|

| Richard Dudman (far left), Malcolm Caldwell (far right), the author, and Commander Pin, a senior Khmer Rouge military figure, stand near Cambodia's eastern border. (Courtesy of Elizabeth Becker) |

Reporting massive human rights abuses behind a façade

Two reporters escaped with their lives, but left Cambodia with very different stories. History shows one was right.

Last year, I

was flown to Cambodia to testify as an expert witness for the

prosecution at the genocide trial of two senior Khmer Rouge leaders. As a

journalist and author, I assumed my biggest challenge would be

protecting any confidential sources while maintaining a reporter’s right

to refuse to testify. I consulted an attorney and assured myself on

both counts. Then I pored over documents and interview transcripts,

preparing for tough questioning from the defense.

I testified for three long days in a somber courtroom in Phnom Penh. I

repeatedly insisted that the defense attorneys explain each flimsy

allegation before I answered their questions, and spoke slowly to insure

I didn’t make any foolish mistakes. I held back tears discussing the

assassination of a British professor I’d witnessed in 1978.

The United States had called the continuing Cambodian tribunal the

most important human rights trial in the world today. At the trial I

attended, the last two surviving Khmer Rouge leaders, Nuon Chea and

Khieu Samphan, were finally being held accountable for their role in the

radical and savage revolution that killed over two million Cambodians—a

quarter of the population—between 1975 and 1979.

Yet despite all my preparations, there was one big surprise: The

trial inadvertently resolved a 37-year-old disagreement between two

reporters over how to cover genocide. Fundamentally, it was a classic

clash of reporting styles. I was a young journalist who had learned

about Cambodia’s culture, history, politics, and language and, above

all, had lived with its people. My colleague and competitor was a senior

reporter based in Washington with deep experience covering the State

Department and US foreign policy who visited or parachuted into many

foreign countries to cover world events, but who had not lived in

Cambodia.

While our story is from another era, its basic thesis is timeless.

Genocide is only obvious in hindsight. When a regime is murdering its

people, it is close to impossible to find real-time evidence of

atrocities. Instead, reporters must navigate strong-arm propaganda and

outright lies to uncover the truth behind charges of gross human rights

violations. Critics, power brokers, and even colleagues in the press

will deny the findings. But it is a reporter’s responsibility to get

answers.

The author sits outside a temple at Angkor Wat

with Richard Dudman (front right), Malcolm Caldwell (back left), two

young aides, and Thiounn Prasith, a senior Khmer Rouge official at the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (Courtesy of Elizabeth Becker)

My testimony had been highly anticipated because I was one of only

two Western journalists ever allowed to report from Cambodia under the

Khmer Rouge, and one of the first reporters to

interview Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge leader who has been called the Hitler

of Cambodia. The other was my aforementioned senior colleague, Richard

Dudman of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

I had gone to Cambodia for the first time in late 1972, abandoning a

graduate program in South Asian studies to report on the last country to

become part of America’s Vietnam War. I quickly became the local

correspondent for The Washington Post, a rare opportunity for a

woman at the time. For two years—1973 and 1974—I lived in Cambodia and

lived through the war. I got to know the country fairly well, traveling

widely, relying on Cambodian friends, and learning to speak some of the

Cambodian language.

Afterwards, I joined the Post staff in Washington, but never

forgot Cambodia. And in December 1978, I got a rare opportunity to

return. The only news about Cambodia at that time came

from official broadcasts or refugees who managed to escape. Under the

radical communist Khmer Rouge, Cambodia had isolated itself more

thoroughly than any other nation on the planet, including North Korea.

Refugees told harrowing stories of mass starvation, labor camps, and

arbitrary executions, describing the country as a living hell. But those

were the stories of Cambodians who had fled. No defectors had made it

out to the West, and no reporter had gotten inside. Were those stories

true?

The Cambodian government invited three outsiders to tell the country’s story: Dudman of the Post-Dispatch;

Malcolm Caldwell, a British professor specializing in Southeast Asia;

and me. The regime had let us in because it had ignited a border war

with its former ally Vietnam, and Cambodian leaders wanted international

help blocking a pending Vietnamese invasion.

