ESSAY · ASIA'S SECOND-WORLD-WAR GHOSTS

The unquiet past

Seven decades on from the defeat of Japan, memories of war still divide East Asia

The Economist

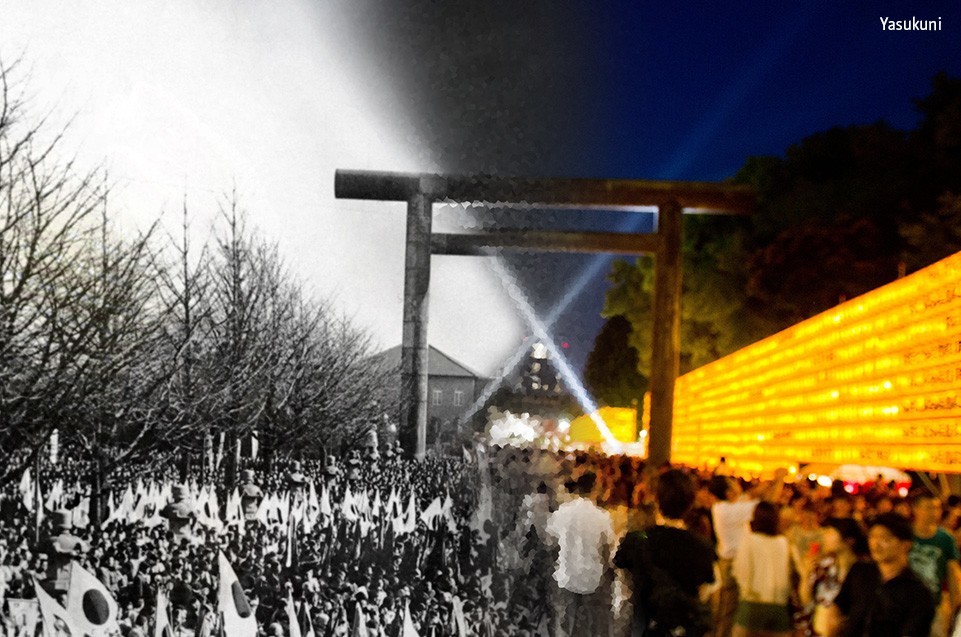

THERE can be no more pleasing spot in Tokyo on

a July evening than the Yasukuni shrine. The cicadas murmur as you pass along

the avenue of ginkgo trees framing the great shinmon gate, fashioned out of

dark balks of cypress. The chrysanthemum drapes of the worship hall flutter alluringly;

lanterns line the way, and the crowds are in a holiday mood and summer robes.

Parties chant with gusto as they parade past with the palanquins housing their

neighbourhood deities.

Yasukuni’s summer celebrations reach their climax on August

15th, the anniversary of Japan’s defeat in the second world war. As the date draws

closer the avenue expands into a Bartholomew Fair of stalls and revelry. Not

everyone is jolly. Sombre groups that include some of Japan’s few surviving war

veterans and their families remember fallen friends. There are chin-jutting

Yakuza thugs in suits a size too small, and strutting military fantasists

kitted out with officers’ swords or

And there are ghosts. Without them Yasukuni would have no

purpose. The shrine honours the souls of those who have died protecting the

emperor; they are revered as

The first

By the tenets of the shrine, all these spirits are equal. To the

world at large, they are not. No one objects to a nation honouring its war dead,

even if the cause for which they fought was a bad one. But in 1978 the priests

of Yasukuni surreptitiously enshrined 14 political and military leaders,

including General Hideki Tojo,

the wartime prime minister, who had been found guilty by the Tokyo War Crimes

Trial of planning or prosecuting the military aggression of the 1930s

and 1940s. All 14 had either been executed by Japan’s new American overlords or

died in prison. For many—including many in Japan—granting divine honour to such

men went beyond the pale. Emperor Hirohito, in whose name millions died, stopped visiting

Yasukuni; the current emperor, Akihito,

has upheld the boycott. Yet visits by conservative nationalist politicians,

including the prime minister, Shinzo Abe, have increased, drawing admonishment

in much of the world and stoking anger in China and South Korea.

