How being alone may be the key to rest

BBC Radio 4 | 27 September 2016

Last November an online survey

called The Rest Test was launched to investigate what rest means to different

people, how they like to rest and whether there is a link between rest and

well-being. The results are now in and the analysis has begun.

Rest sounds easy to define, but

turns out to be far from straightforward. Does it refer to a rested mind or a

rested body? Actually, it depends. For some, the mind can't rest unless the

body is at rest. For others it is the opposite. It is the tiring out of the

body through vigorous exercise that allows the mind to rest - 16% of people said

they find exercise restful.

Altogether,

18,000 people from 134 countries made time to take part in what was quite a

lengthy survey devised by Hubbub - an international group of academics,

artists, poets, and mental health experts - showing perhaps what a pressing

issue rest is in the modern world.

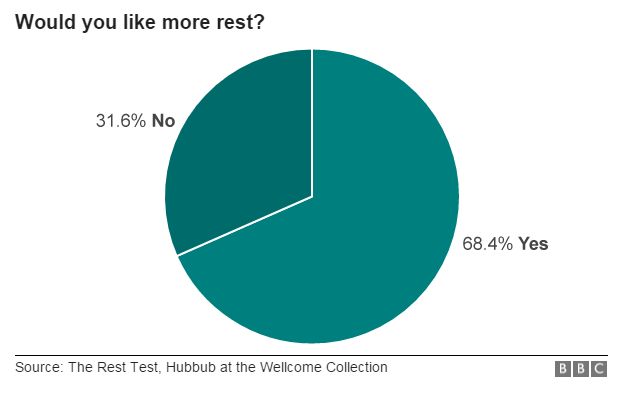

Just over two-thirds of

respondents said they would like more rest. Almost a third thought they needed

more rest than the average person, while 10% thought they needed less than

average.

One question asked people how

much they had rested the previous day, leaving them free to define rest in any

way they wanted to. The average was three hours and six minutes.

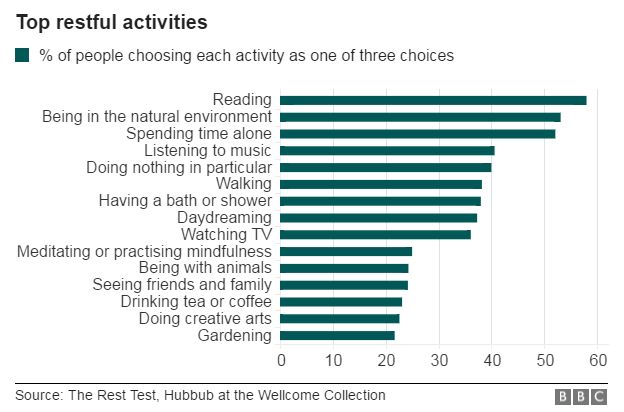

Another gave people a long list

of activities, asking them to rank the three most restful - and the results

were unexpected.

Reading came out as the clear

winner, followed by being in the natural environment, being on your own,

listening to music and doing nothing in particular.

What is striking is that all

these are activities often done alone.

Seeing friends and family,

chatting or drinking socially all come much lower down the list. This doesn't

mean that the respondents don't like socialising, but that they don't consider

it to be particularly restful.

Interestingly, this applies

both in the case of extroverts - sometimes defined as people who gain energy

from being around others - and introverts, who find other people draining.

Extroverts do place chatting and socialising a little higher up the chart, but

still they are beaten by solitary activities.

We need to remember, of course,

that choosing to be alone is very different from enforced loneliness.

- The Rest Test is a collaboration

between BBC Radio 4 and the Wellcome Collection's researchers in

residence, Hubbub

- Hubbub is an international

collective led by Durham University, comprising scientists, artists,

poets, humanities researchers, mental health experts and social scientists

- among them the BBC's Claudia Hammond, presenter of All in the Mind

- Some 18,000 people from 134

countries took the survey - they were self-selecting, not randomly chosen

- The biggest survey of rest before

this was a fraction of the size, based on data from little more than 1,000

people.

The reason people

want to be alone might be explained by the answers people gave when they were

asked what is going on in their minds while they do different activities.

"People

said that when they were on their own mostly they were focused on how they were

feeling, so on their body or their emotions," says Ben Alderson-Day, a

psychologist from the University of Durham, who co-wrote the survey.

The idea that when people are

alone they are mentally talking to themselves is only partly true, it seems.

"People said they were only

talking to themselves in their head 30% of the time," says Alderson-Day.

"There is a hint that when

you're on your own, as well as switching off from other people, you get the

chance to switch off from your own inner monologue as well."

But just because we're on our

own doing nothing, that doesn't mean the brain is resting. Neuroscientists used

to think that the brain was less active whenever we stopped concentrating on a

task, but late in the 20th Century studies using brain scanners threw up some

curious findings and they realised they had got it wrong.

When we are at rest, supposedly

doing nothing, our minds have a tendency to wander and our

brains are in fact busier when we're not concentrating on a task, than when

we are.

