HISTORY

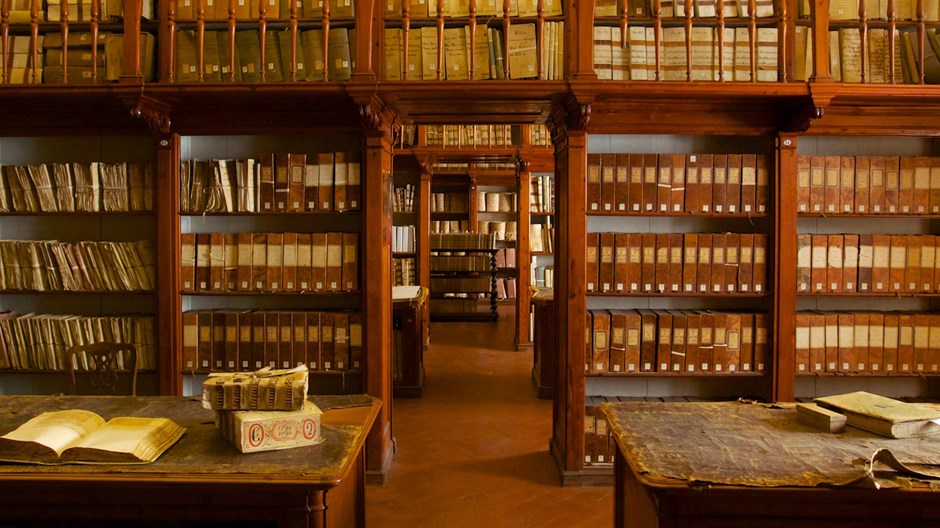

mathrong / Flickr

A Historian’s Reckoning with the Past

Grant Wacker reflects on how and why we look back.

American religious historians like me usually do not spend much time thinking about the rationale for doing what we do. We just do it. The upside is we usually get to the point pretty quickly, without a lot of methodological throat clearing along the way. The downside is we sometimes wander around the archives, not knowing exactly what we’re looking for, or what to do with our discovery once we’ve stumbled on it.

I think it’s useful to ponder how we reckon with the past and, more important, why.

The key word is reckoning. The other substantive word, past, is rich with nuances and complexities. But for present purposes I will define past simply as anything that happened more than five minutes ago. But what is reckoning? This word conventionally holds three meanings: counting, interpreting, and evaluating.

The first meaning—counting—is in a way the most fundamental, albeit the least interesting. It highlights the role of the raw data historians deal with. Laid out and stacked up, without interpretation or evaluation, they give rise to Jane Austen’s protest in 1818 about history: “I often think it odd that it should be so dull, for a great deal of it must be invention.” Which is to say that shuffling around raw data, like checkers on a checkerboard, makes for deadly reading. Nonetheless, the data have to be respected. Good books must “smell of the candle,” as the saying goes.

When I was in graduate school we called those data facts. That word has fallen out of fashion, which is unfortunate, for it aptly suggests that the data are out there, independent of us, and cannot be changed. The past really is past, forever gone.

But facts never come to us naked. They always come dressed in the clothes that historians dress them in.

That brings us to interpreting, the second meaning of reckoning. Interpreting is more interesting than counting. It highlights the role of perception. In an infinite sea of facts, historians must select the ones they perceive to be relevant to the question at hand. But selecting does not take place randomly. Historians choose the facts that feel meaningful, according to their personal experience, and who they are—white, black, male, female, Democrat, Republican, vegetarian, carnivore, husband, father, grandfather, the list goes on. So, for example, people like me who are entering retirement find themselves more interested in questions about mortality than in questions about, say, sexuality.

I think it’s useful to ponder how we reckon with the past and, more important, why.

The key word is reckoning. The other substantive word, past, is rich with nuances and complexities. But for present purposes I will define past simply as anything that happened more than five minutes ago. But what is reckoning? This word conventionally holds three meanings: counting, interpreting, and evaluating.

The first meaning—counting—is in a way the most fundamental, albeit the least interesting. It highlights the role of the raw data historians deal with. Laid out and stacked up, without interpretation or evaluation, they give rise to Jane Austen’s protest in 1818 about history: “I often think it odd that it should be so dull, for a great deal of it must be invention.” Which is to say that shuffling around raw data, like checkers on a checkerboard, makes for deadly reading. Nonetheless, the data have to be respected. Good books must “smell of the candle,” as the saying goes.

When I was in graduate school we called those data facts. That word has fallen out of fashion, which is unfortunate, for it aptly suggests that the data are out there, independent of us, and cannot be changed. The past really is past, forever gone.

But facts never come to us naked. They always come dressed in the clothes that historians dress them in.

That brings us to interpreting, the second meaning of reckoning. Interpreting is more interesting than counting. It highlights the role of perception. In an infinite sea of facts, historians must select the ones they perceive to be relevant to the question at hand. But selecting does not take place randomly. Historians choose the facts that feel meaningful, according to their personal experience, and who they are—white, black, male, female, Democrat, Republican, vegetarian, carnivore, husband, father, grandfather, the list goes on. So, for example, people like me who are entering retirement find themselves more interested in questions about mortality than in questions about, say, sexuality.