There are other spirits that stand out, too—less infamous, but

more poignant. One is that of Lee Sa-hyon, who was a native of the city that

today is Seoul but from 1910 to 1945 was Keijo, the capital of

Japanese-occupied Korea. By the time Lee Sa-hyon was growing up in the 1930s,

most of his hometown’s city walls and royal palaces had been razed; there was

just enough left to make tour parties from Japan think that they were taking in

something exotic (Korean brothels were on the tourist trail, too). The huge

dome of the governor-general’s palace dominated the city centre. The Imperial

Subject Oath Tower, built for the celebrations in 1940 of the (wholly

fabricated) 2,600th anniversary of the Japanese imperial family, housed written

vows of loyalty to the emperor from 1.4m Korean students.

Lee Hee-ja, Lee Sa-hyon’s daughter, was born in 1943, a time

when Japan’s prospects were looking grave. The Americans were fighting their

way up through the country’s Pacific-island possessions. The war against China

that had begun in 1937, and which the Japanese had expected to be a relatively

short affair, had developed into a long struggle on an epic scale thanks to the

resistance of the ascetic Christian generalissimo, Chiang Kai-shek, and his

Kuomintang (KMT). The demands of the war effort stripped Korea and occupied

Manchuria to its north of both resources and people. Thousands of Korean women

were tricked and abducted into military brothels; tens of thousands of men were

forced into labour in mines and on industrial sites, mainly in Japan. And from 1944

many were conscripted into the army. Lee Sa-hyon became one of those

conscripts. In June 1945, just a few weeks before the war’s end, he was killed

in Guangdong, in southern China.

His daughter is now 72. Like all East Asian septuagenarians she

has lived through times of startling disruption. Like China, Ms Lee’s country

was wracked by civil war and divided into two; like Japan and Taiwan, and later

China itself, it was also transformed by remarkable economic growth. Its

population has tripled, its GDP risen by a factor of 50. It has become, for the

first time in its history, a democracy. From the far end of a lifetime of such

profound change the war might be expected to seem distant—as it does, for the

most part, in America and Europe. But in ways both great and small, in the

details of individual lives and in the relations between states, the war that

ended 70 years ago still shapes East Asian worldviews, animating its

politics—and its ghosts.

In 1959 the spirit of Lee Sa-hyon was quietly enshrined at Yasukuni;

having died fighting for the emperor, he became one of his divine protectors.

When his daughter found this out, in 1996, she became determined to have his

name, and

Moving a soul in Japan proves to be not so easy. Yasukuni’s

priests were polite but firm. Once a spirit has joined the

Along with others eager to liberate relatives from

Yasukuni—including some Japanese—Ms Lee has turned to the courts. They have

offered no joy. In the latest set of cases, one of the names for removal is

that of an elderly plaintiff, the reports of whose death have clearly been

exaggerated—yet even being alive, it seems, does not get you struck from the

list of the

Why, Ms Lee asks, does Japan’s establishment not understand the

humiliation of families like hers, one it would be so easy to redress? Japanese

prime ministers have apologised for their country’s aggression; its government

has acknowledged its culpability in enslaving women in brothels. And the

Japanese know what it is to have people taken from them. Mr Abe made his

political reputation when, more than a decade ago, he stood up to North Korea

over a number of Japanese citizens kidnapped in the 1970s and 1980s to serve

the brutal regime as translators and spies. Every day Mr Abe wears a blue

ribbon in his lapel as a reminder of them. Can he not see, Ms Lee says, that

her father was abducted too?

But no name has ever been removed from Yasukuni.

The Meiji

Restoration initiated a bout

of modernisation the like of which the world has never seen elsewhere. Not even China’s transformation

since 1978 compares to it. In less than two generations an insular feudal

shogunate became a modern power—not just an

economic power, but a military one. Japan’s leaders never forgot the indignity

of American gunships forcing open what Herman Melville called their

“double-bolted land”. Fukoku

kyohei, went the rallying cry: “rich country, strong army”.

In the 70 years since 1945 Japan has fired not a

bullet in anger. In the 70 years before that, war was central to its progress. Its

expansionism began in 1874, when it launched a first punitive expedition to

Formosa (now Taiwan). In 1879 it annexed the peaceful Ryukyu kingdom—modern-day

Okinawa. A war against the Qing dynasty in 1894-95, fought largely on the

Korean peninsula, ended in humiliating defeat for China; its centuries-old

dominance of East Asia was usurped. In 1905, in the greatest naval victory

since Nelson’s at Trafalgar 100 years before, Japan sent nearly the entire

Russian fleet to the bottom in the Tsushima Strait between Korea and Japan,

setting the scene for its subsequent uncontested annexation of Korea.

