It pays to be friends with Beijing, but why is big China wooing small Cambodia?

Visit by Xi Jinping highlights his bid to use impoverished neighbour as an example of what Beijing can offer its potential allies

In

the early 1970s, Chinese leaders Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai accommodated the

exiled Cambodian prince Norodom Sihanouk and made him an honoured state guest

to demonstrate China’s support for small countries fighting imperialism.

China’s vision of

the world has changed much since, but its strategy of using Cambodia to

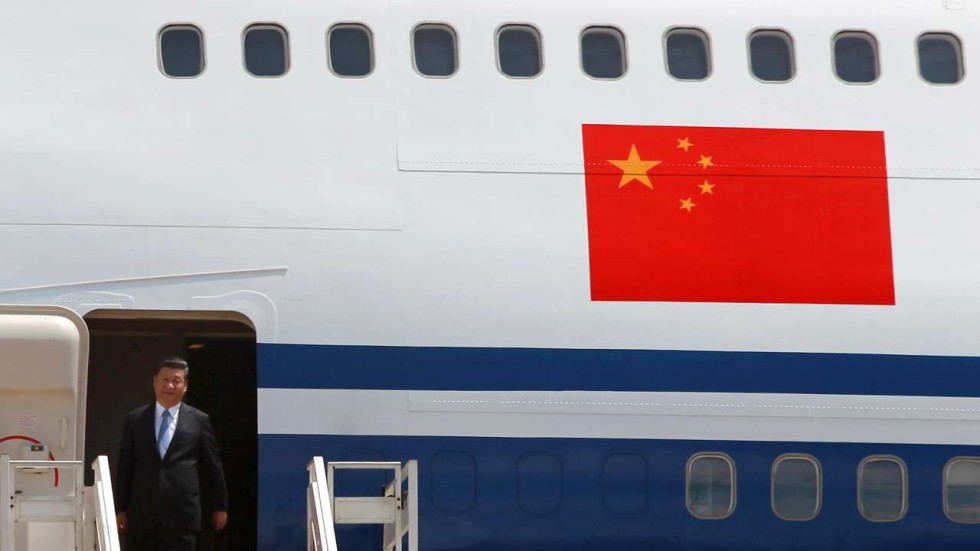

showcase Beijing’s big picture has not. When Chinese President Xi Jinping

landed in Phnom Penh, he had a clear message to deliver not only to

impoverished Cambodia but also other Asian countries: stay close to China to

gain from its growing richness and regional power.

China is putting

its hopes on the absolute support of Cambodia, its most loyal friend in the

10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations, to build closer relations

with the bloc. It hopes to counterbalance Washington’s influence in the region,

and to show potential allies what Beijing can offer in terms of trade growth,

infrastructure development and financial aid.

“China can use projects in Cambodia

as examples to get other countries on board,” said Victor Gao, a businessman

who had worked as a translator for Chinese leaders in the 1980s, at a forum in

Beijing earlier this week.

If Cambodia can gain from China’s One

Belt, One Road initiative, a brainchild of Xi to push Chinese investments

abroad along ancient trade routes, it can help the scheme gain support from

other poor countries that aspire to develop, according to Gao.

In 2015, China

invested more money into Cambodia, a country with 16 million people and a per

capita gross domestic product of US$1,200, than all other countries combined.

For every five dollars of capital spending in Cambodia, one dollar is from

China.

“Cambodia is China’s iron buddy,”

said Zhai Kun, a professor of international relations at Peking University.

“It’s China best friend, and China clearly appreciates it.”

The firm handshakes between Xi and

Norodom Sihamoni, the son of Sihanouk, were a sign of comradeship and mutual

trust. They marked a sharp contrast from the ties between the US and its

longstanding ally in Asia, the Philippines. Its president, Rodrigo Duterte, is

publicly calling US President Barack Obama a “son of a whore” and telling him

to “go to hell”.

As China’s flexing of its economic, political

and even military muscles in Asia is causing uneasiness and sometimes strong

responses from Washington and its allies, China is in need of friends. Cambodia

has more than once, including in 2012, stopped Asean from publicly condemning

China’s conduct in the South China Sea, even at the cost of causing irritation

in other Southeast Asian countries.

Meanwhile, as its population gets richer and

older, China is treating Southeast Asia as a place to seek high investment

returns.

“In the coming two decades, Asean will be one of

the fastest-growing economies in the world, just like what China did in the

1990s, and it’s a vast investment chance that China won’t miss,” said Chu Yin,

a professor with the University of International Relations.

To be sure, while Beijing has won the hearts of

the Cambodian royal family, Chinese investors need to do more to ensure that

the benefits of Chinese investments are shared by common people, and that these

inflows won’t cause environmental havoc.

However, Zha Daojiong, a professor with Peking University, said at

the forum last week that it was a long-term process to bring small countries

into China’s orbit. “Other countries do not have an obligation to appreciate

One Belt, One Road,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment