"The scars of the Khmer Rouge are very deep and physical and present in modern Cambodia," said Theary Seng, a human rights lawyer whose parents were killed by the regime, and who moved to the U.S. as a refugee before returning to her homeland as an adult.

She described the country as a "land of orphans."

Scars of the Khmer Rouge: How Cambodia is healing from a genocide

CNN | 16 April 2015

The silence was also due to the fact that Cambodians, in Seng's words, "lacked the vocabulary" of therapy and healing to process a crime of the magnitude of the one perpetrated against their society.

Story highlights

- Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, fell to the genocidal Khmer Rouge 40 years ago today

- At least 1.7 million people were killed in the subsequent four years, before the regime was driven out

- Decades on, the country is still struggling to gain justice for victims and heal from the genocide

On

the stage of a TV studio in Phnom Penh, Cambodian-American Ly Sivhong

is telling an engrossed audience a tragic, but familiar, story.

On

April 17, 1975 -- 40 years ago today -- life as Ly knew it was

shattered when her hometown, the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, fell

to the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime of the Communist Party of Kampuchea.

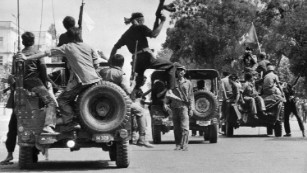

Khmer Rouge forces drive through Phnom Penh on 17 April, 1975.

Ly

never saw them again, nor learned what happened to them. But about

20,000 people died from execution, starvation or exhaustion during this

exodus at gunpoint, according to war crimes prosecutors; the others were

subjected to slave labor in rural camps once they reached their

destination, where many met similar fates.

The

urban evacuation marked the first phase in the Khmer Rouge's

revolutionary program of social engineering, intended to establish a new

order -- free of money, family ties, religion, education, property and

foreign influence.

Aimed

at creating an agrarian utopia, it would instead prove one of the worst

genocides of the modern era, resulting in the deaths of at least 1.7

million Cambodians -- about a quarter of the country's population --

over the next four years.

Family lost

Ly

remained in the capital with her father and four other siblings, three

of whom would succumb to starvation and disease in the following years,

before her father was shot to death before her eyes in 1979.

His

killing prompted Ly to leave her sole remaining family member, youngest

sister Bo, in the care of a local couple. She set out on her own,

making her way to a refugee camp and eventually to the United States.

Ly Sivhong beside her long-lost sister, Bo.

For more than 30 years she has wondered what happened to her baby sister.

"I think she was the only family member to survive," she says, with tears in her eyes.

As she finishes her story, the producers usher a woman on the stage. It's Bo.

Ly embraces her sister and both women sob.

"I missed you so much," Ly says.

"I've always searched for you," Bo tells her.

Land of orphans

Since

production began five years ago, the television show, "It's Not A

Dream," has reunited members of 54 Cambodian families shattered by the

genocide. More than 1,500 have sought its help.

The

series is just one example of the ways in which Cambodia's traumatized

society is beginning to undertake the fraught, painful business of

reckoning with their history.

A woman cries beside a dead body in Phnom Penh after fall of the city on 17 April, 1975.

"The

scars of the Khmer Rouge are very deep and physical and present in

modern Cambodia," said Theary Seng, a human rights lawyer whose parents

were killed by the regime, and who moved to the U.S. as a refugee before

returning to her homeland as an adult.

She described the country as a "land of orphans."

For

decades after the Khmer Rouge were driven from Phnom Penh by

Soviet-backed Vietnamese forces in January 1979, the regime's crimes

were seldom spoken about, let alone attempts made to seek redress for

victims.

In large part, this was because people remained scared, say experts.

Fear remains

Far from being snuffed out by the Vietnamese invasion, the Khmer Rouge existed for another two decades.

After fleeing the capital in 1979, Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot and his supporters established a stronghold in the west.

