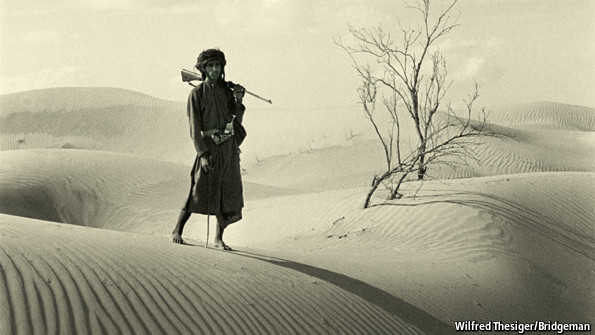

The Middle East

The tragedy of the Arabs

A civilisation that used to lead the world is in ruins—and only the locals can rebuild it

The Economist | 5 July 2014

A THOUSAND years ago, the great cities of Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo

took turns to race ahead of the Western world. Islam and innovation

were twins. The various Arab caliphates were dynamic superpowers—beacons

of learning, tolerance and trade. Yet today the Arabs are in a wretched

state. Even as Asia, Latin America and Africa advance, the Middle East

is held back by despotism and convulsed by war.

The blame game

One problem is that the Arab countries’ troubles run so wide. Indeed,

Syria and Iraq can nowadays barely be called countries at all. This

week a brutal band of jihadists declared their boundaries void,

heralding instead a new Islamic caliphate to embrace Iraq and Greater

Syria (including Israel-Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan and bits of Turkey)

and—in due course—the whole world. Its leaders seek to kill non-Muslims

not just in the Middle East but also in the streets of New York, London

and Paris. Egypt is back under military rule. Libya, following the

violent demise of Muammar Qaddafi, is at the mercy of unruly militias.

Yemen is beset by insurrection, infighting and al-Qaeda. Palestine is

still far from true statehood and peace: the murders of three young

Israelis and ensuing reprisals threaten to set off yet another cycle of

violence (see article).

Even countries such as Saudi Arabia and Algeria, whose regimes are

cushioned by wealth from oil and gas and propped up by an iron-fisted

apparatus of state security, are more fragile than they look. Only

Tunisia, which opened the Arabs’ bid for freedom three years ago, has

the makings of a real democracy.

Islam, or at least modern reinterpretations of it, is at the core of

some of the Arabs’ deep troubles. The faith’s claim, promoted by many of

its leading lights, to combine spiritual and earthly authority, with no

separation of mosque and state, has stunted the development of

independent political institutions. A militant minority of Muslims are

caught up in a search for legitimacy through ever more fanatical

interpretations of the Koran. Other Muslims, threatened by militia

violence and civil war, have sought refuge in their sect. In Iraq and

Syria plenty of Shias and Sunnis used to marry each other; too often

today they resort to maiming each other. And this violent perversion of

Islam has spread to places as distant as northern Nigeria and northern

England.

But religious extremism is a conduit for misery, not its fundamental cause (see article). While Islamic democracies elsewhere (such as Indonesia—see article)

are doing fine, in the Arab world the very fabric of the state is weak.

Few Arab countries have been nations for long. The dead hand of the

Turks’ declining Ottoman empire was followed after the first world war

by the humiliation of British and French rule. In much of the Arab world

the colonial powers continued to control or influence events until the

1960s. Arab countries have not yet succeeded in fostering the

institutional prerequisites of democracy—the give-and-take of

parliamentary discourse, protection for minorities, the emancipation of

women, a free press, independent courts and universities and trade

unions.

The absence of a liberal state has been matched by the absence of a

liberal economy. After independence, the prevailing orthodoxy was

central planning, often Soviet-inspired. Anti-market, anti-trade,

pro-subsidy and pro-regulation, Arab governments strangled their

economies. The state pulled the levers of economic power—especially

where oil was involved. Where the constraints of post-colonial socialism

were lifted, capitalism of the crony, rent-seeking kind took hold, as

it did in the later years of Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak. Privatisation was

for pals of the government. Virtually no markets were free, barely any

world-class companies developed, and clever Arabs who wanted to excel in

business or scholarship had to go to America or Europe to do so.

Economic stagnation bred dissatisfaction. Monarchs and

presidents-for-life defended themselves with secret police and goons.

The mosque became a source of public services and one of the few places

where people could gather and hear speeches. Islam was radicalised and

the angry men who loathed their rulers came to hate the Western states

that backed them. Meanwhile a vast number of the young grew restless

because of unemployment. Thanks to the electronic media, they were

increasingly aware that the prospects of their cohort outside the Middle

East were far more hopeful. The wonder is not that they took to the

streets in the Arab spring, but that they did not do so sooner.

A lot of ruin

These wrongs cannot easily or rapidly be put right. Outsiders, who

have often been drawn to the region as invaders and occupiers, cannot

simply stamp out the jihadist cause or impose prosperity and democracy.

That much, at least, should be clear after the disastrous invasion and

occupation of Iraq in 2003. Military support—the supply of drones and of

a small number of special forces—may help keep the jihadists in Iraq at

bay. That help may have to be on permanent call. Even if the new

caliphate is unlikely to become a recognisable state, it could for many

years produce jihadists able to export terrorism.

But only the Arabs can reverse their civilisational decline, and

right now there is little hope of that happening. The extremists offer

none. The mantra of the monarchs and the military men is “stability”. In

a time of chaos, its appeal is understandable, but repression and

stagnation are not the solution. They did not work before; indeed they

were at the root of the problem. Even if the Arab awakening is over for

the moment, the powerful forces that gave rise to it are still present.

The social media which stirred up a revolution in attitudes cannot be

uninvented. The men in their palaces and their Western backers need to

understand that stability requires reform.

Is that a vain hope? Today the outlook is bloody. But ultimately

fanatics devour themselves. Meanwhile, wherever possible, the moderate,

secular Sunnis who comprise the majority of Arab Muslims need to make

their voices heard. And when their moment comes, they need to cast their

minds back to the values that once made the Arab world great. Education

underpinned its primacy in medicine, mathematics, architecture and

astronomy. Trade paid for its fabulous metropolises and their spices and

silks. And, at its best, the Arab world was a cosmopolitan haven for

Jews, Christians and Muslims of many sects, where tolerance fostered

creativity and invention.

Pluralism, education, open markets: these were once Arab values and

they could be so again. Today, as Sunnis and Shias tear out each others’

throats in Iraq and Syria and a former general settles onto his new

throne in Egypt, they are tragically distant prospects. But for a people

for whom so much has gone so wrong, such values still make up a vision

of a better future.

No comments:

Post a Comment