The Atlantic | October 2017 Issue

Eliot A. Cohen is a contributing editor at The Atlantic and

the director of the Strategic Studies Program at the Johns Hopkins

University School of Advanced International Studies. From 2007 to 2009,

he was the Counselor of the Department of State. He is the author of The Big Stick: The Limits of Soft Power and the Necessity of Military Force.

Donald Trump was right. He inherited a

mess. In January 2017, American foreign policy was, if not in crisis, in

big trouble. Strong forces were putting stress on the old global

political order: the rise of China to a power with more than half the

productive capacity of the United States (and defense spending to

match); the partial recovery of a resentful Russia under a skilled and

thuggish autocrat; the discrediting of Western elites by the financial

crash of 2008, followed by roiling populist waves, of which Trump

himself was part; a turbulent Middle East; economic dislocations

worldwide.

An American leadership that had partly discredited itself over the

past generation compounded these problems. The Bush administration’s war

against jihadist Islam had been undermined by reports of mistreatment

and torture; its Afghan campaign had been inconclusive; its invasion of

Iraq had been deeply compromised by what turned out to be a false

premise and three years of initial mismanagement.

The Obama

administration’s policy of retrenchment (described by a White House

official as “leading from behind”) made matters worse. The United States

was generally passive as a war that caused some half a million deaths

raged in Syria. The ripples of the conflict reached far into Europe, as

some 5 million Syrians fled the country. A red line about the use of

chemical weapons turned pale pink and vanished, as Iran and Russia

expanded their presence and influence in Syria ever more brazenly. A

debilitating freeze in defense spending, meanwhile, left two-thirds of

U.S. Army maneuver brigades unready to fight and Air Force pilots

unready to fly in combat.

These circumstances would have caused severe headaches for a competent and sophisticated successor. Instead, the United States got a president who had unnervingly promised a wall on the southern border (paid for by Mexico), the dismantlement of long-standing trade deals with both competitors and partners, a closer relationship with Vladimir Putin, and a ban on Muslims coming into the United States.

Some of these and Trump’s other wild pronouncements were quietly walked back or put on hold after his inauguration; one defense of Trump is that his deeds are less alarming than his words. But diplomacy is about words, and many of Trump’s words are profoundly toxic.

These circumstances would have caused severe headaches for a competent and sophisticated successor. Instead, the United States got a president who had unnervingly promised a wall on the southern border (paid for by Mexico), the dismantlement of long-standing trade deals with both competitors and partners, a closer relationship with Vladimir Putin, and a ban on Muslims coming into the United States.

Some of these and Trump’s other wild pronouncements were quietly walked back or put on hold after his inauguration; one defense of Trump is that his deeds are less alarming than his words. But diplomacy is about words, and many of Trump’s words are profoundly toxic.

Trump seems incapable of restraining himself from insulting foreign leaders. His slogan “America First” harks back to the isolationists of 1940, and foreign leaders know it. He can read speeches written for him by others, as he did in Warsaw on July 6, but he cannot himself articulate a worldview that goes beyond a teenager’s bluster. He lays out his resentments, insecurities, and obsessions on Twitter for all to see, opening up a gold mine to foreign governments seeking to understand and manipulate the American president.

Foreign governments have adapted. They flatter Trump outrageously. Their emissaries stay at his hotels and offer the Trump Organization abundant concessions (39 trademarks approved by China alone since Trump took office, including one for an escort service). They take him to military parades; they talk tough-guy-to-tough-guy; they show him the kind of deference that only someone without a center can crave. And so he flip-flops: Paris was no longer “so, so out of control, so dangerous” once he’d had dinner in the Eiffel Tower; Xi Jinping, during an April visit to Mar-a-Lago, went from being the leader of a parasitic country intent on ripping off American workers to being “a gentleman” who “wants to do the right thing.” (By July, Trump was back to bashing China, for doing “NOTHING” to help us.)

