Towards Cambodia’s Great Lake

Luc Forsyth and Gareth Bright have set out on a journey to follow the Mekong river from sea to source. The Diplomat will be sharing some of the stories they’ve found along the way. For more about the project, check out the whole series here.

* * *

“I need you to put me in a car and send me back to Phnom Penh,”

Gareth said over the phone at 5 am. Our hotel rooms were only separated

by a single flight of stairs, but it was clear from his drained voice

that he didn’t have the strength to handle the short walk. In the

mid-sized city of Kampong Chhnang, located on the western bank of

Cambodia’s Tonle Sap river, the “A River’s Tail” project was about to

suffer its first casualty.

A young boy sleeps in a hammock inside his family’s house boat in the riverside city of Kampong Chhnang. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

We had taken a bus from Phnom Penh the day before, diverging from the

Mekong to explore the Tonle Sap, and Kampong Chhnang was meant to be a

brief stopover before taking a short boat ride to the remote riverside

community of Tae Pi. Arriving in the late afternoon, we spent the

remaining daylight hours wandering along the waterfront, shooting

pictures of daily life and speaking to locals about the health of the

all important waterway. They, like nearly everyone we had spoken to

during our travels, told of declining fish stocks and the corresponding

economic hardships.

A

man allows his dog to take a drink and eventually a dip in a public

fountain in Kampong Chhnang along the town’s riverside promenade. Photo

by Gareth Bright.

The lack of prosperity was plain. Despite being the most important

river port between Cambodia’s two largest cities — Phnom Penh and Siem

Reap — the city was shrouded in an air of lethargy, made all the more

sluggish by the sweltering heat of the dry season. While people went

about their daily tasks — mending fishing nets, loading manufactured

goods onto waiting boats, and socializing along the promenade — the

atmosphere was defined by a distinct lack of bustle.

Locals

in Kampong Chhnang play petanque, a French version of lawn bowling that

was made popular in Cambodia during the French colonial period. Photo

by Luc Forsyth.

As the sun set on the provincial capital, Gareth’s deterioration

became increasingly apparent from his colorless face. Hoping that a long

sleep in an air-conditioned room would restore him to health, we

returned to our hotel earlier than usual. Yet when my phone rang the

next morning I knew that it hadn’t worked. That early in the morning

there were no taxi drivers available to pick him up, so I spent a few

hours wandering along the banks of the river watching the city wake up

as children arrived to school on water taxis.

Workers carry ceramic tiles to a local ferry in the riverside city of Kampong Chhnang. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Eventually I managed to find a driver willing to take Gareth back to

Phnom Penh, and I helped him settle into the backseat with two liters of

water and a can of Coke. With Pablo locked in his office in the capital

working feverishly to edit the video footage from the Vietnam leg of

the project, for the first time since “A River’s Tail” began I was on my

own.

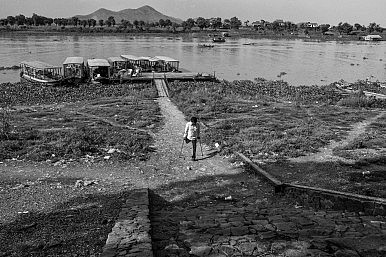

A

young boy walks towards the Mekong to collect water for his family in

the remote community of Tae Pi. During the dry season the river level

can recede up to a kilometer away from resident’s homes. Photo by Luc

Forsyth.

Old Friends and Parched Earth

The real reason we had stopped in Kampong Chhnang was so we could

visit Jan Ta and her family, whom Gareth and I had met 7 months

previously while driving a wooden fishing boat through Cambodia’s

waterways. It was that three-week trip that was the foundation for what

would become the “A River’s Tail” project, and meeting Jan Ta in the

remote community of Tae Pi where she lived had been one of the

highlights. When I called her again, even after more than half a year

without contact, she immediately agreed to send her son to fetch me in

Kampong Chhnang.

Jen

Ta, a resident of the village of Tai Pi prepares an early morning

breakfast of dried fish and rice for her family. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Our relationship had started by accident when Gareth and I, caught on

the water as the sun set and desperate to find a place to spend the

night, made an impromptu stop at a small cluster of homes along the

river’s edge that we spotted through our binoculars. When we had pulled

up to the shore, the initial reaction of the villagers had been one of

suspicious apprehension: Who are you and what do you want? This was not a

place that foreign tourists frequented, and the locals had eyed us

warily. But after a series of phone calls to a Khmer friend who was able

to explain that we were just seeking a place to sleep, the mood shifted

immediately. All hostility vanished and the nearest villager, Jan Ta,

had welcomed us into her home.

