|

People search for their names on a voting list during commune elections in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, June 4, 2017.

© 2017 Reuters |

Cambodia: Revoke Ban on Election Monitors

New Threats to Civil Society, Free and Fair Elections

| 9 July 2017

| 9 July 2017

(Bangkok) – The Cambodian government should rescind its recent order restricting independent election monitoring groups, Human Rights Watch said today. On July 4, 2017, a month after the country’s flawed commune elections, the Interior Ministry issued a letter to two election-monitoring organizations to cease their activities in alleged violation of the country’s nongovernmental organization law.

The government’s action sets the stage for the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) to broaden restrictions on election monitoring prior to the 2018 national elections.

“The Cambodian government appears intent on quashing any challenges to its political control – and obviously doesn’t want any witnesses,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director. “Cambodia’s donors should call for the government to rescind these orders and ensure independent monitoring of the 2018 elections.”

The July 4 notice sanctions the Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL) and the Neutral and Impartial Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (NICFEC) on the basis that their election-monitoring consortium, the Situation Room, “does not reflect the neutrality” mandated by the Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organizations (LANGO).

The notice suggests that LANGO will become a more prominent tool in the government’s campaign against critics, civil society groups, and other perceived threats to its rule, particularly as next year’s elections draw near.

The Situation Room – a consortium of 40 Cambodian civil society groups collaborating on neutral, impartial, and independent election observation – released a final assessment of the commune elections on June 24 that identified serious election flaws, including an environment of intimidation and a lack of campaign finance transparency. While noting improvements in areas such as voter registration, the report concluded that “elections in Cambodia cannot yet be considered fully free and fair.”

On June 28, Prime Minister Hun Sen called for an investigation into the Situation Room: “The Interior Ministry must immediately take measures against what they have been doing under the pretext of election monitoring.” He questioned the group’s legal registration status and accused them of bias in favor of the opposition party. “How will they be punished?” he asked in the speech, delivered on the CPP’s 66th anniversary.

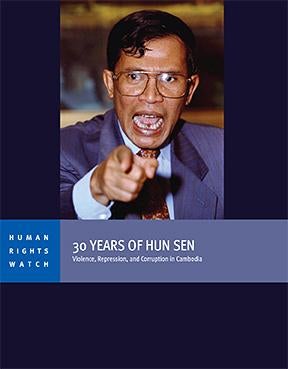

Hun Sen has held power for over 30 years since taking office in 1985. In a speech in February 2017, he responded to the idea of an opposition victory next year by threatening military force: “Some individuals … predicted that in 2018 they could win, and if we don’t hand over power to them, they will crush us. How can this happen if the troops are in my hand?”

Hun Sen’s threats and the ministry’s ban continue the CPP’s long history of intimidating civil society groups and alleging collusion with the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). In the lead up to the June 4 commune elections, Interior Ministry Spokesman Gen. Khieu Sopheak threatened human rights groups with government surveillance and investigation for allegedly supporting the opposition, which he later admittedwas an attempt to intimidate them from monitoring the election. More broadly, the government has in recent years increased its repression of human rights groups such as the Cambodian Human Rights and Development Association (ADHOC), a member of the Situation Room, by carrying out politically motivated prosecutions.

Banning the collaborative election monitoring of 40 civil society groups violates the rights to freedom of expression and association under international human rights law.

Cambodian elections have for decades been marked by violence and repression employed by the CPP to maintain power. The country’s electoral system is marred by systematic problems, including a politically biased election committee, lack of an impartial dispute resolution mechanism, partisan campaign regulations, and unequal access to media.

Human Rights Watch found that the recent commune elections were fundamentally flawed as a result of these structural biases, as well as the environment of intimidation fostered by the CPP. Such barriers to free and fair elections violate article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Cambodia is a party, which provides that every citizen, without discrimination on the basis of political opinion, shall have the right and opportunity to vote and be elected in genuine periodic elections.

The CPP has shown it will fight to preserve its rule in the 2018 elections by any means necessary, including amending legislation in order to increase its power over political parties and impede the opposition CNRP. On July 10, the National Assembly will vote on recently proposed amendments to the Political Parties Law that would force the CNRP to sever ties with its former leader, Sam Rainsy. Violations of the new provisions are punishable with a five-year ban or dissolution.

The Cambodian government appears intent on quashing any challenges to its political control – and obviously doesn’t want any witnesses.

Phil Robertson

Deputy Asia Director

The Situation Room is accused of violating article 24 of LANGO, which requires groups to operate under a vaguely defined obligation of “political neutrality,” for its reporting on the commune elections. The law was passed in August 2015 despite wide criticism from international and domestic groups over its severe restrictions on freedoms of association and expression.

LANGO, which Hun Sen threatened to use to “handcuff” unregistered groups, allows authorities to arbitrarily de-register or shut down organizations, and criminalizes activities by unregistered groups. Its restrictions on the right to freedom of association go well beyond the permissible limitations allowed by international human rights law. The law gives government ministries sweeping powers to shut down domestic and foreign organizations, unchecked by judicial review, and to prohibit the creation of new organizations. Since being passed, it has been used to threaten grassroots organizations working on land disputes and women’s rights.

After Hun Sen’s threat of investigation, the Situation Room released a statement declaring its role as a “neutral and impartial platform,” and stating its activities had concluded with its final report. Various coalition members have also asserted that the consortium was not a formal organization but rather a platform for collaboration and resource pooling, and thus had not violated LANGO’s registration requirements.

In addition to the letters to COMFREL and NICFEC, the Interior Ministry posted a general notification about the activity and financial reporting requirements for registered organizations under LANGO, which are burdensome and excessive. The announcement included a blanket warning to groups which it said had violated the law by failing to fulfill their reporting obligations, and issued a September 2017 deadline for compliance.

“Fears that the NGO law would be used to smother Cambodia’s thriving civil society are coming to pass,” Robertson said. “Hun Sen’s use of the law to prevent independent monitoring of the 2018 elections may just be an ugly prelude to its use more broadly against domestic and international organizations in the country.”

No comments:

Post a Comment