In almost every region of the world,

the administration has already left a mark, by blunder, inattention,

miscomprehension, or willfulness. Trump’s first official visit abroad

began in Saudi Arabia—a bizarre choice, when compared with established

democratic allies—where he and his senior advisers offered unreserved

praise for a kingdom that has close relations with the United States but

has also been the heartland of Islamist fanaticism since well before

9/11. The president full-throatedly took its side in a dispute with

Qatar, apparently ignorant of the vast American air base in the latter

country. He has seemed unaware that he is feeding an inchoate but

violent conflict between the Gulf kingdoms and a countervailing

coalition of Iran, Russia, Syria, Hezbollah, and even Turkey—which now

plans to deploy as many as 3,000 troops to Qatar, at its first base in

the Arab world since the collapse of the Ottoman empire at the end of

World War I.

The administration obsesses about defeating the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, and yet intends to sharply reduce the kinds of advice and support that are needed to rebuild the areas devastated by war in those same countries—support that might help prevent a future recurrence of Islamist fanaticism. The president, entranced by the chimera of an Israeli–Palestinian peace, has put his inexperienced and overburdened son-in-law, Jared Kushner, in charge of a process headed nowhere. Either ignorant or contemptuous of the deep-seated maladies that have long afflicted the Arab world, Trump embraces authoritarians like Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (“Love your shoes”) and seems to dismiss the larger problems of governance posed by the crises within Middle Eastern societies as internal issues irrelevant to the United States. A freedom agenda, in either its original Bush or subsequent Obama form, is dead.

The administration obsesses about defeating the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, and yet intends to sharply reduce the kinds of advice and support that are needed to rebuild the areas devastated by war in those same countries—support that might help prevent a future recurrence of Islamist fanaticism. The president, entranced by the chimera of an Israeli–Palestinian peace, has put his inexperienced and overburdened son-in-law, Jared Kushner, in charge of a process headed nowhere. Either ignorant or contemptuous of the deep-seated maladies that have long afflicted the Arab world, Trump embraces authoritarians like Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (“Love your shoes”) and seems to dismiss the larger problems of governance posed by the crises within Middle Eastern societies as internal issues irrelevant to the United States. A freedom agenda, in either its original Bush or subsequent Obama form, is dead.

In Europe, the administration has picked a fight with the Continent’s most important democratic state, Germany (“Bad, very bad”). Trump is sufficiently despised in Great Britain, America’s most enduring ally, that he will reportedly defer a trip there until his press improves (it will not). Paralyzed by scandal and internal division, the administration has no coherent Russia policy: no plan for getting Moscow back out of the Middle East; no counter to Russian political subversion in Europe or the United States; no response to reports of new Russian meddling in Afghanistan. Rather than pushing back when the Russians announced in July that 755 U.S. government employees would be expelled, Trump expressed his thanks for saving taxpayers 755 salaries.

America’s new circumstances in Asia were not much better as this story went to press, in mid-August—and with the world on edge, they could quickly get much worse. Though North Korea is on the verge of developing a nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missile, Trump neglected to rally American allies to confront the problem during his two major trips abroad. His aides proclaimed that they had discovered the solution, Chinese intervention—apparently unaware of the repeated failure of that gambit in the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations. Trump did, however, take a break from a golfing holiday to threaten North Korea with “fire and fury” in the event that Kim Jong Un failed to pipe down. To accommodate a president fixated on economic deals, an anxious Japan has pledged investments that would result in American jobs. A prickly Australia, whose prime minister Trump snarled at during their first courtesy phone call, has edged further from its traditional alliance with America—an alliance that has been the cornerstone of its security since World War II. (In a gesture that may seem trivial but signifies much, in July Australia’s foreign minister, Julie Bishop, slapped at Trump for his ogling of the French president’s wife, suggesting that his admiring looks had gone unreciprocated.)