At that time, during the wet season when the river was at its highest

level, Tae Pi had been a picture postcard of simple riparian life. A

cluster of 30 families lived in stilted wooden houses along the river’s

edge, fishing from the river and gathering aquatic vegetables and

flowers to sell at nearby markets. The contrast that greeted me on my

return could not have been more pronounced.

A teenager drives his boat between the city of Kampong Chhnang and the remote village of Tae Pi. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

As Jan Ta’s 16-year-old son throttled the engine of his boat to full

speed and smashed through a thick barrier of lilies, I thought we were

making a quick stop somewhere before continuing on to Tae Pi. There were

no houses in sight, only a wide expanse of dry brown fields stretching

for a kilometer or more towards a small mountain on the horizon. This

did not in any way resemble the village I remembered, and it wasn’t

until Jan Ta’s son tied the boat up to shore and beckoned me to follow

that I understood that we had arrived. While I knew that Cambodia was

subject to dramatic environmental changes between seasons, the

transformation of the land rendered the area more unrecognizable than I

could have imagined.

A

young girl watches on as the small herd of cattle are herded early

morning in remote village of Tae Pi. Photo by Gareth Bright.

During

the heat of the day, a teenager relaxes under the shade of his family

home. Temperatures can approach 40 degrees Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) on a

daily basis during the dry season. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Dwindling Prospects

“The rainy season is much better,” Jan Ta said after I commented on

the transformation of the village. “In the dry season I can’t earn any

profits. It is impossible to catch fish, so I have to rent half a

hectare of rice field just to have enough food.” Though she seemed

genuinely happy to see me, there was a worn look on her face that I

hadn’t seen the last time we’d met and I suspected that all was not

well.

A

soldier, who works part time as a fisherman to earn extra money, mends

his nets in the riverside city of Kampong Chhnang. Photo by Gareth

Bright.

“This place has completely changed in the last 10-20 years,” she told

me, launching into a categorical list of her woes almost immediately

upon my arrival: “People are using fishing nets so fine that no baby

fish survive to grow up and be caught again. They are also using

batteries to shock the water, which kills everything. The farmers now

use chemicals on the rice, which goes into the water and poisons the

fish.”

A

teenage boy practices volleyball on a dry patch of ground in the remote

village of Tae Pi. During the rainy season, these fields would be

innundated by water. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

As Jan Ta spoke, I realized that the quaint memory I’d created of a

community living in harmony with nature was an illusion. The drastic

metamorphosis of the landscape only served to exacerbate the revelation

that I had remembered the village as I had wanted to — a stereotypical

idyllic memory that was rapidly being dispelled.

“I don’t know about the future of the river, but I can barely find

anything in it these days,” Jan Ta continued. “If the river can’t

support us now, I don’t have much hope for my kids. They will need to

leave here and get a job somewhere else. I have already sent my eldest

son to Phnom Penh to work in a garment factory so he can send money

home.” A new reality of life along the Tonle Sap, one of the most

important sources of fertility for the Mekong, was taking shape. And

like most of the stories we had found during our travels thus far, the

overall picture was not good.

A woman sits in on the porch of her stilled house in riverside town of Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia. Photo by Gareth Bright.

I left Jan Ta’s house for a few hours to walk through the village,

hoping that some time alone would allow me to make the necessary

adjustments to my perception of a place I had once thought so timelessly

quaint. I realized that I had made the mistake common to so many

travelers: in my eagerness to see what I wanted to see I hadn’t been

critically objective in my observations. I had tricked myself into

thinking Tae Pi was a model for how people could live happily from the

bounties of nature. The truth was that these people, like so many others

along the Mekong and its distributaries, were reeling from the

consequences of the human overexploitation of the river’s finite

resources — resources that were clearly at their breaking point.

A

fisherman catches his net on a sunken tree branch while fishing in the

early morning in the city of Kampong Chhnang.

Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Photo by Luc Forsyth.

That night Jan Ta prepared a meal of rice, fried fish, and eggs, ever

the good host despite the obvious challenges her family was facing. I

tried not to let the pervading sense of sadness, which I had felt since

readjusting my views on the realities life in this remote village, come

through; but Jan Ta seemed to see through me.

“I like it here,” she said. “Even if it is impossible for me to earn enough money, I will stay.”

This piece originally appeared at A River’s Tail.

No comments:

Post a Comment