[Related]

Phnom Penh's pivot toward Beijing has less to do with the United States than hatred for Vietnam

[no, Tanner Greer, it's "follow the money"; the strength of the CPP regime and Hun Sen's relationship with Vietnam stands, with China's increasing interference re Vietnam , re the US, re Asean -- hitting 3 birds with one Cambodia stone].

[no, Tanner Greer, it's "follow the money"; the strength of the CPP regime and Hun Sen's relationship with Vietnam stands, with China's increasing interference re Vietnam , re the US, re Asean -- hitting 3 birds with one Cambodia stone].

...

The giant’s client

Why Cambodia has cosied up to China

And why it worries Cambodia’s neighbours

The Economist | 21 January 2017

“CAMBODIA is a thin piece of ham between two fat pieces of bread,” says a former Cambodian minister, as he stirs a glass of iced coffee. To Cambodia’s west is Thailand, which has more than four times as many people; the two countries have a dormant but unsettled border dispute. To the east is Vietnam, nearly six times as populous, which invaded Cambodia in 1979 and occupied it for ten years. So Cambodia has done what small countries always do: it has found a protector.

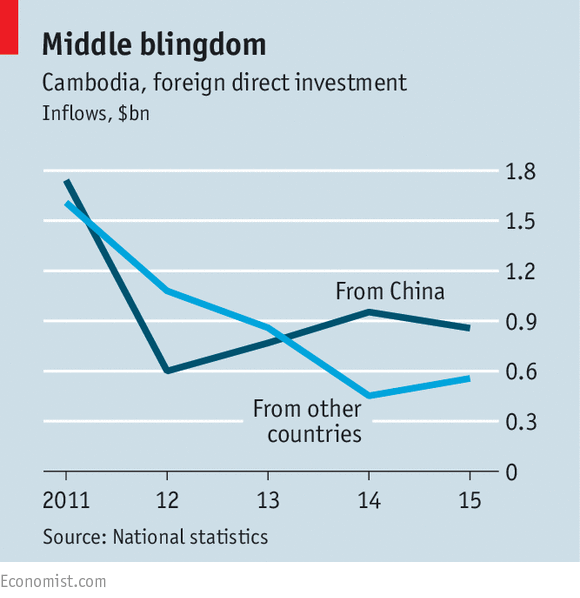

As long ago as 2006 Hun Sen, Cambodia’s prime minister, declared China his country’s “most trustworthy friend”. China’s past three presidents have all visited Cambodia, offering lavish aid and investment. The current one, Xi Jinping, declared Mr Hun Sen “an ironclad friend”. China is Cambodia’s biggest source of foreign direct investment by far: in 2015 it contributed a greater share to the total than all other countries combined (see chart). Cambodia has continued to accept Chinese largesse with glee, even as most of the rest of South-East Asia grows ever warier of its giant neighbour to the north (Laos, an even thinner slice of ham just north of Cambodia, is an exception). The ramifications of the strengthening relationship extend well beyond Cambodia’s borders.

China has long taken an interest in Cambodia. When America backed Lon Nol, a strongman who seized power in 1970, China supported his opponents: Norodom Sihanouk, the deposed king; and the Khmers Rouges, who displaced Lon Nol in 1975 and then murdered around 2m of their countrymen. China continued to support the Khmers Rouges even after the Vietnamese invasion pushed them out. But once Mr Hun Sen, a defector from the Khmers Rouges sheltered by Vietnam, fully consolidated power in the 1990s, China began assiduously courting him.

China provides military aid: uniforms, vehicles, loans to buy helicopters and a training facility in southern Cambodia. Between 2011 and 2015 Chinese firms funnelled nearly $5bn in loans and investment to Cambodia, accounting for around 70% of the total industrial investment in the country. Chinese firms run garment and food-processing factories and are also heavily involved in construction, mining, infrastructure and hydropower. Others hold at least 369,000 hectares of land concessions on which they grow sugar, rubber, paper and other crops.

The government is often willing to bend the rules for Chinese firms. One is developing a luxury resort inside a national park on the edges of Sihanoukville, the country’s main port. Another has won development rights over some 20% of Cambodia’s coastline. Human-rights groups allege that fishermen who had lived in the area for generations were summarily evicted, taken inland and told that they were now farmers.

Each side gets something out of the relationship. For Cambodia, the most obvious benefit is economic: it is poor and aiddependent; Chinese money lets it buy and build things it could not otherwise afford. Phay Siphan, a government spokesman, said last year: “Without Chinese aid, we go nowhere.”

But there are also two strategic benefits. First, Cambodia uses China as a counterweight to Vietnam. Among ordinary Cambodians, anti-Vietnamese sentiment runs deep. Many bitterly recall the Vietnamese occupation and some demand the return of “Kampuchea Krom”—the delta of the Mekong river, which today is part of Vietnam, but is home to many ethnic Cambodians and was for centuries part of the Khmer Empire. Since Vietnam harboured Mr Hun Sen, the opposition depicts him as a Vietnamese puppet. Closeness to China helps to defuse such claims.

Cambodia also uses China as a hedge against the West. Chinese money comes with no strings attached, unlike most Western donations, which are often linked to the government’s conduct. When Mr Hun Sen mounted a putsch against his coalition partners in the 1990s, Western donors suspended aid. China boosted it. Westerners may threaten to cut funding again if, as is likely, the government rigs elections next year (this week Mr Hun Sen again sued Sam Rainsy, the exiled leader of the main opposition party, for defamation, one of many steps seemingly intended to neuter his opponents). Chinese money will make it much easier for Mr Hun Sen to shrug off Western protests.

As for China, it gets a proxy within the ten-country Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Cambodia has repeatedly blocked ASEAN from making statements that criticise China’s expansive territorial claims in the South China Sea, even though they conflict with those of several other ASEAN members. Last year, less than a week after Cambodia endorsed China’s stance that competing maritime claims should be solved bilaterally, China gave Cambodia an aid package worth around $600m. (Mr Hun Sen insists the two were not related.)

China also seems to be eroding America’s clout in the region. For the past eight years Cambodia has held joint military exercises with America, but this week it announced that it would not do so this year or next. Cambodia and China, meanwhile, staged an eight-day joint exercise in November. The two countries also held their first joint naval exercises last year.

China also seems to be eroding America’s clout in the region. For the past eight years Cambodia has held joint military exercises with America, but this week it announced that it would not do so this year or next. Cambodia and China, meanwhile, staged an eight-day joint exercise in November. The two countries also held their first joint naval exercises last year.

ASEAN’s long-standing complaint, that Chinese influence on Cambodia hinders regional unity, is growing moot: over the South China Sea, at least, that unity appears to have disintegrated anyway. The Philippines, which took China to an international tribunal over its maritime claims, has reversed course. Its new president, Rodrigo Duterte, expresses contempt for America and affection for China. Vietnam, China’s other main adversary in the sea, recently pledged to resolve its maritime dispute bilaterally. Nobody yet knows what America’s policy on the South China Sea will be under Donald Trump, but increasingly it looks as if Cambodia has picked the winning side.

No comments:

Post a Comment