At this point in my life, I find a line from F. Scott Fitzgerald especially compelling. There is no difference between people, he judged, “so profound as the difference between the sick and the well.” That assessment of the human condition almost certainly involved his recurring bouts with alcohol. So too, historians see the past through the lens of their own lives. That lens obscures some vistas even it as it clarifies others. The trick is to know how to adjust for the former and make the most of the latter.

A good way to think about interpretation is to frame it as a conversation with the past. As in any conversation, one person speaks, and the other listens, considers, and responds. And then the first person listens, considers, and responds. So it is with interpretation. It is a conversation with the past that is never finished but always in motion. And perfectly tuned conversations really do happen, rarely with teenagers, but surprisingly often with small children. They stand as a testament to the reality of rational exchange with each other—and with the past.

These considerations bring us to the final meaning of reckoning: evaluating. This is by far the richest one. My advisor in graduate school, with pipe smoke billowing to the ceiling, liked to ask me about my seminar papers, “Well, Grant, what difference does it make? Why would anyone need to know that? Why would anyone want to know that?”

At first glance, the answer is simple. The “so what?” question helps us know what worked—and did not work—in the past to make life better, by both the past’s standards and the present’s. Or as the renowned Christian computer scientist Fred Brooks once said, “Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from bad judgment.”

Yet judging what did or did not work is not so easy. It requires honesty and diligence. Honesty means we admit up front, without hedging, that Christianity, like all cultural artifacts, has been embedded in time and place and change. Every shred of Christian doctrine and practice has been mediated to us through mundane experience.

Since Christian history has been embedded in time and place and change, it takes diligence to hear its distinctive notes. My colleague David Steinmetz captured the point perfectly. It is like learning a foreign language in a foreign land, through long immersion in the cultures of the past, patiently listening in the hope that listening will eventually lead to hearing, and hearing to understanding, and understanding to appreciation.

So the task is to hear the voices of the past—with our ears and minds and hearts. This means we let those voices speak again in all the pathos, power, and beauty of their original utterance. It means giving them a vote, maybe two votes.

Besides honesty and diligence, responsible evaluation of the past requires following certain rules. There are lots of rules, including ones about sifting the evidence, torturing it for reliability, and others. Two rules are especially important: charity and humility.

Charity calls us to assume the best of our historical subjects, unless the evidence compels us to judge otherwise, as sometimes it does—when, for example, people behead others to make a point. But in general, the golden rule of history is simple: Treat people of the past as we hope they would treat us. We need to remember, as the great Mormon historian Richard Bushman put it, that “someday we will meet in heaven the people we write about, and when we do, we will have to look them in the eye and account for ourselves. Have we told their story as fairly and as honestly as we know how? Have we told their story without distorting it in order to serve our own agendas?”

And humility. That goal is not “thinking less of yourself,” C. S. Lewis famously said, “but thinking of yourself less.” Humility requires us to acknowledge that Christians of the past grappled with life’s terrible moral dilemmas and wrestled with its terrible theological beasts, just as Christians today must do. Past Christians did not always solve those dilemmas or subdue those beasts. But they—Steinmetz again—often came up with answers we would not think to give and, more important, questions we would not think to ask. And sometimes just knowing that past Christians fought those fights, too, and somehow survived, Job-like, is payoff enough.

One of the great dangers of modernity is the assumption that truth resides mostly or even entirely in the present. History helps us see that we did not create ourselves. We stand on the shoulders of others. With his usual astuteness, my colleague Stanley Hauerwas has said that theology properly begins not by “gazing at our navels” but by recognizing that others have made us. “We owe them our gratitude.”

Consider how the British Marxist historian E. P. Thompson framed this insight in his classic book on the making of the English working class: “I am seeking to rescue the poor [stocking knitter], the Luddite [sheep shearer], the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver, the ‘utopian’ artisan, and even the deluded follower of [premillennialism], from the enormous condescension of posterity.” History too rightly begins with the humble recognition that others have made us—and they have gifts to give us.

Here is where things grow complicated yet exciting. All that I’ve discussed so far might be called the professional historian’s code of conduct. It authorizes admission into a secular history or religion department, or into the op-ed pages of publications like The New York Times. It forms a big part of what we call critical historical method. It is what students learn and professors teach in graduate school.

Yet Christian historians know there is more to the task. By Christian historians I do not mean Christians who teach in secular history or religion departments or write for secular venues like the The New York Times. Rather, I mean self-identified Christians who teach in self-identified Christian institutions like my own, Duke Divinity School. We might label such people church historians.

So what is special about the church historian’s task? The short answer is we need to add a fourth meaning to the concept of reckoning. Call it discerning.