Given the condemnation Japanese militarism was later to receive,

it is worth recalling the admiration Japan’s military modernisation inspired in

these early decades. It dressed its imperial adventures abroad in a cloak of

righteousness, legalism and brute force—just as Western imperial powers did.

Impressed, those Western powers could hardly deny their pupil a place at the

top table—even if the new member of the club was quick to detect racist slights.

Asian nationalists, too, admired this new Japan—among them Sun

Yat-sen, the future founder of republican China. Radicals and intellectuals

flocked to Tokyo to learn from an Asian power that could foster pride and

prosperity at home while standing up to the West abroad. The admiration even

extended to Yasukuni, embodying as it did the virtues of loyalty,

self-sacrifice and patriotism. In the early 1890s Wang Tao, a Chinese

intellectual and reformer, wrote approvingly that it was “easy to understand

the intention behind the Japanese government’s enshrining of the war dead: the

enthusiasm of the masses will flourish, and their loyalty will never be found

wanting.” Imperial China’s defeat at Japanese hands followed shortly thereafter.

Like the imperialism of the European powers it sought to emulate,

Japan’s colonialism was rooted in violence and, often, racism. But by

the early 1930s it had also become oddly chaotic—the result not so much of a

strategic aim to further national greatness as of a lack of control over

adventurism. The last of the oligarchs who had wielded power after the Meiji

Restoration, and who had a restraining influence on the armed forces, shuffled

off the stage. In 1931 a clique of army officers presented their occupation of

Manchuria to the government as a fait accompli. After the League of Nations

condemned the move, Japan withdrew from the body and entered a pact with Nazi

Germany in the name of fighting communism. In 1937 a flare-up between Chinese

and Japanese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge outside Beijing precipitated a

“war of annihilation”, as Japan’s prime minister, Fumimaro Konoe, called it,

down the length of China’s eastern seaboard.

Many conservative Japanese nationalists still see the beauty of

that period. Mr Abe believes that Japan’s pursuit of

To take such a position is not to deny that Japan did wrong.

John Delury, a historian of East Asia at Yonsei University in Seoul, argues

that, instead, it is to believe that imperial Japan behaved in war little

differently from other countries. And other countries did grievous wrong.

Witness the smouldering aftermath of the firebombing of Tokyo, in which 100,000

died; witness the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On this view

history places no special obligation of remorse or apology on the Japanese:

“indeed, not feeling obliged to express special remorse…is a manifestation of

Japan’s belated return to normalcy”.

Back at Yasukuni, the shrine is bathed in beautiful lies. A

visit to its associated museum, the Yushukan, finds the militarism that brought

Japan to its knees still glorified. Grim engines of death have pride of place,

including the

When Mr Abe paid his respects at Yasukuni in late 2013 he

fulfilled a campaign promise and generated a diplomatic storm. Around the world

China’s diplomats took to op-ed pages with the aim of stoking anti-Japan

sentiment. In Britain’s Daily

Telegraph the

Chinese ambassador to London, Liu Xiaoming, called Yasukuni a “kind of horcrux,

representing the darkest parts of [Japan’s] soul”. He expected his readers to

know that, in the world of Harry Potter, a horcrux stores a fragment of a

sundered soul in hope of immortality, and can be created only by murder. He

hoped they would infer that Mr Abe was the new Lord Voldemort.

It was a smart stroke of rhetoric. It was also more than a

little disingenuous. China’s Communist Party has a horcrux of its own on which

until not long ago it pinned all hopes of immortality—the corpse of Mao Zedong.

His violent rule saw the murder in purge and famine of millions of his

countrymen. Yet since his death in 1976 his remains have lodged under a huge

and ugly mausoleum in Tiananmen Square, the symbolic centre of Chinese power,

embalmed but very slowly putrefying.

Mao is a necessary source of legitimacy for China’s rulers, but

no longer a sufficient one. There is enough awareness of the violence and

misrule that he oversaw that even the Communist Party has had to avow that his

rule was only “70% good”. And as China’s economic and diplomatic clout grow,

prestige matters to its rulers in ways that never really interested Mao, and

which his legacy can do nothing to promote. So a reinvigorated nationalism has

joined economic growth and military strength as part of the “Chinese Dream”—a

nationalism defined above all in opposition to wartime Japanese aggression.

President Xi Jinping clearly sees the memory of that struggle as a tool for

shaping Chinese identity.

