That’s All Right: The song that made a King

BBC | 5 July 2014

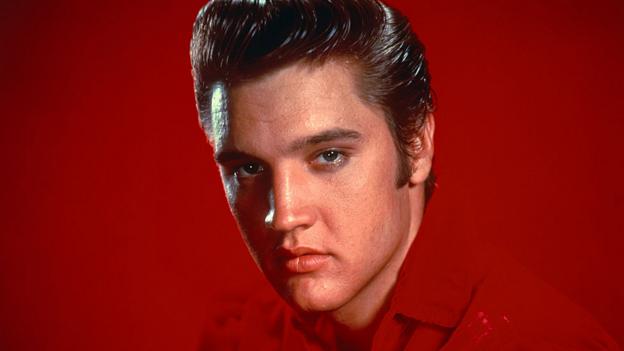

(Sunset Boulevard/Corbis)

When Elvis recorded his first single 60 years ago a star – and a myth –

were born. But why has his legend endured for so long? Dylan Jones

looks back.

On 5 July it is 60 years since Elvis Presley recorded his first

single, a rockabilly version of the 1946 blues song That's All Right at

Sam Philips' Sun Studios in Memphis, Tennessee. With this record, Elvis

captured lightning in a bottle. That’s All Right has become the lodestar

of rock ‘n’ roll, the song by which every other rock song should be

judged. It would be wrong to say that before this there was nothing –

there was jump blues, R&B, hillbilly, urban swing, Ike Turner and

even Bill Haley – but this song was the line in the sand, the vortex

through which the teenage demographic came of age.

One of the most defining moments of the 20th Century, it lasted just one minute and 57 seconds. When the recording session was done, bass player Bill Black said, “Damn. Get that on the radio and they’ll run us out of town.” “I cannot tell you [what style it was], even though I’ve been asked quite a few times,” said Scotty Moore, who played guitar on the track. “It wasn’t even really the lack of a drummer. I guess it was just a combination of several different styles rolled into one. Like we used to say then, and probably people still do today when you ask them how they do something, ‘I just did everything I could,’ you know?"

This

summer also sees the anniversary of Elvis's death, on 16 August, 1977.

Like the murders of JFK and RFK, or the deaths of Marilyn Monroe, John

Lennon or Kurt Cobain, Elvis Presley’s death is etched in the public

mind – whether we’re fans or not. Everyone over a certain age can

remember exactly where they were when they found out that Elvis was

dead. For more than twenty years, since the birth of rock’n’roll in

1956, Elvis had been part of the very fabric of American life. He was an

object of desire and worship the whole world over. A life suddenly

without Elvis was unthinkable, unimaginable.

We still feel his death today. A 2004 Samaritans survey of

Britain’s most emotional memories placed Elvis’s death at number 20,

after events such as the fall of the Berlin wall, Neil Armstrong walking

on the moon and the 9/11 attacks. Elvis also died during the peak of

punk rock, at a time when his own cultural relevance had hardly been

lower. Yet he was still considered to be the harbinger of rock ‘n’

roll’, the lightning flash that sparked a musical, social, cultural,

sexual and socio-economic revolution.

Cautionary tale

Punk

set out to destroy Elvis, or at least everything Elvis had come to

represent, yet Elvis destroyed himself before anyone else could.

However, nearly forty years after his death, the man just won’t go away.

He has penetrated the modern world in ways that are bizarre and

inexplicable: a pop icon while he was alive, he has become almost a

religious icon in death, a modern-day martyr crucified on the wheel of

drugs, junk TV and bad sex. And he has inspired several generations of

obsessives and impersonators, all of whom treat Elvis as some kind of

deity.

Elvis’s journey was the 20th Century’s most perfect example

of the Horatio Alger myth; although instead of achieving the American

Dream by leading an exemplary life, struggling valiantly against poverty

and adversity, Elvis gained wealth and success by catching sunshine.

And the story of Elvis possesses the sort of tragic narrative arc to

which we all seem hard-wired to respond. It is a cautionary tale, one

with no ambiguity: “What you are now, I once was; what I am now, you

will become.”

Whenever we catch the melodramatic strains of an old Elvis hit

playing on the radio, or in the back room of a downtown bar, who among

us begrudges those elemental – if overplayed – parts of popular culture a

respectful nod of acknowledgement, and perhaps even a secret inner

smile, irrespective of the fact that we have all heard these songs so

often their power to move us has long since been diffused? Who cares?

It’s Elvis, and no one begrudges Elvis, right?

A new religion

“The

death of Elvis Presley in 1977 provoked a gradual blurring of reality

and myth that prompted cultural critics to ponder whether he might

ultimately become the subject of religious frenzy,” wrote pop biographer

Peter Doggett, although anyone with even a passing interest in popular

culture would have anticipated this happening anyway. He may not have

been culturally relevant in 1977, but he was still Elvis. Doggett

continued: “By 1992, the BBC’s religious affairs correspondent could

write a book, Elvis People, with a blurb that claimed: ‘It poses a

serious question: are we witnessing the birth of a new religious

movement?’ Presleyism may one day have to fight for spiritual space

with Jacksonism, Lennonsim, and of course Cobainianity.”

However

the cult of Elvis had actually started on the day he died. Whether it

was sharp-featured Elvis you wanted, or the latter-day idol in all his

magisterial pomp, the King could supply it all. According to a 1993 CNN

and Time magazine poll, one American in five thought that Elvis was or

may be alive. It also revealed that while 79% of Americans believed that

Presley died in 1977, 16% said he was still among the living, and 5%

were not sure.

Not only is Elvis the most enduring American icon

of the post-war years, he is the pop god by which all others are

measured. Elvis was there before everyone, before The Beatles, before

The Rolling Stones, before the Sex Pistols or Nirvana – which is why it

felt so strange when he suddenly wasn’t there anymore.

And in the

beginning there was That's All Right, a record that is as revered now

as it was then. “It was like being hit with a truck filled with

happiness,” said the film director David Lynch about the first time he

heard the record. “It was a thrilling truck, and you know, I sort of

wish everybody could experience that feeling. You’ve heard these

stories. So many musicians when they heard Elvis for the first time,

they just slammed their head with their fist and just said, ‘Damn! This

is it!’ And it was just suddenly so obvious. It wasn’t there, and then

it was there."

No comments:

Post a Comment