Discerning involves more than just careful counting, interpreting, and evaluating. It involves identifying how the church has borne within itself a prophetic force or a prophetic vision somehow greater than the ceaselessly shifting social and cultural context in which it is embedded. To be sure, identifying exactly where God’s finger has drawn divine designs—where the “shook foil” of transcendence has manifested itself—is difficult at best, perilous at worst. As soon as we say that we have found it, it crumbles to the touch. We never get the design straight from the divine hand. It always comes mediated through fallible human hands. It forces us to admit that most of life is a “mixed and muddy affair.” Sometimes the best we can do, the Cambridge historian Herbert Butterfield wrote, is to “feel a little sorry for everyone.”

This problem, however, does not mean that we should just give up. Each historian will see God’s finger writing in history in different ways in different places. I see it in Pilgrim patriarch John Robinson, preaching to his flock in Holland in 1620 about the terrifying prospect of starting life over again in the New World. Listen to God’s voice, he urged: “I am verily persuaded that the Lord hath more truth yet to break forth out of His Holy Word.”

And in Anne Hutchinson’s lonely witness, insisting that God’s Holy Spirit might touch a woman as powerfully as any man. And in Abraham Lincoln’s call to both the North and the South to bind up the nation’s wounds. And in Emily Dickinson’s dogged pursuit of the God she could never quite find, or securely know.

And in the poetry of a Jewish woman, Emma Lazarus, who crafted the words forever inscribed on the base of the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” And in the courage of the men and women who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. over the Edmund Pettus Bridge to Selma in the face of snarling police dogs.

And in the prayer of Bob Pierce, the mercurial founder of World Vision: “Let my heart be broken with the things that break the heart of God.” And in the young American woman I recently saw on TV, working for Samaritans’ Purse in the Ebola crisis in West Africa. When a reporter asked her when she would be going home, she answered, simply, “I am home.”

All these ordinary people lived lives of extraordinary faith and courage.

And I see it in the mystery of the Eucharist, particularly in my own church, where people of both sexes and multiple races and ethnicities and ages and vocations and gifts and challenges stand together in radical equality at the Communion table. And in the inexplicable healing of my granddaughter’s heart when she was still unborn.

Sometimes I see God’s hand with special clarity in the insights of younger Christians. The first line of the first paper about the civil rights activist Fanny Lou Hammer, written by a first-year student at Duke’s Trinity College, read: “She told the truth with her life.”

And in an essay written by another first-year student at another college. She remembered her experience as a volunteer the previous year, just after graduating from a local high school. “Alissa was on my team,” the essay began.

She was born with a problem in her legs. Every day for the past six months, we had worked together at a community center in south Los Angeles. One day we were traveling together on the city bus. When it came to our stop, the driver tried to release the wheelchair platform but it would not operate. After some time it became clear that Alissa was stuck on the bus. The driver explained the situation to the passengers and asked them all to step off. People slowly unloaded, grumbling. Almost an hour passed before uniformed men from the Transportation Authority arrived with complicated metal devices that eventually brought Alissa down from the bus. To passers-by on the street it was a circus event.

Where was the real problem? In Alissa’s legs? Or in the inhumanity of the people on the street?

I see God’s hand in the closing words of a sermon preached by a young Methodist pastor fresh out of seminary, in her first charge, a small church in rural North Carolina: “We are all stranded on a desert island. Come rescue me.” Young though she was, she understood that it was the human condition itself that called for rescue.

The vision varies for every church historian. We see God’s hand in different ways in different places and in different times. But we do need to look for it. The reason is as simple as it is profound. Our lives will be enriched beyond measure if we look back as well as forward. We draw on the history of the church’s vast experience in order to identify God’s redemptive work in history.

To be sure, this commitment does not give church historians any free passes. Everything we say and write must stand the test of rigorous public accountability, just as any work by any professional historian must do. This commitment does, however, give us clues about where to start, how to rank the importance of events, and where the deep veins of meaning have resided. It might also give us clues about where the narrative truly ends.

Other thoughtful souls have joined us in this work. “I believe there are visions that come to us in memory, in retrospect,” said the novelist Marilynne Robinson in her novel Gilead. “That’s the pulpit speaking, but it’s telling the truth.”

The New York Times columnist David Brooks, who ranks as one of the most astute culture critics in America, echoed that insight. “Life has a way of blowing you off course,” he wrote. “People have a way of forgetting what they originally set out to do. Going back means recapturing the original aspirations.”

Church historians usually think more prosaically than novelists and journalists, but we too see things most clearly in memory, in retrospect.

My aim in teaching Christian history at Duke Divinity School for the past 23 years has not been to make new historians—except the doctoral students who sought that line of work. Rather, my aim has been to help my students hear, truly hear, the voices of the past echoing down the canyons of time, calling us to discern not only how the church has been embedded in its history, but also how God has worked through its history. That challenge prevents the church historian’s work from ever becoming just another job.

This article is adapted from Grant Wacker’s farewell address as he retired as Gilbert T. Rowe Professor of Christian History at Duke Divinity School. He is also author, most recently, of America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation (Harvard University Press, 2014).

No comments:

Post a Comment