|

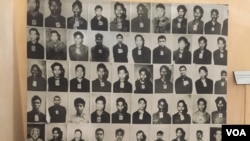

| A photograph at Toul Sleng Genocide Museum shows senior Khmer Rouge leaders, September 20, 2016. From left: Pol Pot (General Secretary of the Party and Prime Minister), Noun Chea ("Brother Number Two" and Deputy Party Secretary), Ieng Sary (Foreign Minster), Son Sen (Minister of Defence) and Vorn Vet (Deputy Prime Minister and responsible for the economy. (Nem Sopheakpanha/VOA Khmer) |

Digesting the Details Long After a Dinner with Pol Pot

VOA | 4 October 2016

History would prove the Swedes wrong, though Bergström himself disavowed the Khmer Rouge in 1979, a year after his return from Cambodia.

PHNOM PENH —

“Big power politics stopped them from doing anything.”

One dissenting voice, US Senator George McGovern, floated early on the idea of the United Nations intervening in Cambodia, but the motion would certainly have been vetoed by China in it position as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and the main supporter of the Khmer Rouge government in Phnom Penh, Bergström said.

“There was a discussion by Senator George McGovern to get the United Nations to invade Cambodia and save the people - a humanitarian invasion. But, of course, that would have been vetoed by China in five seconds,” he said.

Senator McGovern was a lone voice for intervention in Cambodia at a time when some prominent Western intellectuals were supporters of the Khmer Rouge regime, said Sophal Ear, associate professor at the Occidental College in Los Angeles.

“Senator George McGovern, who vehemently opposed the Vietnam War, was the lone voice for intervention in Cambodia because he knew something terrible was happening; yet, the senator got laughed at,” Sophal Ear told VOA Khmer.

Bergström and his colleagues were not the only Westerner sympathizers of the Pol Pot regime.

Scholars such as Noam Chomsky, Gareth Porter and George Hildebrand claimed there was nothing terribly wrong in Cambodia during the regime, Ear said.

The international community was also slow to acknowledge that genocide and other mass crimes were underway in Cambodia because the events had come so soon after the conclusion of the devastating war in neighboring Vietnam.

Tired of the decades of fighting in the region, the international community had already spilled and spent “blood and treasure in Southeast Asia and wanted nothing to do with Cambodia,” Ear said.

Bergström also said in his lecture that the international community knew what was taking place during the Khmer Rouge regime, but none wanted to make sacrifices to rescue the Cambodian people.

“They knew,” he said. “But I don’t think it would have changed that much because they would not sacrifice their power politics to save the Cambodian people. I don’t think so.”

When Vietnam invaded Cambodia in December 1978, the Khmer Rouge regime suddenly found itself an unlikely ally in the US, which was focused on containing Soviet Union expansion in Southeast Asia.

With strategic interests in mind, the US adjusted its policies and turned to provide financial support to the Khmer Rouge and other forces now based on the Thai border following the Vietnamese intervention in Cambodia. Khmer Rouge forces even received training from British special forces, Bergström said.

“When Vietnam invaded Cambodia and Pol Pot fled to the Western side, suddenly the United States changed policies and gave money to Pol Pot. Everything is possible when it comes to money and power. Suddenly our enemy, Pol Pot, becomes our friend. The secret service of the United Kingdom trained Pol Pot soldiers because they were fighting Soviet agents. It’s big power politics,” he said.

Following the Vietnamese invasion, Bergström and the other members of the Swedish delegation that visited Cambodia campaigned in Europe for the ousting of Hanoi’s troops and returning Pol Pot to power.

Swedish support for the Pol Pot regime may have helped to muddy international understanding of what had occurred in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, according to the Dinner with Pol Pot exhibition.

Perhaps the Swedish effort even contributed to the Khmer Rouge being seen in some quarters internationally as the legitimate rulers of Cambodia, and the rightful representatives of Cambodia at the UN General Assembly - a position the Khmer Rouge in exile on the Thai border held for many years after being ousted from power in Phnom Penh.

The international community knew what was happening inside Cambodia under the Pol Pot regime, but there was no mechanism in place by which to respond, said Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, which is dedicated to researching the Khmer Rouge regime.

National sovereignty is an important factor in understanding why it took the international community so long to acknowledge what was occurring inside Cambodia, said Yin Reaksmey, a Cambodian student at the University of London.

“I think it’s the matter of sovereignty because at that time Pol Pot was the one who ruled the nation. And, like it or not, the Western world had to respect a nation’s sovereignty,” he said.

Decades after Pol Pot’s mass killing in Cambodia, the international community helped to establish a court to seek justice for the victims of the regime, and in that way had, belatedly, demonstrated its’ concern for the millions who died during the regime, said Lat Ky, who monitors the Khmer Rouge war crime tribunal for local rights group Adhoc.

“The international community understands the suffering of the nearly two million Cambodians,” who died, Lat Ky told VOA.

In 1978 Gunnar Bergström travelled to one of the most terror filled countries of the 20th century.

A founding member of the Swedish-Cambodian Friendship Association, Bergström and three colleagues were invited to visit Cambodia that year by the Khmer Rouge regime.