China’s leaders think memories of its role in the war should matter

abroad, too. America’s claim to a Pacific presence rests on its defeat of

Japan. China’s claim to leadership in its region rests on its role in that same

defeat—a role for which, after all, it was at the time rewarded with one of the

permanent seats on the UN Security Council reserved for the victors. In Mr

Liu’s horcrux op-ed he referred to Chinese soldiers standing “shoulder to

shoulder” with Allied troops. Last month he sent this correspondent an

invitation to a 70th anniversary commemoration of August 15th that refers to

“the Victory of the World Anti-Fascist War and the Chinese People’s War against

Japanese Aggression”.

China’s contribution to the second world war certainly deserves

a reappraisal, as Rana Mitter of the University of Oxford argues in a recent

book on the Sino-Japanese war, “Forgotten Ally”. From the outbreak of

hostilities at the Marco Polo Bridge in 1937 to December 7th 1941, when Japan’s

attack on Pearl Harbor forced America into the war, China fought Japan alone.

Mr Mitter argues that, had China surrendered in 1938, as seemed all too likely

at the time, East Asia might have been a Japanese imperium for decades. Instead

it fought on, at enormous cost. Perhaps 15m Chinese soldiers and civilians died

in the war of 1937-45, with 100m made refugees; of the other nations at war

only the Soviet Union suffered losses on a similar scale. True, China failed in

the end to beat the Japanese. But its dogged resistance tied down hundreds of

thousands of Japanese troops.

This is the legacy that Mr Xi insists be recognised. But there

is an inconvenient truth. For decades the official Communist Party narrative

had little space for the KMT and Chiang Kai-shek; if they were mentioned at

all, it was as anti-communist forces too cowardly, corrupt or unpatriotic to

take on the Japanese. China’s “liberation” came not in 1945 but in 1949—that

is, with the Communists’ defeat of the nationalists in the civil war that

followed Japan’s collapse. Communism’s victory over nationalism was thus framed

as the end point of its victory over fascism.

Yet it was in fact the armies of the anti-imperialist, fiercely

nationalist KMT that offered the chief resistance to Japan’s army, drawing it

ever deeper into the mire. It was they who shared in the suffering, hardship and

endurance on the part of hundreds of millions of Chinese civilians that marked

the eight wartime years beyond the relatively small and secure Communist base

areas. It is quite possible that, had the KMT not spent so much of its force in

that struggle, Chiang would have won the subsequent civil war.

Viciously suppressed in the decades following the war, this part

of the country’s history is now being cautiously and selectively rehabilitated

as part of the new nationalism through which China is expressing its regional

and global aspirations. Among other things, this serves the purpose of uniting

the stories of Taiwan—to which Chiang and the KMT fled in 1949—and mainland

China, stressing the common struggle of the Chinese against Japanese aggression

rather than their division by civil war. Beyond reasons of state, though, it is

also bubbling up from below, as regions of China previously marginalised

manifest a new desire to tell their own war stories.

In a large apartment in a brand-new suburb of Chongqing, a city

in China’s south-west, Wang Suzhen, a diminutive lady in floral pyjamas,

disappears into a vast faux-leather sofa surrounded by three generations of her

family. Opposite, a television covering the entire wall pumps out a reality

programme devoted to parental indulgence: a father takes a girl in a tutu to a

ballet lesson; a little emperor in sunglasses drives a scale model of a BMW.

Outside, Chongqing is Dickensian in its smog and nearly hellish in its summer

heat, the Yangzi river winding brown and swollen at the feet of its steep

hillsides.

Chiang Kai-shek retreated to Chongqing with his government in

1938, the year after Nanjing, then the capital of the Republic of China, fell

to the Japanese amid great slaughter—an infamous victory which put the invaders

in control of nearly all of China’s coast, including Shanghai. Millions of

Chinese followed Chiang to Chongqing; it was the provisional capital until the

end of the war.

They were seven hard years. Though geographical remoteness and

mountain topography offered the city a degree of protection, the war was always

present. Many civilians died in air raids; on June 5th 1941 some 1,500

civilians died from suffocation in a single shelter. Boatmen were paid half a

kilo of rice per body to take the corpses out of the city.

The Wang family did better than most. Living outside Chongqing

in a town called Shilong, they escaped the air raids. Just six days before the

defeat of Japan, Ms Wang was born. Soon after the family moved to Chongqing

proper where they made a living selling the silk embroidery they made in the

city’s wholesale markets. But the Communist victory in the civil war changed

the city. Chongqing’s sense of itself as a centre of resistance, and its price

in its wartime experience, were suppressed. Its Monument to Victory in the

Anti-Japanese War was renamed the Liberation Monument. People with a “bad”

class background—that is, evil “landlords” and nationalists who had come to the

region with Chiang Kai-shek—were stigmatised. Ms Wang’s family was forced out

of the city and into the countryside.

One political campaign after another washed over the

agricultural collective where Ms Wang’s mother struggled to feed eight

children. Ms Wang remembers a cow being brought to the production team in

winter, but having no hay with which to feed it. Then people started eating

grass themselves, leading to bloating and sometimes starving all the same.

Later, during the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards dragged evil “landlords”

outside and beat them. “We didn’t ask questions,” Ms Wang says. “We didn’t dare

speak, or we’d get beaten too.”

In 1987 Ms Wang and her family left the commune and prospered

growing their own crops for market. The government gave her daughter, a

teacher, a flat, into which they all moved. In 1989 they got their first

television, and a fridge. In 2005 they bought their first car. No one in the

family imagined that things could change so fast. A few years ago Ms Wang found

spiritual comfort, too. It happened when an elderly relative died, leaving

behind her troubled ghost. A Taoist master was called in to appease the ghost

but it did not work. “Then some Christian friends said that their kind of

prayers could bring peace, and they did.” The ghost no longer troubles the

family; Ms Wang goes to church each week.

In her spiritual development Ms Wang is somewhat unusual; in her

family’s enrichment she is quite typical of her city. And as the south-west has

grown richer, so it has started to tell the story of its wartime experience

more openly. On August 15th Chongqing’s newspapers used to spout the same

national narrative one might read in Beijing. Now they celebrate local wartime

heroes. The air-raid shelter that suffered the disaster of 1941 has been

designated as a memorial site. In Chiang Kai-shek’s hilltop hideout of

Huangshan visitors are welcomed by a young actor decked out in the

generalissimo’s scholarly gown and thin moustache.

If Chongqing is reclaiming its past—and China as a whole coming

to acknowledge the role of nationalism, and not just communism, in fighting the

forces of imperialism—what does that mean for relations with the Japanese?

There are signs it may improve them; a more nuanced view of Chinese history

permits a more nuanced view of its adversary.

On the face of it, Ms Wang still sees things the old way: the

Japanese, she says, are cruel and she dislikes them. Has she ever met one? No,

she admits, but—nodding at the television—she sees them all the time. Reminded

that the Japanese in the war movies on television are Chinese actors in

costume, she laughs. “It’s just propaganda, I know,” she says, before becoming

absorbed along with the rest of the family in the girl in the pink tutu.

Mr Xi’s use of old antagonisms to buttress a modern nationalist

identity is a worrying one. But there is a lot else shaping the ideas of a richer

society than any China has known. As if to underline the point Ms Wang murmurs,

as much to herself as to this correspondent, “Who would miss the past?”

The spirits of Yasukuni are not the only ones with whom Mr Abe

communes. After his election victory in 2012 he went straight to the tomb of

his grandfather to make a promise. Like his grandson, Nobusuke Kishi rose to be

prime minister, serving from 1957 to 1960. A fervent nationalist, he had

nonetheless accepted, in the face of Japan’s surrender to the United States and

its neutered post-war role as little brother, that the restoration of wealth

had to come before the resumption of power. But—and Kishi was clear on this

point—this was to be only a temporary expedient.

In 1965 Kishi argued that rearmament was necessary as “a means

of eradicating completely the consequences of Japan’s defeat and the American

occupation. It is necessary to enable Japan finally to move out of the post-war

era and for the Japanese people to regain their self-confidence and pride as

Japanese.” The words could have come from Mr Abe’s manifesto. The promise Mr

Abe made by his grandfather’s grave was that he would “recover the true

independence” of Japan.

This is not to say that Mr Abe is anti-American. Like his

grandfather, he needs America to ensure his country’s security. He has

strengthened the countries’ military alliance, agreeing to revised defence

guidelines in April in the face of a rising China. But he feels deeply

America’s role in “the history of Japan’s destruction”—by which he means not

the physical devastation of the war, but the subsequent period of

American-imposed order. He hates the war-crimes tribunal that sat in Tokyo:

what hypocrisy to hang the Japanese leaders who conquered Asia at the same time

as the Western powers were reasserting their rule in Asian colonies. He sees

the constitution imposed on the country as constraining Japan’s legitimate

ambitions. A left-wing conspiracy in education inculcates war guilt and an

aversion to patriotism.

