Could Sam Rainsy’s resignation help end Hun Sen’s reign in Cambodia?

The ruling

Cambodian People’s Party may have forced its nemesis to resign, but

attempts to sue the opposition out of existence will not solve its

biggest headache – post-war baby boomers

South China Morning Post | 19 February 2017

Cambodia’s colourful opposition

leader Sam Rainsy, in exile in France since 2015, stunned his loyal

supporters by resigning this week amid a sharp deterioration in the

country’s political climate with less than four months before

all-important commune elections that will act as a bellwether for next

year’s national polls.

The resignation was widely viewed as an attempt to

outmanoeuvre legal efforts by Prime Minister Hun Sen to ban politicians

with convictions from standing for public office – Rainsy has

convictions for defamation against Hun Sen and the ruling Cambodian

People’s Party (CPP) that are widely seen as politically motivated.

This leaves Kem Sokha at the opposition helm and potentially the country’s the next leader.

Cambodian

Prime Minister Hun Sen threatened to seize the property of opposition

leader Sam Rainsy and sell the party's headquarters if he wins a

defamation case against the exiled politician.Photo: AFP

Cambodian

Prime Minister Hun Sen threatened to seize the property of opposition

leader Sam Rainsy and sell the party's headquarters if he wins a

defamation case against the exiled politician.Photo: AFP

It’s a political fracas that will also be watched

closely by Beijing, which backed Hun Sen in the 2013 election and has

tipped billions of dollars into Cambodian infrastructure as part of its

wider strategy to open trade routes along its southern flank.

Ren Chanrith, coordinator of political dialogue at

the Youth Resource Development Programme, said the CPP was attempting

to minimise opposition influence and this was weakening democracy and

checks and balances. “The image of Cambodia in the international

community has been damaged because they can see that the ruling party is

only trying to fight for their own power and Cambodia is moving to

dictatorship,” he said.

By banning Taiwan’s flag, Cambodia adds to Taipei’s woes with Beijing

Lawsuits launched by members of the CPP and the

jailing of senior opposition figures have dominated the political

agenda, with the government struggling to win electoral support,

particularly among the youth.

Sam Rainsy has accused the National Assembly of

rubber stamping CPP legislation, and says the latest proposals by Hun

Sen are really aimed at dissolving his Cambodian National Rescue Party

(CNRP).

“This law aiming to institutionalise a one-party

system is being tailor-made for me – in my capacity as CNRP president –

since the CNRP is the only opposition party represented at the National

Assembly and the only party that can defeat the CPP,” he said.

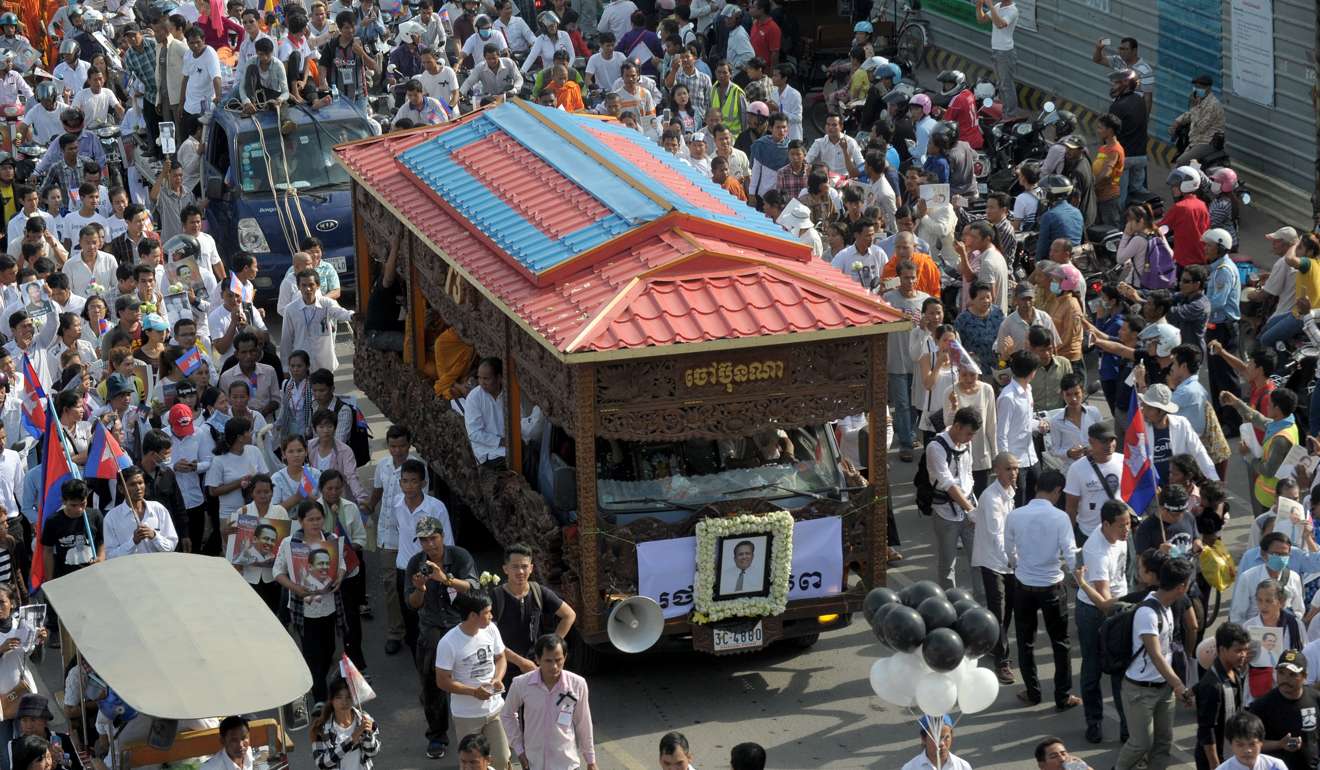

Thousands

of people take part in a funeral procession in Phnom Penh on for Kem

Ley, a Cambodian political analyst and pro-democracy campaigner who was

shot dead in broad daylight on July 10 at a convenience store. Photo:

AFP

Thousands

of people take part in a funeral procession in Phnom Penh on for Kem

Ley, a Cambodian political analyst and pro-democracy campaigner who was

shot dead in broad daylight on July 10 at a convenience store. Photo:

AFP

Immediately after the weekend resignation, Hun Sen

filed yet another defamation lawsuit, against political analyst Kim Sok

– accused of blaming the CPP for the murder of fellow analyst Kem Ley,

who was gunned down in broad daylight in July.

Speaking during the inauguration of the

Cambodian-Chinese Friendship Bridge, the prime minister also said he had

asked police to monitor Kim Sok and warned that anyone who disturbed

national security should “prepare their coffin”.

“Do not run away, as you have claimed yourself to

be a strong person,” he said, as China’s latest contribution to the

Cambodian economy was unveiled. “If you do not have money, your house

will be sold.”

Sam Rainsy fled into self-imposed exile in France

after receiving a jail sentence for defamation two years ago. A

five-year jail term was also imposed in December over a Facebook post

and Hun Sen is also seeking US$1 million from him in another lawsuit.

Rainsy ban to protect airport, official claims

|

| Heavily armed Royal Cambodian Armed Forces members stand guard at the Phnom Penh International Airport in November last year after rumours Sam Rainsy would be returning to the country. Heng Chivoan |

Sam Rainsy, centre, greets supporters during a demonstration in Phnom Penh in 2013. Photo: AFP

Sam Rainsy, centre, greets supporters during a demonstration in Phnom Penh in 2013. Photo: AFP

Hun Sen is threatening to seize CNRP headquarters if he wins.

Observers close to the CPP say internal surveys

show a 30 per cent swing against the government is expected at the June 4

commune elections, which does not bode well for Hun Sen who is facing a

general election a year later.

Communes are clusters of villages where local

officials are elected every five years, providing an important harbinger

for the national polls to follow.

How good luck for Vietnam’s gamblers could force Cambodian casinos to fold

The ruling party has led Cambodia since the Khmer

Rouge were ousted from power in 1979, with Hun Sen at the helm amid

fluctuating fortunes since 1985.

The CPP was returned at the 2013 elections, but

lost 29 seats in the 123-seat parliament after the nation’s youth

shifted towards the CNRP.

Kem Sokha now leads the political opposition in Cambodia.Photo: AP

Kem Sokha now leads the political opposition in Cambodia.Photo: AP

Kem Sokha needs to increase the CNRP’s tally by

just seven seats to 62 in order to govern. On his side are Cambodia’s

post-war baby boomers.

At least 65 per cent of the population are under

the age of 30 and remain unmoved by Hun Sen’s warnings of conflict if he

is not re-elected next year. They are now providing the ruling party

with their biggest headache.

Cambodia’s Hun Sen demands US$1 million from exiled leader or he’ll seize opposition party headquarters

Unlike their parents, Cambodia’s youth demand high

paying jobs, smartphones and new motorbikes at a time when the economy

is showing signs of faltering.

A building boom appears almost over. Cambodia’s

biggest donor, China, has its own financial problems and foreign aid and

investment are far from guaranteed.

“The ruling party has tried many ways to eliminate

the opposition party, like court cases and through intimidation,” Ren

Chanrith said. “[But] in the psychological context the opposition party

is winning.”

Allegations of widespread cheating followed the

2013 poll, resulting in CNRP-led protests and long-running, sometimes

violent, battles between the police and anti-government demonstrators.

Opposition politicians have been bashed on the steps of parliament.

New political parties, including the resurrection

of Prince Norodom Ranariddh, whose career was ruined by convictions for

corruption, have surfaced amid speculation they were backed by Hun Sen

in an attempt to split the opposition and provide potential coalition

partners if the CPP fails to win a clear mandate in 2018.

“Hun Sen is trying everything. They need to win

back a lot of votes and the CPP are using every trick in the book to get

their way,” another political analyst, who declined to be named, said.

Kem Sokha does not enjoy the same international

profile as Sam Rainsy, who has been prominent in Cambodian politics

since the early 1990s. But as CNRP leader, he has strength among rural

voters and that is a serious challenge for Hun Sen who counts the

countryside as the heartland of his constituency.

A widening wealth gap, land grabbing, corruption

and access to health and education are key issues confronting villagers

in the countryside and analysts say this will play out at the commune

elections in June.

Mourners hold a portrait of Cambodian government critic Kem Ley during a funeral ceremony in Phnom Penh. Photo: AP

Mourners hold a portrait of Cambodian government critic Kem Ley during a funeral ceremony in Phnom Penh. Photo: AP

It’s a political equation that worries Hun Sen and one that Kem Sokha should relish.

However, the killing of Kem Ley stunned

free-speech activists, civil society groups and opposition politicians

alike and his alleged killer, Ouet Ang, has been listed for trial on

March 1.

The fear that followed among opposition ranks has been complicated by the rash of lawsuits.

Several members of the CNRP, contacted by This Week in Asia,

declined to comment on Kem Sokha’s appointment and his electoral

prospects. One prominent opposition spokesman said: “If it’s about

Rainsy’s resignation, I don’t want to comment ... too sensitive.”

Getting the opposition message out is proving difficult. ■

No comments:

Post a Comment