Theary Seng, a Cambodian-American human rights activist and lawyer who lost both parents to the Khmer Rouge and testified against Nuon Chea in ECCC proceedings, told CNN the process was "political theater."

Top Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of crimes against humanity, face life sentences

CNN | 6 August 2014

Former Khmer Rouge

leaders Nuon Chea, the former Deputy Secretary of the Communist Party of

Kampuchea, and Khieu Samphan, the one-time President of Democratic

Kampuchea, have been found guilty by the Extraordinary Chambers in the

Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) of crimes against humanity. Both have been

sentenced to life imprisonment.

Thirty-five years after the fall of Cambodia's genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, believed responsible for deaths of at least 1.7 million people between 1975 and 1979, only a single person has been brought to justice over one of the 20th century's great atrocities.

That will change

Thursday, when two top leaders of the former Khmer Rouge regime will

hear verdicts for their alleged crimes against humanity, in the first

trial they face relating to their alleged activities in the 1970s.

The octogenarians in the

dock are Nuon Chea, the former Deputy Secretary of the Communist Party

of Kampuchea known as "Brother Number Two," and Khieu Samphan, the

one-time President of Democratic Kampuchea, the Khmer Rouge's state,

known as "Brother Number Four."

Prosecutors are seeking life sentences for the accused, who both deny guilt and are seeking acquittal.

The men were senior

leaders in the Khmer Rouge regime, which ruled Cambodia between 1975 and

1979. During that time at least 1.7 million people -- about a quarter

of the Cambodian population -- are believed to have died from forced

labor, starvation and execution, as the movement ruthlessly executed its

radical social engineering policies aimed at creating a purely agrarian

society.

Activist: Court did disservice to victims

Who is hearing the case?

The charges are being heard in Phnom Penh in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia

(ECCC) -- a special United Nations-backed tribunal that was formed in

2006 to prosecute senior Khmer Rouge leaders and other regime figures

responsible for especially heinous acts.

The "hybrid" tribunal --

officially "an ad hoc Cambodian court with international participation"

-- uses both Cambodian and international judges and staff employed by

the U.N. in order to ensure the trials are conducted to international

standards and to mitigate against the weakness of the Cambodian legal

system.

Eight years on, the ECCC has delivered only one verdict.

In the ECCC's Case 001, Kaing Guek Eav, commonly known by his alias, Duch, was sentenced to life imprisonment

following his 2010 convictions for war crimes, crimes against humanity,

murder and torture. He was the commandant of the notorious Tuol Sleng

S-21 prison in Phnom Penh, where more than 14,000 people died.

The verdicts on Thursday

in the case known as 002/01 will be the first time that senior leaders

of the regime have faced justice.

Who are the accused?

Nuon Chea, born in 1926,

was Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot's brother-in-law, and was considered his

right-hand man and a key ideologist throughout the regime's reign of

terror.

My hope and wishes were betrayed by those who destroyed the movement Nuon Chea, the Khmer Rouge's "Brother Number Two"

Trained in law in

Bangkok, the 88-year-old was second-ranked in the Communist Party of

Kampuchea (as the Khmer Rouge is officially known) and served a short

stint as Democratic Kampuchea's prime minister.

Prosecutors described

him as an extremist who "crossed the line from revolutionary to war

criminal responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of

Cambodians," according to the ECCC.

Following the collapse

of Democratic Kampuchea in 1979, he remained a leading Khmer Rouge

figure in the years the movement operated as a rebel guerrilla force in

Cambodia's west. He surrendered in 1998, striking a deal with the

government that allowed him to live as a free man near the Thai border

until his arrest in 2007, according to the ECCC.

In his final statement to the court,

Nuon Chea admitted he carried "moral responsibility" for events during

the period, but also affirmed his innocence, according to the ECCC.

"The CPK's policy and

plan were solely designed to one purpose only, to liberate the country

from the colonization, imperialism, exploitation, extreme poverty and

invasion from neighboring countries," he said.

"The CPK's policy was

clear and specific: it wanted to create an equal society where people

were the master of the country ... The CPK's movement was not designed

to kill people or destroy the country. My hope and wishes were betrayed

by those who destroyed the movement."

Like many other Khmer

Rouge leaders, Khieu Samphan studied in Paris, publishing his doctoral

dissertation on "Cambodia's economy and industrial development." On his

return home, he became a professor and then took on a senior government

position before joining the Khmer Rouge rebels.

In 1976, he became the

head of state of Democratic Kampuchea, and in 1987, years after the fall

of Democratic Kampuchea, he replaced Pol Pot as the head of the Khmer

Rouge after the former's retirement.

