Contents

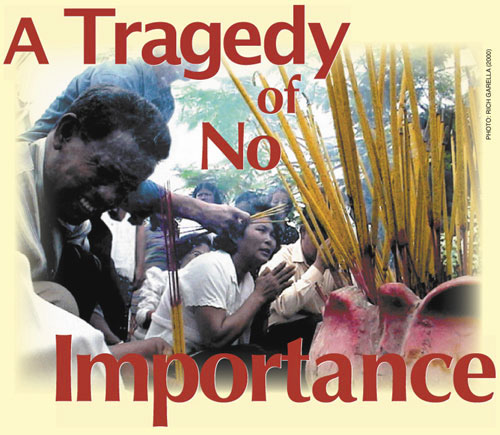

About A Tragedy of No Importance

This article was researched and written by Rich Garella and Eric

Pape. Both of us lived in Cambodia at the time of the grenade attack and

came to know many of the people affected by it. We saw what happened to

the ambitious effort to bring democracy and development to Cambodia,

and learned how the West chooses, finances and inoculates its winners,

and what happens when it abandons its losers.

PHOTO: RICH GARELLA

ON MARCH 30, 1997, about 200 of Rainsy’s supporters gathered to demand a cleanup of the corrupt justice system.

From the party’s offices they marched under the canopy of trees

shading quiet Street 240, past the Kantha Bopha children’s hospital and

the stable of the royal elephants. They emerged, under the baking

morning sun, in a rectangular park in the heart of Phnom Penh.

The park serves as a good map of the past decade of Cambodian politics. Immediately north,[n]

the golden walls of the Royal Palace sheltered Prince Ranariddh’s

father, the revered but politically diminished King Norodom Sihanouk. To

the northeast the Ministry of Justice stands as a mildewed memorial to

the dream of a global union française.

| |

PHOTO: RICH GARELLA

| |

| National Assembly in 2000 |

To the east, across Sothearos Boulevard from the site of the protest,

the central spire of the ornate National Assembly building rises above

overlapping gables in the Cambodian style. In the center of the park is a

towering statue of a Vietnamese soldier, a Cambodian soldier, and a

woman and child. And on the west side, beyond the boddhi trees,[n] is the Buddhist temple Wat Botum. A complex of mansions and guarded compounds, including one owned by Hun Sen,[n] sprawls out behind it.

A vendor was selling cubes of hand-cut sugarcane from a bright blue wooden pushcart.[s]

A passerby recognized a policeman with whom he had played soccer and

greeted him. “Something is going to happen,” the officer warned him.[s]

Across the park, in front of Wat Botum, a line of soldiers—Hun Sen’s

elite bodyguard unit—stood in formation, armed with AK-47 rifles and

B-40 rocket launchers. Perhaps because it was so early on a Sunday

morning, none of the young Western reporters were there yet.[n]

Abney had stopped off for breakfast. By the time he arrived,

Rainsy, standing on a chair, was wrapping up his speech. Abney started

across the street to greet him. He didn’t notice that the policemen had

pulled back, nearly out of sight. Abney heard a pop, like a bottle being

smashed, and he fell.

Those standing nearest took it in the legs. Metal cut through

flesh, muscle, bone. The center of the crowd flattened out. Han Mony,

Rainsy’s bodyguard, knocked his boss down and fell on top of him[s] just as a second grenade exploded

a few yards away. People were flayed alive as they dived for cover

behind fallen bodies. Fragments sliced through the windshield of a truck

carrying medicinal wine.

The third grenade exploded near the sugar cane cart where the

crowd was thickest, butchering garment factory workers, vendors, and

onlookers, splintering the cart and partially shattering a thick

concrete park bench. The fourth landed on a dirt pathway behind the

crowd, rolled to a stop, and detonated.[n] “It was out of a Kubrick movie,” Abney recalled. “People were flat on the ground, blown to shit.”[s]

Against the sudden silence, moans rose thinly in the air. Two

young women lay near the cart, one with her feet blown off. The other,

pale from blood loss, clutched at a motorcycle taxi driver’s shirttails,

begging for help. A 13-year-old boy, Ros Keam, lay clutching a protest

sign, his arms and legs pierced by shrapnel. Bodies lay scattered on the

pavement like broken puppets. Rainsy’s wife, Tioulong Saumura, heard a

woman screaming, “Your husband is dead! Your husband is dead!”[s]

As the smoke thinned, a few members of the National Assembly

slowly emerged and wept at the sight, accompanied by a surreal

combination of sounds: the slow, careful steps of late-arriving

photographers, the fading wails of the mortally wounded, and the pockets

of silence in between. An American journalist paced the sidewalk,

speaking into a cell phone, her voice cracking. “It’s horrible. It’s

horrible.”[s]

Within a few minutes, policemen began to arrive. Ignoring the

wounded protesters, they roped off the area and removed loudspeakers

left over from the rally. The woman with no feet sat up. “Hot…hot,” she

murmured, as her eyes began to glaze.

| |

PHOTO: DARREN WHITESIDE (ASIAWEEK)

|

The motorcycle taxi driver picked up one of the wounded girls, but a soldier told him to put her down, or die.[s] Helpless, he left her under a tamarind tree and stood by the palace wall, saying to himself, “She is dying, she is dying.”[s]

For thirty-five minutes no ambulances arrived.[s]

When they finally did, Phnom Penh’s three main hospitals became

obstacle courses of sprawling victims and slick pools of blood. The

truck driver’s head was delivered to the morgue in a cardboard box.

No comments:

Post a Comment