As Marxist sympathizers, the group was trusted by the regime and offered the rare chance to witness Pol Pot’s vision of a perfect society – and, in return, were expected to describe Cambodia in those glowing terms on return to Sweden.

As Marxist sympathizers, the group was trusted by the regime and offered the rare chance to witness Pol Pot’s vision of a perfect society – and, in return, were expected to describe Cambodia in those glowing terms on return to Sweden.

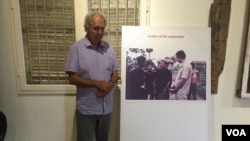

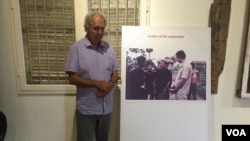

Gunnar Bergstrom pictured with a photograph of his meeting with Khmer Rouge cadres during his visit to Cambodia in 1978 at SRI Arts Gallery of the Documentation Center of Cambodia in Phnom Penh, September 12, 2016. (Nem Sopheakpanha/VOA Khmer)

After a two-week tour filled with official propaganda, stage-managed encounters with ‘ordinary people’ and denials by senior officials that anything was amiss in Democratic Kampuchea, the group returned to Europe to contradict accounts by Cambodian refugees of mass killing, torture and wide spread starvation.

History would prove the Swedes wrong, though Bergström himself disavowed the Khmer Rouge in 1979, a year after his return from Cambodia.

Returning to Cambodia in 2008, 30 years after his invitation to visit from Pol Pot, Bergström faced up to the human implications of what his visit had meant, and his endorsement of a regime that was responsible for the deaths of up to a quarter of the Cambodian population – an estimated 1.7 million people. His visit in 2008 led to an exhibition: Dinner with Pol Pot, which reflected on the Swedish delegation’s 1978 visit.

On September 12, Bergström was again in Phnom Penh. This time he was delivering a lecture about the Khmer Rouge, super power politics, and what had gone so terribly wrong for Cambodia.

An important point in Bergström’s recent lecture was the role of geopolitics in the Cambodian tragedy, primarily the strategic interests of the US, China and the then-Soviet Union and how that influenced what took place in Cambodia.

History would prove the Swedes wrong, though Bergström himself disavowed the Khmer Rouge in 1979, a year after his return from Cambodia.

Returning to Cambodia in 2008, 30 years after his invitation to visit from Pol Pot, Bergström faced up to the human implications of what his visit had meant, and his endorsement of a regime that was responsible for the deaths of up to a quarter of the Cambodian population – an estimated 1.7 million people. His visit in 2008 led to an exhibition: Dinner with Pol Pot, which reflected on the Swedish delegation’s 1978 visit.

On September 12, Bergström was again in Phnom Penh. This time he was delivering a lecture about the Khmer Rouge, super power politics, and what had gone so terribly wrong for Cambodia.

An important point in Bergström’s recent lecture was the role of geopolitics in the Cambodian tragedy, primarily the strategic interests of the US, China and the then-Soviet Union and how that influenced what took place in Cambodia.

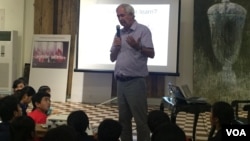

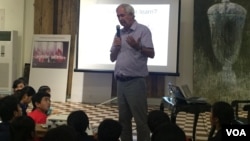

Gunnar Bergstrom delivers a public lecture to a group of students and general audience at SRI Arts Gallery of The Document Center of Cambodia, September 12, 2016. (Nem Sopheakpanha/VOA Khmer)

Strategic interests of super powers fanned the flames of conflict in Cambodia, and the international community was unable to put out the fire once it had begun to rage.

“Cambodia became the center of the conflict between China and the Soviet Union, and partly the US…. The interests of the Cambodian people had disappeared in thin air,” Bergström said in his lecture at the National Institute of Education.

The international community realized by 1978-79 that terrible events were taking place inside Khmer Rouge-controlled Cambodia, but it was either unable or unwilling to act, he said.“Cambodia became the center of the conflict between China and the Soviet Union, and partly the US…. The interests of the Cambodian people had disappeared in thin air,” Bergström said in his lecture at the National Institute of Education.

“Big power politics stopped them from doing anything.”

One dissenting voice, US Senator George McGovern, floated early on the idea of the United Nations intervening in Cambodia, but the motion would certainly have been vetoed by China in it position as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and the main supporter of the Khmer Rouge government in Phnom Penh, Bergström said.

“There was a discussion by Senator George McGovern to get the United Nations to invade Cambodia and save the people - a humanitarian invasion. But, of course, that would have been vetoed by China in five seconds,” he said.

File Photo: Former US lawmaker and presidential candidate George McGovern.

Senator McGovern was a lone voice for intervention in Cambodia at a time when some prominent Western intellectuals were supporters of the Khmer Rouge regime, said Sophal Ear, associate professor at the Occidental College in Los Angeles.

“Senator George McGovern, who vehemently opposed the Vietnam War, was the lone voice for intervention in Cambodia because he knew something terrible was happening; yet, the senator got laughed at,” Sophal Ear told VOA Khmer.

