One needs only to read the headlines and comment boards to see that this is the case. Nearly all issues of life, both spiritual and secular, are increasingly approached in an adversarial and binary manner. The middle ground, an already slender topography to begin with, has been further eroded by our preference for sound bites and hamfisted diatribes over actual conversation and critical thought. Now opinions can only be one of two things: right or wrong; a given person, either a friend or a foe. In such an environment, constructive dialogue and cooperation, those priceless qualities that we were supposed to have developed in elementary school, have become all but impossible.

Third Culture

Faith...from the hyphenated point of view

Christianity Today | 22 September 2014

Me Living That Hyphenated Life

One might ask what I am doing here, a young Korean-American pastor

blogging alongside such well-respected figures as Ed Stetzer and Amy

Julia Becker. I’m not sure, but I suspect it’s some kind of mistake. It

has something to do with an article I wrote last year for Christianity

Today, which was one of the twenty most read articles

for that year – number 12 to be exact, ahead of an interview with Billy

Graham, but behind an article about Tim Tebow, which is in itself a sad

commentary on the state of things. CT editor Mark Galli must have read

my piece and assumed that I could write like that all the time, and I

didn’t have the heart to tell the poor guy the truth.

Oh well, he’ll realize his mistake soon enough.

All joking aside, I am deeply honored and humbled by this opportunity,

and want to use this inaugural post to describe what you might find in

this blog. You will often find posts on fatherhood and my life as a

pastor, as well as discussions on race and diversity, and the incredibly

messy intersection between all of these issues.

But what is more central to this blog is not so much what I write about

as the perspective from which I do so. This blog is named “Third

Culture”, a term used by sociologists to describe individuals who don’t

fit neatly into one cultural category or another, be it ethnically,

racially, or culturally. For those kinds of people, they forge for

themselves a third culture, a kind of fluid identity which is a fusion

of diverse influences and perspectives.

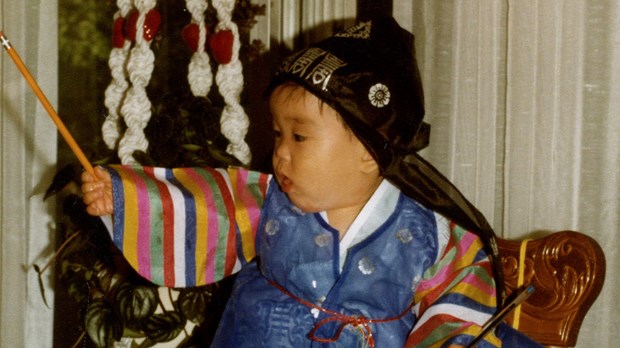

“Third culture” describes my own upbringing and point of view quite

well. I am a child of Korean immigrants, and yet cannot speak Korean

myself, and last visited that country when I was not yet potty trained.

As a result, I find it difficult to fully identify myself as a Korean

person. I am also an American who was born in Illinois, and yet still

feel a profound sense of otherness here in the US, the unfortunate

reality of many people of color who are perpetually considered

foreigners in the country of their birth. As a result, I am neither

fully Korean, nor American, but Korean-American, a discrete cultural identity.

My theological and even geographical backgrounds are equally eclectic. I

am an evangelical, but was born in the Roman Catholic church, and have

spent an equal number of years in a range of Christian traditions:

Presbyterian, Foursquare, Evangelical Covenant, Mennonite, and

currently, Free Methodist. Geographically, I was raised in a quiet

suburb of Chicago, but because my parents worked as small store owners,

also spent a good portion of my childhood in the inner city. As a

pastor, I have done ministry both in wealthy suburbs of Fairfax

Virginia, as well as the most economically depressed communities of DC,

the neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River.

As such, I find that the only way to identify myself appropriately is through a series of hyphenations: Korean-American. Evangelical-Ecumenical. Suburban-Urban. Dazed-Confused.

One might imagine that such an upbringing is a drawback, that a third

culture perspective fails to understand any one culture to its fullest

extent, or creates confusion and ambivalence about one’s identity. Both

are valid concerns. But I am now convinced that the third culture point

of view is of profound and increasing importance because it allows me,

and others like me, to better navigate a culture in conflict, which

describes our culture quite well.

One needs only to read the headlines and comment boards to see that

this is the case. Nearly all issues of life, both spiritual and secular,

are increasingly approached in an adversarial and binary manner. The

middle ground, an already slender topography to begin with, has been

further eroded by our preference for sound bites and hamfisted diatribes

over actual conversation and critical thought. Now opinions can only be

one of two things: right or wrong; a given person, either a friend or a foe.

In such an environment, constructive dialogue and cooperation, those

priceless qualities that we were supposed to have developed in

elementary school, have become all but impossible.

And this is why the third culture perspective is so important. While

certainly not immune to dogmatism, the life of an immigrant demands a

willingness to learn and adapt to diverse contexts and ideologies. That

has been our reality, figuring out how to honor our parents while still

looking cool to our middle school classmates, eating corndogs one day

and kimchi the next. We simply did not have the luxury to subscribe to

one cultural context to the exclusion of another - we were forced to straddle them.

As such, individuals who have grown up in a hyphenated context often

find it less difficult to hold two moderately diverse perspectives in

some sort of balance with one another. We know what it is to be American

but not American, to be Korean but not Korean, to be suburban and

urban, to be “both/and”, and not necessarily “either/or”. We have lived

our entire lives this way, at the intersection of cultures and

identities. We know that one does not necessarily have to choose one

over another, to be this or that - we are this and

that. The cultural terrain we have involuntarily traversed our entire

lives, although convoluted, has made us nimble, able to tread finer

lines that others now find it impossible to navigate.

Now it would be easy think of this as a perspective of compromise, as

if third culture people do not really believe anything, but that would

be a mistake. A third approach in no way precludes conviction, and

Christ sits solidly enthroned in my heart and in my life. No, third

culture is not so much a perspective of compromise as it is one of creation:

the creation of a third and new way, one that no longer sees all things

as a pitched and destructive battle between one ideology, culture,

person and the other. It is a way forward, a way of synthesis, which is

what we need now more than ever.

And so that is truly what I hope to accomplish through this blog: to

introduce a Christ-centered, loving, and thoughtful third-cultural

perspective, one that might help us imagine new ways to understand our

faith, but also, one another.

No comments:

Post a Comment