While our story is from another era, its basic thesis is timeless. Genocide is only obvious in hindsight.

As soon as we arrived, it was clear that we would have no freedom of

movement. Instead, our visit was the equivalent of a guided tour under

armed guard. We would only see what the Khmer Rouge wanted us to see.

This was the same strategy the German Nazis had used when they

allowed the International and Danish Red Cross to visit their

Theresienstadt camp ghetto in Czechoslovakia during World War II—one of

the rare Red Cross inspections of any Nazi camp. The Nazis tidied up

Theresienstadt by painting barracks, planting gardens, and organizing

musician prisoners to entertain the visitors. The Red Cross delegation

was taken in, reporting back to the Danish government

that the camp had comfortable housing and a rich cultural life,

including a library and social club with its own orchestra. After the

Red Cross visit, the camp resumed its inhumane work of transporting

victims to their deaths in Auschwitz and other concentration camps.

Dudman and I had the same responsibility as those Red Cross workers

to discern the existence of a possible genocide behind the official

façade.

Documenting genocide is a staggering responsibility at any time, and

an especially difficult one for us in 1978, when the world was still

locked in the Cold War. The competition between the United States and

the Soviet Union had essentially neutralized any internationally

approved investigation of mass atrocities or genocide. The Nuremberg

trials of alleged Nazi war criminals in the late 1940s were the last

prosecution for genocide—the last time the two superpowers could agree

on a trial. We knew that no matter what we discovered, it was highly

unlikely that the UN or any other international body would call for the

arrest and trial of the Khmer Rouge.

Dudman, Caldwell, and I spent nearly every minute of

the two-week trip together. The totalitarian regime set up a tight

schedule, deciding where we would go, whom we would see and talk to, and

what propaganda point would be made at each stop. At night, we were

locked inside guest houses.

What I saw when I returned to Phnom Penh was a

capital city emptied of people….It was a shock and a nightmare to see

the city transformed into a near-ghost town.

In theory, we should have come to similar if not identical

conclusions. Yet Dudman and I perceived Cambodia very differently. A

senior diplomatic correspondent at the time, Dudman wrote his stories

based on a previous trip to the country, his readings about Cambodia,

and exactly what he saw during our visit. After two weeks in the

country, he came to the conclusion that he had seen “a generally healthy

population,” and that the people were “clearly not being worked to

death and starved to death.”

“Physical life may have improved for peasants and former urban

workers, possibly for the vast majority of the population,” he wrote in

the St. Louis Post-Dispatch upon our return.

My reporting was based on the same two weeks’ experience, but in the context of what I knew was missing. The Cambodian society I’d gotten to know in the early ’70s was

still vibrant, even in the midst of war. The Cambodians I met were

generous, welcoming family and friends uprooted by the fighting into

their increasingly crowded homes. The arts still thrived, from Cambodian

movies and rock and roll to the traditional ballet that evokes the

majestic art of the temple complex at Angkor. If anything, Cambodians in

that period had been too naïve, failing to understand how joining the

American-led Vietnam War in 1970, including the massive 1973 American

bombing campaign of Cambodia, would contribute to their nation’s defeat

and the nightmare of the Khmer Rouge a few years later.

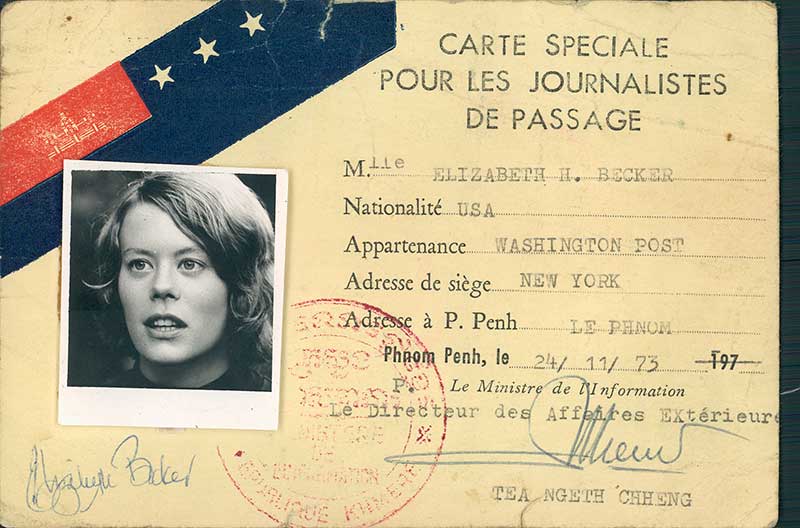

The author’s press card from 1973 (Courtesy of Elizabeth Becker)

What I saw when I returned to Phnom Penh was a capital city emptied

of people. I had read the reports from refugees that said Cambodians had

been force-marched out of the towns and cities to the countryside,

where they lived in communal camps, worked in labor gangs, ate in

canteens, and had no private lives. They also said that hundreds of

thousands had simply been killed. Still, it was a shock and a nightmare

to see the city transformed into a near-ghost town.

In Phnom Penh, we only saw people when we were driven to model

clinics, political headquarters, or staged events. We were told that

workers occupied some buildings, but there was no semblance of normal

life. I snuck out twice from the guest house during our siesta hour and

saw blocks of abandoned buildings left to rot. On the first of these

forays, I ran into a group of workers in black pajamas who let me take

their photograph and then disappeared into a building. They seemed

almost afraid of me. The second time, I was caught. After that, the

guesthouses were locked during the day as well as at night.

All of the schools appeared to be shut down, so I asked where the

children were studying. Our high-ranking guide said they were learning

in the countryside. Pagodas, mosques, and churches were shuttered. All

commercial life was forbidden: There were no more markets, no stores, no

banks, no cafés. The old art-deco Central Market where farmers and

artisans once sold their wares was empty, and the land around it had

been planted with banana trees. There was no music, no

dancing, no movie theatres, no Cambodian soup or noodle vendors—none of

the daily Cambodian joie de vivre that had survived the war but

not this revolution. It occurred to me that this was how extreme

communism looked when the government owned everything and controlled all

aspects of life.

There was no music, no dancing, no movie

theatres, no Cambodian soup or noodle vendors—none of the daily

Cambodian joie de vivre that had survived the war but not this

revolution.

The curtain lifted only once, during a road trip to an agricultural

region. We were standing at an empty highway rest stop when, across the

road, I saw a single-file line of thin children, barefoot and in rags,

carrying light firewood. I grabbed my camera and took a few photographs

while our guide explained that these children were “students” learning

about farming.

I wanted to give the Khmer Rouge a chance to disprove the stories of

wholesale slaughter and deprivation. I asked my minders to let me

interview someone I might have known when I lived in Phnom Penh—someone

who could tell me that he or she was doing OK. Our guide refused. “You

will never understand Cambodia,” he told me. (Documents retrieved after

the fall of the Khmer Rouge revealed that my questions convinced them I

was a CIA agent.)

Then we ourselves became targets of the regime. On our last day,

Dudman and I interviewed Pol Pot for two hours. Immediately afterwards,

Caldwell, the professor, had a separate interview with him. We were all

relieved that the long, extremely difficult and nerve-wracking trip was

coming to a close, and we went to sleep just before midnight. But an

hour later, a Cambodian assassin attacked us in our guesthouse. I

heard a crash and ran from my bedroom to the living room, coming face

to face with a gunman who pointed his pistol at me. I ran and hid in a

bathtub while the assassin raced upstairs, where he saw Dudman, who ran

into his room and locked the door. Then I heard the sickening sound of

repeated gunshots, followed by silence.

I waited by myself in the dark for several fearful hours before we

were rescued. Dudman was safe, I was told, but Caldwell had been

murdered. The Khmer Rouge foreign minister blamed the Vietnamese for

Caldwell’s murder. Still traumatized, I said, no, the gunman was

Cambodian. I knew a regime that controlled our every move could have

protected us from that assassin. I had to conclude that they wanted

Caldwell dead, and to frighten Dudman and me. (Years later, a scholar

found documents in the Khmer Rouge archives showing that several

low-level Khmer Rouge figures were tortured and executed for killing

Caldwell.)

