

(S-21), where of the nearly 20,000 who passed through its satanic doors

only a dozen survived. It was just one of scores of such hellholes where

prisoners were beaten, tortured with electric shocks, burned with

searing hot metal and water-boarded among other torments.

Today the nondescript building is the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

It, too, has its cupboards of skulls and a map of Cambodia formed of

skulls among rooms of floor-to-ceiling wall-to-wall photos of victims,

torture implements and cells.