China Is Transforming Southeast Asia Faster Than Ever

Bloomberg | 5 December 2016

-

Rising Chinese labor costs send companies to Cambodia and Laos

-

Countries becoming more incorporated with China’s supply chain

China’s investment is transforming its smaller Southeast

Asian neighbors like never before while helping turn Cambodia, Laos and

Myanmar into bigger destinations for its exports.

That’s driving

some of the world’s fastest economic growth rates and providing Chinese

companies with low-cost alternatives as they seek to move capacity out

of the country. It’s also helping Asia’s largest economy and nations in

its orbit adapt to what looks more and more like a new era of waning U.S. commitment to the region from a more inward-looking administration of President-elect Donald Trump.

"China’s

definitely looking at these countries in general as an area where it

can sell products and get good return for its investments," said Edward

Lee, an economist with Standard Chartered Plc in Singapore. "China

itself is getting more expensive for its companies, and that’s

reinforcing this trend."

China is investing in everything from railroads to real

estate in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar -- the frontier-market economies of

the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Belt, Road

In landlocked Laos, work started

last year on the China-Laos railway, which will stretch 414 kilometers

(257 miles) from the border to the capital, Vientiane. The project, part

of Xi’s One Belt, One Road initiative, will cost $5.4 billion,

according to Xinhua. Xi met last week with Lao Prime Minister Thongloun

Sisoulith in Beijing, where he pledged stronger ties.

Myanmar,

which is liberalizing its economy and adopting market reforms after a

transition to democracy, is forecast by the International Monetary Fund

to expand 8.1 percent this year, the fastest in the world after Iraq.

De-facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi has been quick to engage China since

taking office this year, including visiting

Xi in Beijing. China is its largest trading partner, accounting for

about 40 percent of Myanmar’s total last year, and is building a special

economic zone, power plant and deep-water seaport on the west coast.

Cambodia’s economy is projected to grow 7 percent this

year, while Laos is set for 7.5 percent expansion. Faster growth has

also translated into rising income levels and lower poverty. Based on

the most recent data from the World Bank, the number of people living on

$1.90 a day in Cambodia dropped

to 2.2 percent of the population in 2012 from 30 percent in 1994. In

Laos, the poverty rate is 16.7 percent, down from 22.9 percent in 1992.

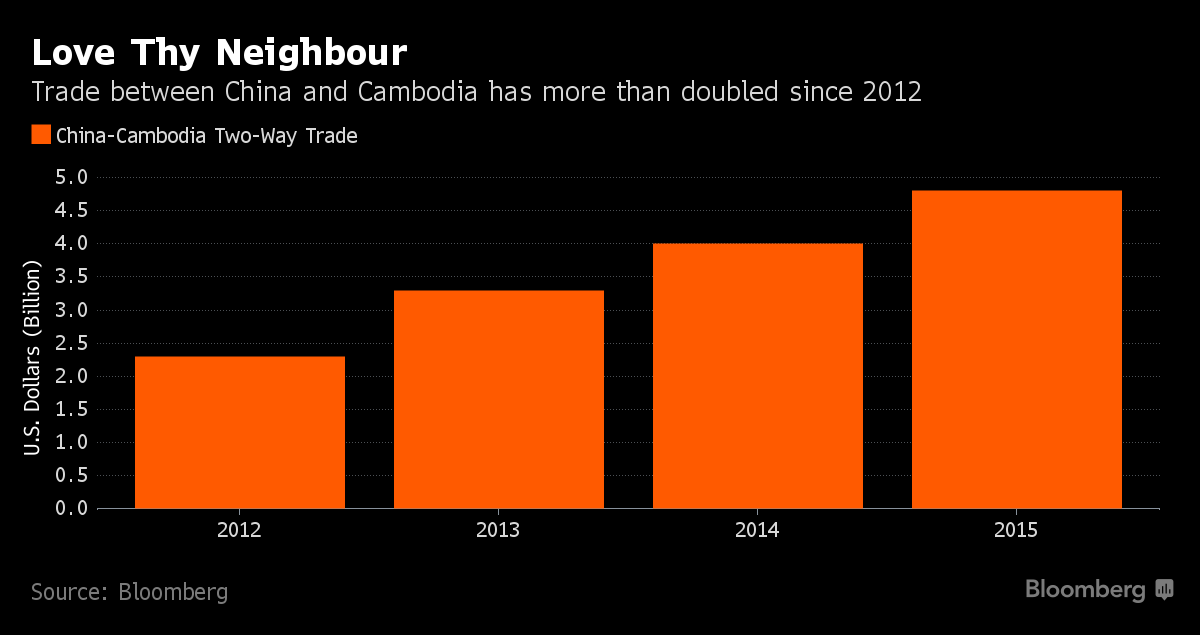

As Sino-Cambodian relations have flourished, so has trade,

with two-way commerce climbing to $4.8 billion last year. That’s more

than double from 2012, the year Cambodia warmed up to Beijing by opposing mention of China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea during a regional summit in Phnom Penh.

Most

Chinese money flowing in to Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar is lending on

highly concessionary terms to finance construction projects run by

Chinese firms, especially in Laos, said Derek Scissors, Washington-based

chief economist at China Beige Book International, who specializes in

studying the country’s foreign investment. Chinese construction and

investment since 2005 equal about 15 percent of Lao GDP, which it

couldn’t have financed from other nations, he said.

The share of

the Lao population with access to electricity rose from 15 percent in

the mid-1990s to almost 90 percent in 2014, though the power

grid increasingly faces new challenges from demand growing by an average

of 13 percent a year, according to a World Bank report.

"The

power sector is basically Chinese-built, bringing electricity to the

majority of the population," while China built several hydroelectric

plants to increase electrification, Scissors said. "There were grand

plans for Myanmar, but investment and construction actually realized is

more conventional, in the energy and mining sectors."

Garments, Shoes

Cambodia,

Laos and Myanmar are becoming more incorporated with China’s supply

chains, buying intermediate goods from its factories and selling

consumer items such as garments and shoes that are often made

by companies owned or funded by China. Its imports from the three

Southeast Asian economies more than doubled in the past five years, IMF

data show.

The Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone, where a number of Chinese companies have set up factories.

Photographer: Brent Lewin/Bloomberg

“This reliance on a narrow production and export base has many downsides,” the IMF said in a recent report. “A majority of Cambodian garment factories concentrate on cut-make-trim processes, which are at the bottom of value chain and also small part of the overall production. As a result, firms in Cambodia have limited leverage and autonomy.”

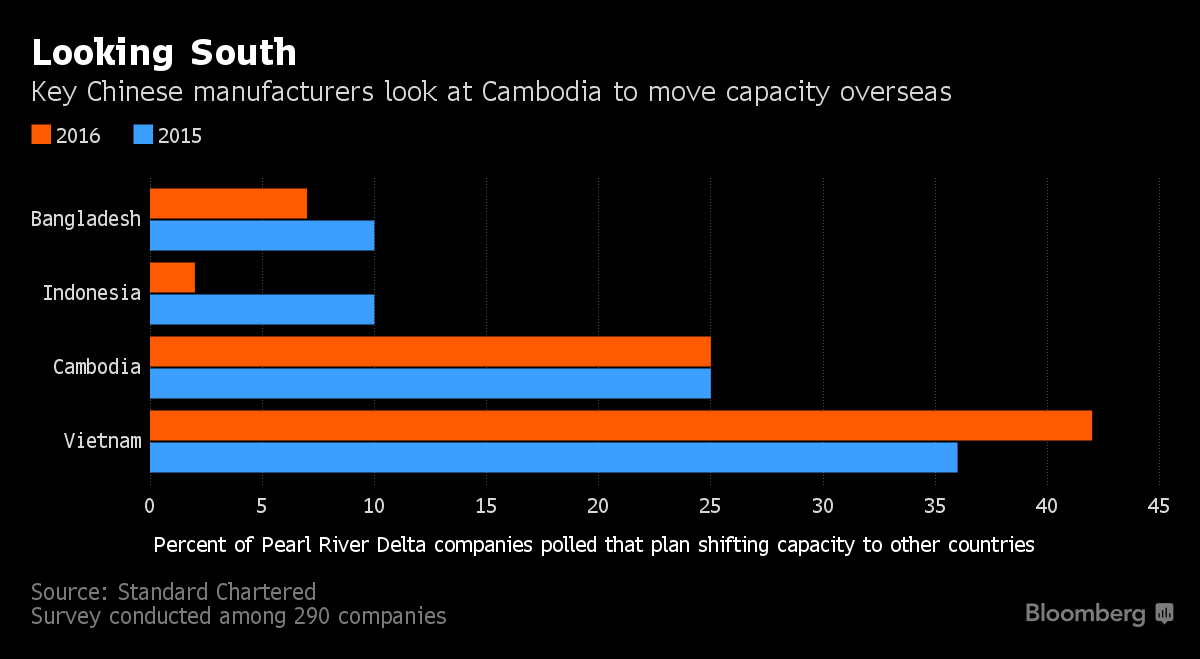

Cambodia has gained particular appeal for Chinese manufacturers seeking to relocate, which aligns with China’s strategy to export industrial capacity through initiatives such as One Belt, One Road. Cambodia’s $121 average monthly wage is just a fifth of China’s $613 average, according to the International Labour Organization in Geneva.

"These economies are getting a lot of money and opportunity from China," he said. "If wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few, that may lead to problems and instability. The key here is developing a middle income group that Chinese companies will be targeting as a consumer."

No comments:

Post a Comment