The role of that post-war order in the subsequent seven decades

of peace, prosperity and democracy from which Mr Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party

has been a great beneficiary is passed over in such analysis. Yet America is in

no position to call Japan’s nationalists out on the grounds of double

standards. It was, after all, General Douglas MacArthur who chose not to

prosecute Emperor Hirohito for the crimes that were committed in his name and

by a political system to which he was central, on the unprovable but

implausible grounds that a crushed people would be more biddable with their

emperor still in place. That decision made it harder for Japan to examine its

actions, and make a full accounting of them, both to its victims and to itself.

The cold war, for which America needed experienced, conservative allies in

Japan, removed any lingering chance of such a reckoning. Almost immediately

after the Tokyo tribunal handed down its first batch of sentences, the other

people indicted for Class A crimes were released from Tokyo’s Sugamo prison and

put in positions of authority.

Notable among them was the mastermind of Japan’s Manchurian

puppet state, known as Manchukuo, in north-east China. By harnessing private

capital to a heavily state-directed economy, he had turned Manchukuo into the

engine of Japan’s war machine. Mark Driscoll of the University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill has written of the system’s “necropolitical” vision of

dehumanised Chinese labour. Yet the brutal human cost of this experimental,

hyper-modern state is now largely forgotten, while its marriage of private

capital and heavy state direction was a direct inspiration not just for Japan’s

post-war development, but also, subsequently, for that of South Korea—and

China, too. And the mastermind behind this? Nobusuke Kishi himself.

Mr Abe’s

uncritical belief that his country’s essence is inextricably bound into the

institutions of the Meiji

Restoration and all that they

went on to spawn is wrongheaded. But

it is equally wrong to decry all aspects of continuity between Japan’s pre-war

and post-war. On all sides ghosts are kept locked away. Instead they should be

allowed to speak and also to listen—to hear and voice the complex truths of

war, responsibility and victimhood.

Xu Ming remembers the first time she found herself outside

without her mother holding her hand. She asked a group of children if she could

play. “ ‘No’, said one. ‘Why not?’ I asked. ‘Because you’re a

Ms Xu was born in Heilongjiang province in north-east China,

part of Manchuria, in 1944—three years after Kishi had been recalled from his

position there to serve as industry minister in Tokyo. She was an only child

brought up by loving and protective parents. And she was badly bullied. When

she was seven her class were taken to see a war film that showed Communist troops

in glorious battle against the murderous, evil Japanese. The children around

her starting shouting “Down with the Japanese”. And then they were spitting at

her. After the film the teacher held a roll call, but Xu Ming was missing. The

teacher found her crouched under her chair, her eyes red with crying. She

scolded the class: Xu Ming, she said, is only a child; and the film is only a

film. That day, Xu Ming determined to be a teacher.

A year later an officer from the Public Security Bureau came to

her house. Xu Ming was sent outside but craned to hear the conversation. The

officer was shouting: “You had better admit it: the child is Japanese and you

adopted her.” Her mother burst into tears. Xu Ming ran in to comfort her.

Mother and daughter cried so much that the officer gave up any further

questioning.

It was then that Xu Ming asked: “I’m Japanese, aren’t I?”

“Yes”, her mother replied, “you are.”

According to John Dower, there were over 6m Japanese stranded

overseas when the war ended. Their story is strangely little told, even in

Japan. Something over half of the stranded were servicemen, many wounded,

malnourished or diseased. The rest were administrators, bank clerks,

railwaymen, farmers, industrialists, prostitutes, spies, photographers,

barbers, children. For them and for their families and friends back home, just

as for conscripted and exiled Chinese and Koreans in similar situations, August

15th was far from a definitive end. A year after its defeat 2m Japanese had

still not made it home. Many never did. A national radio programme, “Missing

Persons”, was launched in 1946. It went off-air only in 1962.

The Allies took advantage of surrendered servicemen. The

Americans used 70,000 as labourers on Pacific bases. The British, in a supreme

irony, made use of over 100,000 Japanese to reassert colonial authority over

parts of South-East Asia that had just been “liberated”. In China tens of

thousands of Japanese fought on both sides of the civil war.