Throughout the trial,

he expressed remorse for the suffering of victims, at one point

offering Buddhist prayers for the souls of those who had died. But he

repeatedly expressed his position that he was merely a figurehead, with

no role in Khmer Rouge policy.

In his final statement,

he expressed his view that the court was pre-determined to find him

guilty. "[W]hatever I did was to uphold the respect for fundamental

rights, and build a Cambodia that was strong, independent and peaceful,"

he said. "Those who will decide on my case have refused to take into

consideration the truth, and now classify me as a monster."

What are the charges?

The charges they face

relate to alleged crimes against humanity committed in the course of two

forced mass population movements after the Khmer Rouge came to power,

and the alleged large-scale execution of officers and officials of the

previous Khmer Republic regime that was toppled by the Khmer Rouge.

Those who will decide on my case have refused to take into consideration the truth, and now classify me as a monster Khieu Samphan, the Khmer Rouge's "Brother Number Four"

The first phase of

forced movement was the evacuation of Phnom Penh that began on 17 April,

1975, and led to between 1.5 to 2.6 million people being driven from

their homes out of the city in all directions, mostly without knowing

their final destinations, according to documents provided by the ECCC.

Prosecutors allege that

about 20,000 deaths occurred during the evacuation -- half from

execution and half from starvation and exhaustion -- and say the

evacuees were subjected to systemic mistreatment, forced labor and

enslavement in their new rural cooperatives.

The evacuees were

vilified by the regime as "new people" -- those identified as

urban-dwellers, intellectuals or associated with anything foreign.

The second phase of

forced movements related to those from the central, southwest, west and

east zones of the country, which took place from September 1975 through

1977. Some were "new people" evacuated from urban areas, some were

allegedly associated with the former regime and others were members of

the mainly Muslim Cham minority, according to the ECCC.

Prosecutors argue that,

through their alleged role in the two phases of forced mass evacuations,

the accused played a key role in a criminal enterprise, and were guilty

of crimes against humanity including forcible transfer, murder and

persecution.

The pair are also facing

genocide charges related to alleged crimes against Vietnamese and Cham

Muslims, as well as other crimes against humanity and war crimes, in a

related ECCC trial -- 002/02 -- which began in Phnom Penh last month

after the court decided to break up the indictments against the men into

separate trials.

Time running out

The decision to split

the case, said Lars Olsen, legal communications officer for the ECCC,

was partly to make the lengthy, complicated proceedings more manageable,

but also to try to reach a conclusion on some of the charges during the

lifetimes of the accused and the victims.

Nuon Chea observed most

of the trial from a holding cell due to poor health, while two

co-accused did not make it through the entire trial.

Ieng Sary, the Khmer

Rouge's co-founder and former foreign minister who was known as "Brother

Number Three," died during the trial in March 2013, at the age of 87.

His wife, Ieng Thirith,

the Minister of Social Affairs during the regime, also stood accused,

but was eventually ruled mentally unfit to face trial.

"Brother Number One,"

the former General Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, Pol

Pot, died in 1998 before he could be brought to justice.

The three who have stood trial to date may wind up being the only people to be ever face justice for Khmer Rouge crimes.

(The court) was ... clearly the last, best hope for genocide justice in Cambodia. Craig Etcheson, Genocide Watch

The ECCC is

investigating two other cases, 003 and 004, involving five suspects who

are yet to be officially named -- one of whom is dead, according to

former ECCC investigator Craig Etcheson -- with no decision made as to

whether to proceed with the cases.

These cases targeted

those "most responsible" for the most serious violations of law, said

Etcheson, and were focused on mid-level Khmer Rouge cadres who

implemented the orders of the senior leaders.

Whatever the decision of

the international co-investigating judge considering the matter -- the

national co-investigating judge has recused himself from those cases --

the path ahead appeared complicated, he said.

"The government, and Prime Minister Hun Sen in particular, has voiced considerable opposition to Cases 003 and 004," he said.

"If the international

co-investigating judge orders one or more of the suspects in cases 003

and 004 to stand trial, it is also expected that the national

co-investigating judge will dispute that decision, and so the process

will move to the pre-trial chamber for the adjudication of that dispute.

Therefore we can expect that come what may, much litigation remains to

be contested."

There were no plans to

indict anyone not currently under investigation, said Olsen, adding the

work of the tribunal was expected to continue until at least 2019.

What closure will the process bring?

Etcheson, a war crimes

investigator who is president-elect of the group Genocide Watch, said

that public opinion surveys had consistently shown that a large majority

of the Cambodian public supported the ECCC process.

Most would expect life

sentences for the accused, he said, and would likely "welcome that

outcome as providing a measure of justice," he said, while acknowledging

the criticism the court has come in for.