Bergström and his colleagues were not the only Westerner sympathizers of the Pol Pot regime.

Scholars such as Noam Chomsky, Gareth Porter and George Hildebrand claimed there was nothing terribly wrong in Cambodia during the regime, Ear said.

The international community was also slow to acknowledge that genocide and other mass crimes were underway in Cambodia because the events had come so soon after the conclusion of the devastating war in neighboring Vietnam.

Tired of the decades of fighting in the region, the international community had already spilled and spent “blood and treasure in Southeast Asia and wanted nothing to do with Cambodia,” Ear said.

Bergström also said in his lecture that the international community knew what was taking place during the Khmer Rouge regime, but none wanted to make sacrifices to rescue the Cambodian people.

“They knew,” he said. “But I don’t think it would have changed that much because they would not sacrifice their power politics to save the Cambodian people. I don’t think so.”

When Vietnam invaded Cambodia in December 1978, the Khmer Rouge regime suddenly found itself an unlikely ally in the US, which was focused on containing Soviet Union expansion in Southeast Asia.

With strategic interests in mind, the US adjusted its policies and turned to provide financial support to the Khmer Rouge and other forces now based on the Thai border following the Vietnamese intervention in Cambodia. Khmer Rouge forces even received training from British special forces, Bergström said.

“When Vietnam invaded Cambodia and Pol Pot fled to the Western side, suddenly the United States changed policies and gave money to Pol Pot. Everything is possible when it comes to money and power. Suddenly our enemy, Pol Pot, becomes our friend. The secret service of the United Kingdom trained Pol Pot soldiers because they were fighting Soviet agents. It’s big power politics,” he said.

Following the Vietnamese invasion, Bergström and the other members of the Swedish delegation that visited Cambodia campaigned in Europe for the ousting of Hanoi’s troops and returning Pol Pot to power.

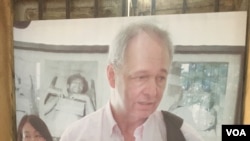

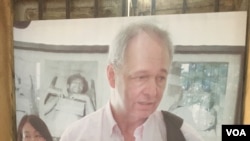

A photograph of Gunnar Bergstrom in an exhibition room at Toul Sleng Genocide Museum, September 20, 2016. (Nem Sopheakpanha/VOA Khmer)

Swedish support for the Pol Pot regime may have helped to muddy international understanding of what had occurred in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, according to the Dinner with Pol Pot exhibition.

Perhaps the Swedish effort even contributed to the Khmer Rouge being seen in some quarters internationally as the legitimate rulers of Cambodia, and the rightful representatives of Cambodia at the UN General Assembly - a position the Khmer Rouge in exile on the Thai border held for many years after being ousted from power in Phnom Penh.

The international community knew what was happening inside Cambodia under the Pol Pot regime, but there was no mechanism in place by which to respond, said Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, which is dedicated to researching the Khmer Rouge regime.

National sovereignty is an important factor in understanding why it took the international community so long to acknowledge what was occurring inside Cambodia, said Yin Reaksmey, a Cambodian student at the University of London.

“I think it’s the matter of sovereignty because at that time Pol Pot was the one who ruled the nation. And, like it or not, the Western world had to respect a nation’s sovereignty,” he said.

Decades after Pol Pot’s mass killing in Cambodia, the international community helped to establish a court to seek justice for the victims of the regime, and in that way had, belatedly, demonstrated its’ concern for the millions who died during the regime, said Lat Ky, who monitors the Khmer Rouge war crime tribunal for local rights group Adhoc.

“The international community understands the suffering of the nearly two million Cambodians,” who died, Lat Ky told VOA.

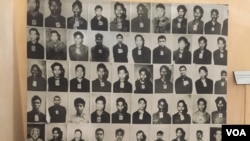

A photograph depicted Khmer Rouge victims at Toul Sleng Genocide Museum, September 22, 2016. (Nem Sopheakpanha/VOA Khmer)

The international community provides technical and financial support for the court in Phnom Penh to ensure the former leaders of the regime do not escape justice, Lat Ky said.

Bergström is one of the few former Western supporters of the Khmer Rouge who have publicly admitted to making a terrible mistake, and expressing regret.

He has offered this explanation as to what had clouded his judgment all those years ago in 1978, when he was a guest of Pol Pot:

“In retrospect, I think the whole trip was a propaganda trip and that we should never have undertaken the journey,” he said, according to the Dinner with Pol Pot exhibition.

Bergström is one of the few former Western supporters of the Khmer Rouge who have publicly admitted to making a terrible mistake, and expressing regret.

He has offered this explanation as to what had clouded his judgment all those years ago in 1978, when he was a guest of Pol Pot:

“In retrospect, I think the whole trip was a propaganda trip and that we should never have undertaken the journey,” he said, according to the Dinner with Pol Pot exhibition.

“It remains a mystery to me that we could have been so fooled… We were fooled by the smiles, but maybe most of all by our own Mao-glasses.”

No comments:

Post a Comment