The worst fate was to be under Russian “protection”. The Soviet

Union, which entered the war in its last week, accepted the surrender of

Japanese forces in Manchuria and northern Korea. Perhaps 1.6m Japanese soldiers

fell into its hands. About 625,000 were repatriated at the end of 1947, many

having been sent to labour camps in Siberia and submitted to intense

ideological indoctrination. Others were able to make their way south to the

American-controlled sector of the Korean Peninsula. In early 1949 the Soviets

claimed that only 95,000 Japanese remained to be repatriated—leaving, by

Japanese and American calculations, over 300,000 unaccounted for.

In August 1945 there were also 1m Japanese civilians in Manchuria.

Some 179,000 are thought to have died trying to get to Japan in the confusion

and Soviet-perpetrated violence following surrender, or during the harsh winter

of 1945-46. Children returned to Japan as orphans, the family’s ashes in a box

hung around their neck. In Manchuria parents begged Chinese peasant families to

take in their youngest children.

That is what Ms Xu’s natural mother had done. Her father,

serving in the imperial army, had been dragged off to Siberia. Her mother

thought Ming, the youngest of her daughters, would not survive the journey to

Japan. She begged a couple to take the baby. When that couple later had more

children of their own they sold Ming on to the Xu family.

In due course Ms Xu passed as a teacher. She qualified with flying

colours that might have hinted at a stellar career. But the following years

were spent teaching the children of loggers in dismal mobile camps deep in

Heilongjiang’s forests. “There’s nothing you can do about it,” her professor

had said: “You’re Japanese.” In the timber camps they ground up sweetcorn husks

and tree bark for bread, but living in such remote places shielded Ms Xu from

the worst madness of the Cultural Revolution. Back in her home town the

ethnic-Japanese dentist, gentle and diligent, was dragged to the crossroad with

a sign around her neck denouncing her as a Japanese spy. Every time she was

asked whether she was a spy and denied it she was hit. Three days later she was

dead.

In 1972 the Japanese prime minister, Kakuei Tanaka, visited China,

initiating a programme of billions of dollars of bilateral aid for its former

foe. Japanese people started coming to Heilongjiang to look for family members.

A visiting journalist promised Ms Xu he would place advertisements on her

behalf in Japanese publications so that she might find her birth family. An old

soldier in Hokkaido responded to one, certain she was his daughter. In 1981 a

visa was secured for Ms Xu. She was intensely excited to go to Japan; her

meeting with the old soldier was emotional. Then a DNA test showed they were

not related. The old soldier would have no more to do with her.

Japanese bureaucrats threatened to deport Ms Xu: Chinese court

documents affirming her Japanese blood counted for nothing. While fighting

through the courts to stay, she volunteered her help at a local NGO dealing

with the “Manchurian orphans”. One morning, in a nearby café, two Japanese

women on the way to the NGO asked whether they could share her table. Of

course, Xu Ming said, in her still accented Japanese. The women asked whether

she was Chinese and if so from where? Heilongjiang, Xu Ming replied. That’s

where our mother left our sister, the women said. The coincidences grew: the

town, the name of the family, Li, that first adopted Ms Xu, the Li home being

right by the railway track. The three sisters were together again for the first

time since 1945. For Sumie Ikeda, as Ms Xu now knew herself to be, the elation

was tempered only by her learning that their mother had died just months

before. But now her ghost, at least, could rest.

The lives scarred in the second world war are nearing their

ends. The Asian history they are part of continues to shape the worlds of those

people’s children and grandchildren, though. In some places it is distorted, in

others denied. Some victims and some victors are commemorated. Others are

forgotten.

In the 1960s a head priest at Yasukuni more liberal than today’s

put up a tiny shrine in a corner of the grounds to pacify the spirits of fallen

enemies. It is now surrounded by a high metal fence, and out of bounds to

visitors. On its annual feast day in July a young priest unceremoniously places

a bowl of fruit outside the shrine as an offering and shambles off. As for the

Japanese victims of aggression—the young soldiers, let down by their generals,

who died of hunger and disease in New Guinea jungles, the hundreds of thousands

of civilians killed as the war came to the Japanese home islands: they are

nowhere to be seen. Yasukuni remembers only glorious deaths.

“Who would miss the past,” asks Ms Wang, from her sofa in

Chongqing. Who indeed? But the past is not just there to be missed.

No comments:

Post a Comment