The ECCC's glacial pace

in securing only one conviction in eight years of operation, at a cost

of $200 million, has been widely criticized -- especially given the

suspects were nearing the end of their natural lives.

Proceedings were halted

for long periods when national staff went unpaid, and in a country where

Prime Minister Hun Sen initially came to power as a Khmer Rouge

battalion commander before defecting, accusations of politicization have

dogged the process.

Theary Seng, a

Cambodian-American human rights activist and lawyer who lost both

parents to the Khmer Rouge and testified against Nuon Chea in ECCC

proceedings, told CNN the process was "political theater."

With upwards of two million people killed during the Khmer Rouge regime, a $200 million dollar tribunal works out to roughly $100 per murder victim. Surely that is not an excessive price. Craig Etcheson, Genocide Watch

Cambodians accepted

that, while life sentences were not particularly satisfying outcomes

when handed down to elderly men, it was all that could be delivered by

the process. However, while Cambodians did not expect perfect justice

from the tribunal, it had taken too long to put the senior regime

figures on trial, and what had been delivered by the tribunal was less

than acceptable, she said.

'An imperfect vessel'

Etcheson agreed the ECCC had "clearly been an imperfect vessel with which to deliver justice for the crimes of the Khmer Rouge."

Its two-headed nature

had rendered judicial decision-making "cumbersome and occasionally

contentious" and there was "an emerging consensus among legal analysts

that this model should not be replicated elsewhere due to these

inefficiencies."

"But under the

prevailing international and domestic circumstances at the time the

parameters of the court were negotiated, it was also clearly the last,

best hope for genocide justice in Cambodia," he said.

Criticisms of the cost

of the process seemed unfair, he said, as the expense and scope of the

tribunal had been deliberately kept low.

"I would suggest that

with upwards of two million people killed during the Khmer Rouge regime,

a $200 million dollar tribunal works out to roughly $100 per murder

victim. Surely that is not an excessive price to seek justice for such a

monumental crime."

On the allegations of

political interference in the process, he said Cambodian PM Hun Sen

faced the difficult task of "not just of delivering a sense of justice

for the crimes of the past, but also of maintaining social stability in

the present, and mending the tattered threads of society."

"This difficult

balancing act cannot be easy, though it is often rather blithely

dismissed by critics as a simple act of craven political convenience.

"But based on everything

I understand about Cambodia, there can be nothing simple about it.

Perhaps we should not be so quick to judge the formidable task of

rebuilding a destroyed people and nation."

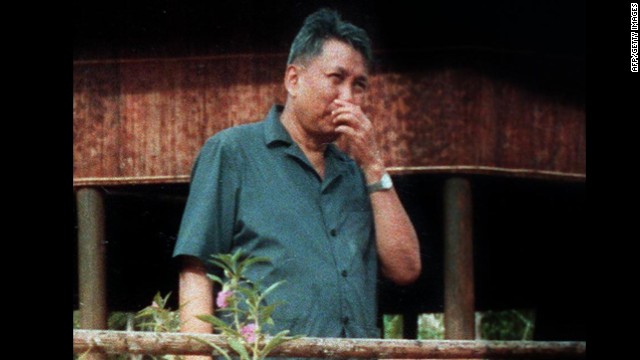

This undated photo,

which may have been taken in 1989, shows Pol Pot, the former leader of

the Khmer Rouge. He was under house arrest when he died in 1998 and

never faced charges for the slaughter under his reign.

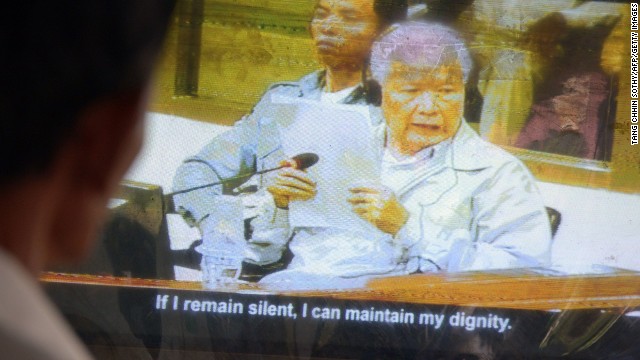

This undated photo,

which may have been taken in 1989, shows Pol Pot, the former leader of

the Khmer Rouge. He was under house arrest when he died in 1998 and

never faced charges for the slaughter under his reign. A Cambodian man

Khieu Samphan on a television during the trial at the Extraordinary

Chamber in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) in Phnom Penh on August 7. He

and Nuon Chea were found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced

to life in prison.

A Cambodian man

Khieu Samphan on a television during the trial at the Extraordinary

Chamber in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) in Phnom Penh on August 7. He

and Nuon Chea were found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced

to life in prison.

No comments:

Post a Comment