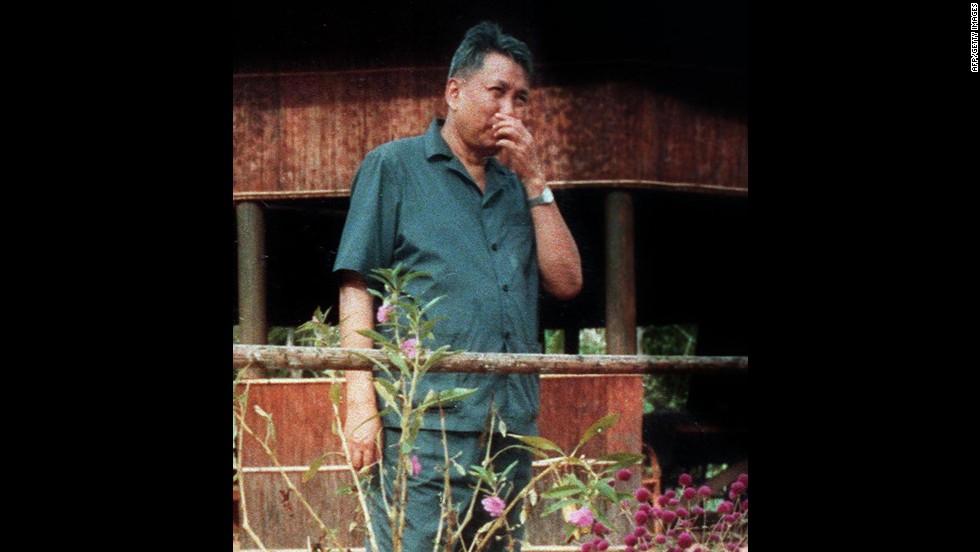

Pol Pot, former leader of the Khmer Rouge.

They

continued as an insurgent guerrilla force and became part of a

government-in-exile that, until 1990, was recognized by the U.N. as the

country's only legitimate representative.

"In

many villages, people have been living side by side with the

executioners for decades," said Krisna Uk, executive director of the

Center for Khmer Studies.

Craig

Etcheson, a Cambodia expert at the School for Conflict Analysis and

Resolution at George Mason University, said that "for many years, there

was a virtual taboo on even speaking of the Khmer Rouge, as if the very

words were ... a malevolent spirit lurking in the corner of every room."

How to heal?

The

silence was also due to the fact that Cambodians, in Seng's words,

"lacked the vocabulary" of therapy and healing to process a crime of the

magnitude of the one perpetrated against their society.

The

Khmer Rouge's attempts to reboot society at "Year Zero" had involved a

concentrated effort to exterminate the country's educated classes --

doctors, lawyers, accountants, engineers, merchants and clergy.

"Nearly

two generations of young Cambodian men grew up learning little more

than how to kill," said Etcheson. "When it was finally time to rebuild,

there were effectively no bootstraps with which the country could pull

itself up again."

Even today, said Uk, young Cambodians are not taught about the genocide in high school.

In

an impoverished country -- one of Asia's poorest, albeit with 7%

predicted economic growth this year -- most young people seemed to be

focused on getting ahead than looking back, she said.

Some

were even skeptical that the Khmer Rouge's crimes -- the systematic

butchery of the "killing fields" -- had really occurred, she added.

Cambodia's 'Nuremberg'

The

space for discussing, redressing and healing from the genocide only

began to open up in the past decade with the establishment of the Khmer

Rouge Tribunal, said Seng.

Founded in

2006, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) is a

"hybrid" tribunal using both Cambodian and international judges and

staff to investigate the Khmer Rouge's crimes against humanity and bring

leading regime figures to justice.

Intended

as a southeast Asian equivalent of the Nuremberg trials, the tribunal,

which has cost $232 million so far, initially enjoyed broad support.

"We

had great hope for this process," said Seng. "The presence of the

international community raised the comfort level of the population to

speak about the Khmer Rouge crimes."

But the pace of proceedings has seemed glacial, given the advancing years of the suspected war criminals, two of whom have died while facing trial. Another was ruled mentally unfit to stand trial. (The Khmer Rouge's top leader, Pol Pot, died in 1998, having never faced charges.)

This,

coupled with persistent accusations of political interference from the

Cambodian government, has soured attitudes towards the court.

Seng, who once appeared as a civil party in proceedings, today regards it as a "sham." For many victims, it is "too little, too late."

Three verdicts

In

the first case heard, Kaing Guek Eav, also known as Comrade Duch --

commandant of the notorious Tuol Sleng prison where more than 14,000

people were killed -- received a life sentence for war crimes, crimes against humanity, murder and torture.