These days it's common to hear

the complaint that rest is hard to find. So what if we don't have enough time

to do these restful activities? Does it matter?

Possibly.

- You can hear more on the results

in The Anatomy of Rest on BBC Radio 4 - listen

online here

- The 10 most restful activities

- A free exhibition, Rest & its discontents, will be held at

Mile End Art Pavilion in London from 30 September to 30 October

- Hubbub's other work on rest, The

Restless Compendium, is free to download from 27 September

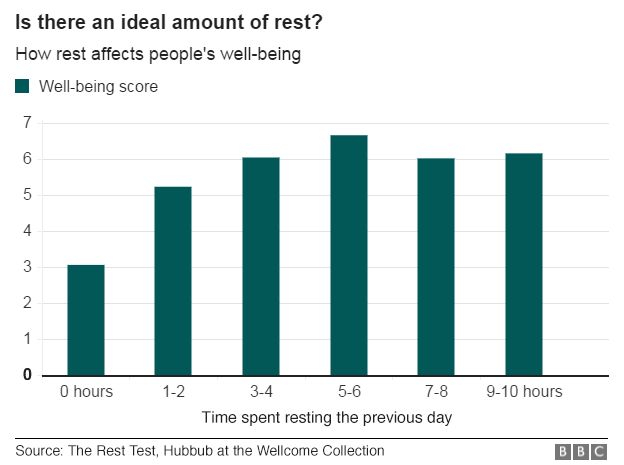

In the Rest Test

people who had fewer hours of rest the previous day score lower on a well-being

scale.

In fact people

who don't feel in need of more rest have well-being scores twice as high as

those who feel they need more rest. This suggests that the perception of rest

matters, as well as the reality. If we don't feel rested, our well-being is

lower.

People with the

highest well-being scores rested on average for between five and six hours the

previous day. If they had more rest than this, their scores began to dip

slightly. Might this suggest that enforced rest - if you are unemployed,

perhaps, or unwell - does not have the same impact on well-being? Perhaps five

to six hours is an optimum amount of time to rest.

Of course, large as this survey

is, it gives us a snapshot in time. So we can't be certain that the rest or

lack of it had an impact on the well-being scores. Is it possible that,

instead, high well-being scores make us feel rested? The relationship between

rest and well-being is striking, though.

It was notable that when asked

which words they associated with rest, almost 9% of people chose

"guilty" or even "stress-inducing". Yes, rest seems to make

some people worry about the things they aren't doing.

Prof Felicity Callard of Durham

University, director of Hubbub, says: "We really need to challenge the

assumption that if you take more rest, you are more lazy. The fact that people

who are more rested seem to have better well-being is an endorsement for the

need for the rest."

|

| Younger people are more likely to relax by listening to music |

So who gets the

most rest? Based on how many hours people told us they rested for in the

previous 24 hours, the least rested group were likely to be younger, working

traditional full-time hours or doing shift work that includes nights. They were

also more likely to have higher incomes or to be carers, while the most rested

group were more likely to be older, with lower incomes, unemployed, retired or

working split shifts - where people work for several hours, then have free time

and go back much later in the day or evening.

Men were more

likely to say they get less rest than the average person - but actually

reported getting 10 minutes more rest than women, on average, the day before

taking the survey.

What does rest look like to you?

We'd like to see

your photographs of how you rest, from kicking back in an armchair to something

more energetic. What works for you?

Send your

pictures to yourpics@bbc.co.uk or upload them via this link

Please add the

word Rest in the subject line of your message.

Once again,

perceptions of rest could come into it. Busyness has become a badge of honour

in today's society. To be busy is to be wanted and valued. When someone asks us

how we are and we answer, "Busy, so busy," how much is our answer to

do with status? Are people with high incomes more likely to want to claim to be

busy? Or is it that they have jobs where new technology means that the boundaries

between work and rest become ever more blurred, leaving them with the feeling

that they can't fully switch off?

The answer to

another question might shed light on this. People were asked to what extent

they believe rest is the opposite of work. The majority of those employed

full-time answered that rest was the opposite of work, but people who were

self-employed or volunteering were less likely to think it was. Does control

over your work affect whether it can ever be seen as restful, even if you're lucky

enough to enjoy your work?

A full analysis

of the data will be published within the next year. It's already clear that it

holds lessons for doctors. Callard points out that when doctors prescribe rest,

not every patient will interpret the word in the same way.

"There's a

desire clinically to be more precise about what you are prescribing when you

prescribe rest. But you need to find out what that particular individual finds

restful. Simply telling some people to go and do nothing is likely to provoke

anxiety rather than restfulness."

Many people, it

seems, would like to have more time to rest but perhaps it's not the total

hours resting or working that we need to consider, but the rhythms of our work,

rest and time, with and without others.

To truly feel rest

do we need time alone without fear of interruption, when we can be alone with

our thoughts? From the Rest Test, it would appear so.

It's only recently that

sleeping and doing very little - the ways human beings have always rested -

have come to be seen as an insufficient response to life's difficulties.

No comments:

Post a Comment