The Economist explains economics

What is the Nash equilibrium and why does it matter?

This week “The Economist explains” is given over to economics. For

each of six days until Saturday this blog will publish a short explainer

on a seminal idea.

The Economist | 6 Sept. 2016

ECONOMISTS can usually explain the past and sometimes predict the

future—but not without help. One of the most important tools at their

disposal is the Nash equilibrium, named after John Nash, who won a Nobel

prize in 1994 for its discovery. This simple concept helps economists

work out how competing companies set their prices, how governments

should design auctions to squeeze the most from bidders and how to

explain the sometimes self-defeating decisions that groups make. What is

the Nash equilibrium, and why does it matter?

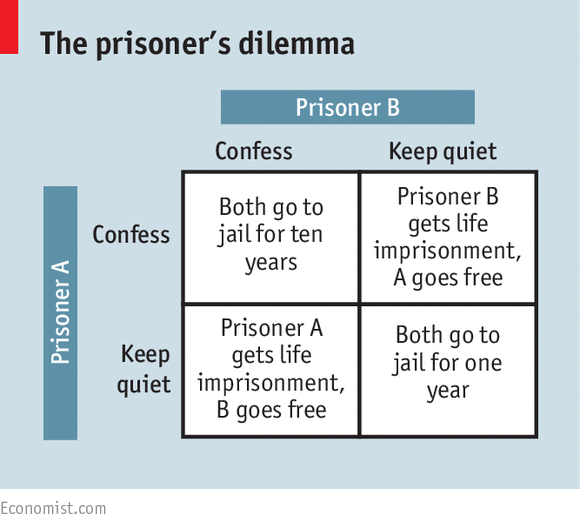

One of the best-known illustrations is the prisoner’s dilemma:

two criminals in separate prison cells face the same offer from the

public prosecutor. If they both confess to a bloody murder, they each

face ten years in jail. If one stays quiet while the other confesses,

then the snitch will get to go free, while the other will face a

lifetime in jail. And if both hold their tongue, then they each face a

minor charge, and only a year in the clink. Collectively, it would be

best for both to keep quiet. But given the set-up, an economist armed

with the concept of the Nash equilibrium would predict the opposite: the

only stable outcome is for both to confess.

In a Nash

equilibrium, every person in a group makes the best decision for

herself, based on what she thinks the others will do. And no-one can do

better by changing strategy: every member of the group is doing as well

as they possibly can. In the case of the prisoners' dilemma, keeping

quiet is never a good idea, whatever the other mobster chooses. Since

one suspect might have spilled the beans, snitching avoids a lifetime in

jail for the other. And if the other does keep quiet, then confessing

sets him free. Applied to the real world, economists use the Nash

equilibrium to predict how companies will respond to their competitors’

prices. Two large companies setting pricing strategies to compete

against each other will probably squeeze customers harder than they

could if they each faced thousands of competitors.

The Nash

equilibrium helps economists understand how decisions that are good for

the individual can be terrible for the group.

This tragedy of the

commons explains why we overfish the seas, and why we emit too much

carbon into the atmosphere. Everyone would be better off if only we

could agree to show some restraint. But given what everyone else is

doing, fishing or gas-guzzling makes individual sense. As well as

explaining doom and gloom, it also helps policymakers come up with

solutions to tricky problems. Armed with the Nash equilibrium, economics

geeks claim to have raised billions for the public purse. In 2000 the

British government used their help to design a special auction that sold

off its 3G mobile-telecoms operating licences for a cool £22.5 billion

($35.4 billion). Their trick was to treat the auction as a game, and

tweak the rules so that the best strategy for bidders was to make

bullish bids (the winning bidders were less than pleased with the

outcome). Today the Nash equilibrium underpins modern microeconomics

(though with some refinements). Given that it promises economists the

power to pick winners and losers, it is easy to see why.

Previously in this seriesMonday: Akerlof's market for lemons

Tuesday: The Stolper-Samuelson theorem

Tuesday: The Stolper-Samuelson theorem

Coming up

Thursday: The Keynesian multiplier

Friday: Minsky's financial cycle

Saturday: The Mundell-Fleming trilemma

Thursday: The Keynesian multiplier

Friday: Minsky's financial cycle

Saturday: The Mundell-Fleming trilemma

Over the past several weeks The Economist has run two-page briefs on six seminal economics ideas. Read the full brief on the Nash equilibrium, or click here to download a PDF containing all six of the articles.

No comments:

Post a Comment