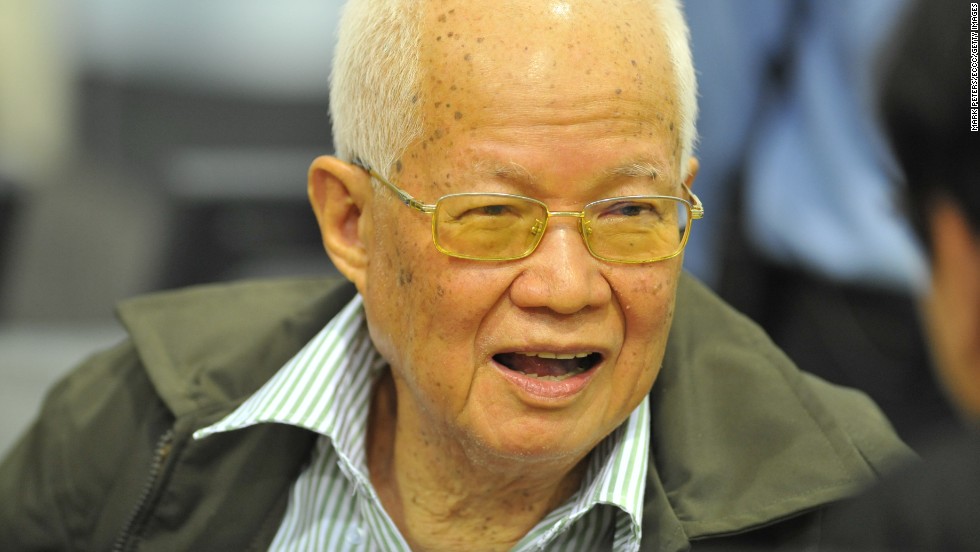

The court's only other verdicts, delivered in August last year,

sentenced Non Chea, the regime's "Brother Number Two," and Khieu

Samphan, "Brother Number Four," to life. Both men have appealed their

convictions.

Nuon Chea, "Brother Number Two."

In a separate case, the pair are on trial on additional charges of crimes against humanity and genocide. Evidence is expected to continue being heard into 2016, ECCC spokesman Lars Olsen said.

Two further, and highly controversial cases, known as 003 and 004, are also currently under investigation.

Three

people were charged last month in relation to those cases: former Khmer

Rouge navy commander Meas Muth; Im Chaem, a former district commander

accused of leading a labor camp; and Ao An, a former deputy accused of

overseeing massacres at detention centers. Two other suspects are being

investigated.

Olsen said no further cases would be pursued after 003 and 004.

'Imperfect vessel'

Prime Minister Hun Sen, Cambodia's strongman leader for decades, has long been a vocal opponent of 003 and 004, claiming that pursuing the cases could push the country towards civil war.

Hun

Sen himself is a former Khmer Rouge battalion commander, who defected

to the Vietnamese side; his perceived political interference is viewed

by critics like Seng as an attempt to shield political allies from the

tribunal.

Others are more forgiving of the tribunal's shortcomings.

Etcheson,

a former investigator for the tribunal, has described it as an

"imperfect vessel" for delivering justice, but says Cambodia's leaders

must strike a balance between two imperatives: delivering justice for

victims, and completing the reintegration of former Khmer Rouge into

society.

He said the most important

aspects of the tribunal's work are those that take place outside the

courtroom -- triggering changes in Cambodian society.

"In that respect, the proceedings ... may be shaping up to be more successful than anyone could have hoped," he added.

'Genocide memoirs'

Undoubtedly,

Cambodians today have overcome the fear of talking about the genocide

-- to the extent that even the perpetrators feel emboldened to say their

piece.

Krisna Uk said the country has

seen a wave of Khmer Rouge memoirs, written by former cadres wanting to

argue their case before they die.

"There's

a lot of people who want to tell the world they've been fooled by a

grand idea of a revolution which went bad," she said.

Khieu Samphan, "Brother Number Four."

Khieu Samphan, "Brother Number Four," published one such effort ahead of his trial,

while Sikoeun Suong, a Sorbonne-educated former diplomat for the Khmer

Rouge regime, published his "Journey of a Khmer Rouge Intellectual" in

French in 2013.

He told an interviewer from France's Le Monde last year that he believed that Khmer Rouge dictator Pol Pot's prescriptions for Cambodia were sound.

"I

remain convinced that the Marxist analysis made by Pol Pot of the

socioeconomic situation of Cambodia, a poor and sparsely populated

country, was correct," he said.

Bittersweet reunion

For survivors, these self-serving justifications for crimes gone unpunished must be hard to take.

But

for a few of them, at least, Cambodia's opening up about the genocide

has finally brought about the prospect of some healing, however

bittersweet.

Ly Sivhong is reunited with her mother, decades after she believed she had been killed.

On

the stage of the "It's Not a Dream" studio, as Ly hugs her long-lost

sister, footage of an even older woman is projected on a screen.

"Do you know the person in the video?" the show's host asks.

"Yes," Ly says. "She is my mother."

Moments later, Te Souymoy, 77, is brought up on stage.

"Where have you two been?" Te asks. "I always worried about you two."

"I thought you died," Ly says.

The three women cry and embrace.

"It is very miserable for all of us," the old woman says.

No comments:

Post a Comment