The Economist explains economics

The relationship between trade and wages

This week “The Economist explains” is given over to economics. For

each of six days until Saturday this blog will publish a short explainer

on a seminal idea.

The Economist | 4 Sept. 2016

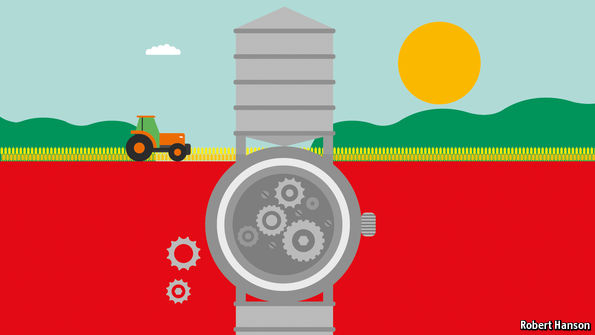

DOES trade hurt wages? Or, more precisely, do imports from low-wage

economies hurt workers in high-wage ones? Many people assume so.

Economists take a bit more convincing. Back in the 1930s, one trade

economist, Gottfried Haberler, argued that “the working class as a whole

has nothing to fear from international trade”—at least in the long run.

This confidence rested on three observations. Labour, unlike many

other productive resources, is required in all sectors. It will thus

remain in demand however much globalisation shakes up a country’s

industrial mix. Over time, labour is also versatile. Workers can move

and retrain; new entrants can gravitate towards sunrise sectors rather

than industries in decline. Finally, workers are also consumers, who

often buy the foreign goods in local shops. Even if competition from

cheap imports drives down their (nominal) wages, they will come out

ahead if prices fall by even more. Haberler’s confidence was not

universally shared, however. Wolfgang Stolper, a Harvard economist,

suspected that competition from labour-abundant countries might hurt

workers elsewhere. In 1941, he teamed up with Paul Samuelson, his

Harvard colleague, to prove it.

Their Stolper-Samuelson theorem

concluded that removing a tariff on labour-intensive goods would depress

wages by more than prices, hurting workers as a class, even if the

economy as a whole gained. The theorem’s logic rests on the interaction

between industries with different degrees of labour-intensity. It is

perhaps best explained with an example. Suppose a high-wage economy were

divided into two industries: wheat-growing (which is land-intensive)

and watchmaking, which makes heavy use of labour and shelters behind a

10% tariff. If this protection were removed, watch prices would fall by

10%. That would force the industry to contract, laying off labour and

vacating land. That in turn would put downward pressure on wages and

rents. In response, wheat growers would expand, taking advantage of the

newly available land and labour. This dance would continue until

watchmaking’s costs had fallen by 10%, allowing the industry to compete

with tariff-free imports.

Trade

liberalisation, in this example, depresses wages by more than prices,

hurting labour in real terms. This gloomy conclusion has proved

remarkably influential. It appears even 75 years later in debates about

the Trans-Pacific Partnership between America and 11 other countries,

many of them low-wage economies. Some economists regret this influence,

arguing that the theorem’s crisp conclusion does not hold outside of the

stylised settings in which it was first conceived. Even the theorem’s

co-author, Paul Samuelson, was ambivalent about the result. “Although

admitting this as a slight theoretical possibility,” he later wrote,

“most economists are still inclined to think that its grain of truth is

outweighed by other, more realistic considerations.”

Previously in this seriesMonday: Akerlof's market for lemons

Coming up

Wednesday: The Nash equilibrium

Thursday: The Keynesian multiplier

Friday: Minsky's financial cycle

Saturday: The Mundell-Fleming trilemma

Wednesday: The Nash equilibrium

Thursday: The Keynesian multiplier

Friday: Minsky's financial cycle

Saturday: The Mundell-Fleming trilemma

Over the past several weeks The Economist has run two-page briefs on six seminal economics ideas. Read the full brief on the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, or click here to download a PDF containing all six of the articles.

No comments:

Post a Comment