I heard a crash and ran from my bedroom to the

living room, coming face to face with a gunman who pointed his pistol

at me. I ran and hid in a bathtub while the assassin raced upstairs,

where he saw Dudman, who ran into his room and locked the door.

Writing in the Post-Dispatch, Dudman reported that the

“information received in advance [from refugees] was mostly misleading,”

and that he had found a “healthy demographic mix of men, women and

babies.”

He also wrote that under communism, Cambodia had become “one huge

work camp, but its people clearly were not being worked to death or

starved to death.” He won several prestigious awards for his work,

including the Weintal Prize for diplomatic reporting and a George Polk

Award following his 1990 New York Times essay insisting that Pol Pot may have been brutal, but was no mass murderer.

Meanwhile, I wrote that I believed the regime was guilty of committing gross human rights abuses in a series for The Washington Post, describing all that we’d seen and not seen. For my efforts, I won an honorable mention from the Overseas Press Club.

It was a standoff. The Khmer Rouge had the sympathies of some

American activists still incensed over the Vietnam War. Noam Chomsky

dismissed my work and said Dudman was the more reliable reporter.

Incredibly, even the US government took Dudman’s side. The Vietnamese

invaded Cambodia and overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979, opening up a

treasure trove of documents and horrific evidence that implicated the

regime in far worse crimes than anyone had imagined. But after

condemning the Khmer Rouge while Pol Pot was in power, the US did an

about-face and supported the Khmer Rouge in exile.

An empty Central Market looms in the background

in Phnom Penh, 1978, when the city had effectively become a ghost town.

(Courtesy of Elizabeth Becker)

Embittered by the outcome of the Vietnam War and taking the side of

China against the Soviet Union in the great communist split, Presidents

Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush decided that

Vietnam’s defeat of the Khmer Rouge and occupation of Cambodia was the

real problem. The US refused to even discuss the massive human rights

abuses under the Khmer Rouge, instead treating its exiled leaders as

equal partners in war and at the peace tables. For a decade, the US

voted to let the Khmer Rouge keep the Cambodia seat at

the United Nations, and, through a political coalition, supported the

regime’s army fighting against Vietnam. When pushed, US officials would

say that yes, they were aware of “the violence Pol Pot perpetrated,” but

Cambodian independence was more important.

Hollywood, though, helped change that narrative by producing a film

that shattered public ignorance and brought to life the stories that

many journalists were writing. I worked as a consultant on The Killing Fields, which told the true story of New York Times

reporter Sydney Schanberg and his Cambodian colleague, Dith Pran. They

cover the war together, with Schanberg escaping at the end and Pran

forced to stay behind and suffer through the Khmer Rouge regime. It was

devastating. Finally, the general public understood that Pol Pot had

overseen another Holocaust. The film won three Academy Awards and

forever changed the debate.

I kept thinking I’d turn a corner and I’d see

real life. I’d run into some kids playing a game, or some women

talking….Cambodians are lively people, but there was nothing. What was

missing was almost profoundly more upsetting to me than what was there.”

A year later, my own investigative history of the Khmer Rouge, When the War Was Over,

was published. It offered one of the first full descriptions of how the

regime came to power, portraits of its leaders and the victims, and how

the murderous and incompetent revolution ruined the country and its

people, erasing one of Asia’s oldest societies. I relied on Khmer Rouge

records and interviews with survivors and regime leaders, and included a

full description of our fateful 1978 trip, even documents showing how

the Khmer Rouge manipulated our every move. Importantly, the book argued

that the regime had committed genocide.

This time around, the response was warmer. Reviews in The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and

others praised it, calling it a “work of the first importance” and “the

definitive book on the Cambodian revolution.” But that didn’t bring a

trial any closer. Cambodians had to wait another 20 years—until

2005—before the international community officially recognized the hell

they’d endured by creating a war crimes tribunal under the auspices of the United Nations and Cambodia.

Given all of that history, I was surprised when the Khmer Rouge defense attorneys resurrected the now-forgotten debate about the difference between my reporting and Dudman’s.

