What is the impossible trinity?

This week “The Economist explains” is given over to economics.

Today’s is the last in a series of six explainers on a seminal idea.

IN THE run-up to the launch of the euro, in 1999, aspiring members pegged their currencies to the German mark. As a consequence they were obliged to shadow the Bundesbank’s monetary policy. For some countries, this monetary serfdom was tolerable because their industries were closely tied to Germany’s, and business conditions rose and fell in tandem. But some countries could not live with it. Britain had been forced to abandon its currency peg with Germany, in 1992, because it was in recession even as Germany enjoyed a boom. In the present day, China faces a related conundrum. It would like to open itself fully to capital flows in order to create a modern financial system, in which market forces play a bigger role. Last summer it took some small steps towards that end. But doing so at a time of sluggish economic growth raised fears that the yuan would dive. As markets panicked, China’s capital controls were swiftly tightened.

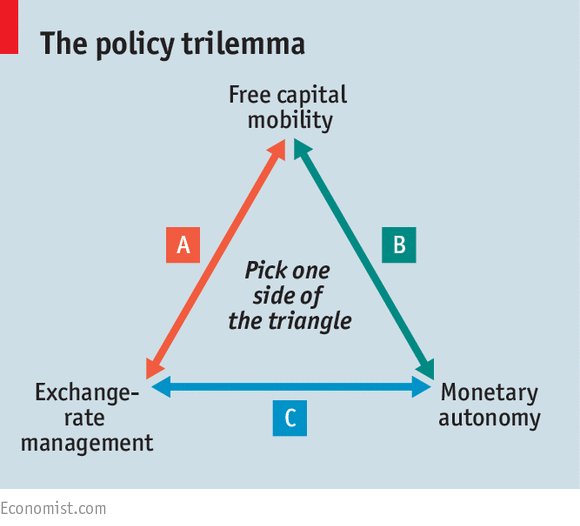

Both predicaments were a consequence of the macroeconomic policy

trilemma, also called the impossible trinity. It says a country must choose

between free capital mobility, exchange-rate management and an independent

monetary policy. Only two of the three are possible. A country that wishes to

fix the value of its currency and also have an interest-rate policy that is

free from outside influence cannot allow capital to flow freely across its

borders. That was China’s trilemma. If the exchange rate is fixed but the

country is open to cross-border capital flows, it cannot have an independent

monetary policy. That was Britain’s trilemma. And if a country chooses free

capital mobility and wants monetary autonomy, it has to allow its currency to

float. That is the two-from-three combination that most modern economies

choose.

Many emerging markets find that tying the exchange rate to a

stable monetary anchor, such as the dollar, can be useful. It is a speedy way

to show a serious intent to control inflation, for instance. Indeed this was also

the reason why Britain tied itself to the D-mark in the early 1990s. The cost

is a loss of monetary independence: interest-rate policy is subordinated to

maintaining the peg and so cannot be used flexibly to stabilise the economy.

That is why countries are generally advised to float their currencies once they

have demonstrated a commitment to low inflation. That way, the currency adjusts

to the waxing and waning of capital flows, allowing interest rates to respond

to the domestic business cycle. In practice, many emerging markets are fearful

of letting the exchange rate move sharply, so they choose to sacrifice either

free capital mobility (by introducing capital controls, or by adding to or

depleting their foreign-currency reserves) or monetary independence, by giving

priority to currency stability over other targets. China wants eventually to

liberalise its capital account as a stepping stone to a modern financial

system. To do so, it will have to live with a volatile yuan. Three out of three

ain’t possible, but two out of three ain’t bad.

Previously in this series

Monday: Akerlof’s

market for lemons

Tuesday: The Stolper-Samuelson theorem

Wednesday: The Nash equilibrium

Thursday: The Keynesian multiplier

Friday: Minsky’s financial cycle

Tuesday: The Stolper-Samuelson theorem

Wednesday: The Nash equilibrium

Thursday: The Keynesian multiplier

Friday: Minsky’s financial cycle

Over the past several weeks The Economist has

run two-page briefs on six

seminal economics ideas. Read the full brief on the macro-economic

policy trilemma, or

click here to download a

PDF containing all six of the articles.

Oh my God, this is too complex, too much text. Find something easier please, people.

ReplyDelete