I was the first to testify; Dudman was to follow me weeks later as a

defense witness. Red-robed judges presided from an elevated bench. Below

them, purple-robed prosecutors and victims’ attorneys sat on one side,

black-robed defense attorneys on the other. A bulletproof glass wall

separated the courtroom from an auditorium, where the

general public—including Cambodians and foreign visitors—listened

through headphones to testimony translated into French, English, or

Cambodian. I sat in the witness chair, facing the judges, my back to the

audience.

It is not enough to report what you saw….You

must consider what you were not seeing, what the country was like

before, and keep asking questions. Genocide is a story few people want

to hear, and that those in power often don’t want told.

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne began by asking me to

explain how I had reached my conclusions in 1978. “I kept thinking I’d

turn a corner and I’d see real life. I’d run into some kids playing a

game, or some women talking,” I said. “Cambodians are lively people, but

there was nothing. What was missing was almost profoundly more

upsetting to me than what was there.”

The prosecutors came next, asking mostly friendly questions. But I

was treated as a hostile witness by the defense attorneys representing

the two surviving senior Khmer Rouge leaders on trial for crimes against

humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, and genocide. They

pitted me against Dudman, pointing out that I had been just 31 at the

time of the trip, while he had been a 60-year-old diplomatic

correspondent with a distinguished career. The defense attorney asked

why the court should accept my analysis that the regime was guilty of

genocide when Dudman had won the prestigious accolades for his more

generous interpretation.

I expressed respect for Dudman’s integrity. But it isn’t easy to

politely disagree after being sworn to tell the truth in a case

involving the death of two million Cambodians. As far as I was

concerned, the matter had long since been settled. Documents and

eyewitness accounts discovered and amassed for the trial show the Khmer

Rouge were among the 20th century’s worst criminals. Tuol Sleng, the

regime’s main prison and torture chamber where thousands were falsely

accused and executed, had even been turned into a gruesome museum that

has become the most popular tourist spot in Phnom Penh.

The defense then called Dudman. Now 97, he testified by remote video

link from Bangor, Maine. He was alert for his age, and honest. While at

times he gave exact and riveting details of our trip, he often admitted

that his memory failed him.

Dudman stood by his reporting, saying he wrote what he’d seen and

experienced. He said that when he wrote the articles, he believed he was

telling the truth.

The defense attorney then told Dudman that I’d said I admired him,

but was saddened when he gave Pol Pot the benefit of the doubt. Dudman

answered that no one likes to be criticized. He said he had shown a

reporter’s skepticism. But he credited me with having spent more time in

Cambodia than he and said I had “a longer perspective.”

Then the defense asked Dudman if, in hindsight, he considered his

reporting “too positive or too uncritical.” To everyone’s apparent

surprise, Dudman said yes. He had changed his mind about the Khmer

Rouge.

“From everything that I have read since then, I think there was genocide under the Pol Pot regime,” he said.

The defense had lost Dudman.

I found his comments heartening and admirably self-deprecating. It is

not enough to report what you saw. Indeed, covering a tyrannical regime

that controls your every move and determines everything you hear and

everyone you come in contact with requires more than skepticism. You

must consider what you were not seeing, what the country was like

before, and keep asking questions. Genocide is a story few people want

to hear, and that those in power often don’t want told.

Recently, I telephoned Dudman and asked about his testimony. He said he stood by his answers in court and referred me to an article he wrote for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch not long after he testified.

In it, he wrote that our entire 1978 trip and what

came afterwards had left him “troubled.” “I wonder how I would have

behaved if I had been a correspondent in Germany during the early rise

to power of Adolf Hitler. Would I first have tried to report his side of

the story? How long would it have taken me to realize that he was all

bad and that any sympathy or even-handedness would have been misplaced?

The short answer is I don’t know.”

Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were found guilty of crimes against

humanity and sentenced to life in prison. Their trial on charges of

genocide continues.

Elizabeth Becker is the award-winning author of When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge. She has been the International Economics Correspondent for The New York Times, a foreign correspondent for The Washington Post, and Senior Foreign Editor of National Public Radio. Video of the tribunal is available here.

No comments:

Post a Comment