On issues that are truly global in scope, Trump has abdicated leadership and the moral high ground. The United States has managed to isolate itself on the topic of climate change, by the tone of its pronouncements no less than by its precipitous exit from the Paris Agreement. As for human rights, the president has taken only cursory notice of the two arrests of the Russian dissident Alexei Navalny or the death of the Chinese Nobel Prize winner and prisoner of conscience Liu Xiaobo. Trump did not object after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s security detail beat American protesters on American soil, in Washington, D.C. In April, he reportedly told Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte, who has used death squads to deal with offenders of local narcotics laws, that he was doing an “unbelievable job on the drug problem.” Trump’s secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, made it clear in his first substantive speech to State Department employees that American values are now of at best secondary importance to “American interests,” presumably economic, in the conduct of foreign policy.

The Compounding Risk of Crisis

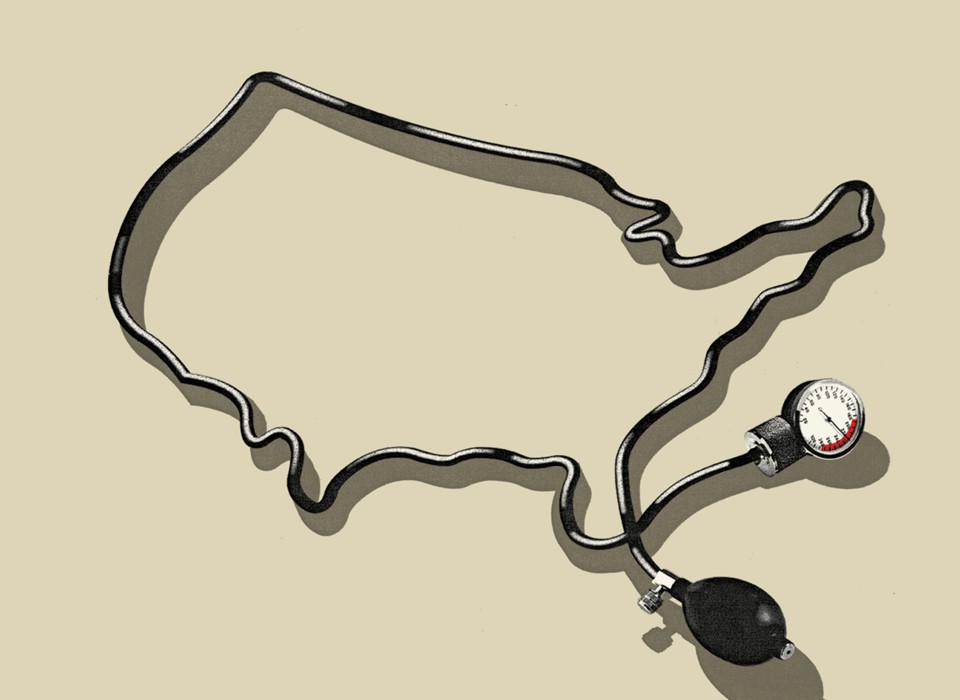

Matters will not improve. Trump will not learn, will not moderate, will not settle into normal patterns of behavior. And for all the rot that is visible in America’s standing and ability to influence global affairs, more is spreading beneath the surface. Even when Trump’s foreign policy looks shakily mediocre rather than downright crazy, it is afflicting the U.S. with a condition not unlike untreated high blood pressure. Enormous foreign-policy failures are like heart attacks: unexpected and dangerous discontinuities following years of neglect and hidden malady. The vertigo and throbbing pulse one feels today augur something much worse tomorrow.To a degree rarely appreciated outside Washington, it is virtually impossible to conduct an effective foreign policy without political appointees at the assistant-secretary rank who share a president’s conceptions and will implement his agenda. As of mid-August, the administration had yet to even nominate a new undersecretary of state for political affairs; assistant secretaries for Near Eastern, East Asian and Pacific, or Western Hemisphere Affairs; or ambassadors to Germany, India, or Saudi Arabia. At lower levels, the State Department is being actively thinned out—2,300 jobs are slated for elimination—and is losing experience by the week as disaffected professionals quietly leave.

High-level diplomatic contact with

allies and adversaries alike has withered. Meanwhile, for fear of

contradicting him, Trump’s underlings avoid saying too much publicly. As

a result, the administration’s foreign policy will continue to be as

opaque externally as it is confused internally.

One consequence will be a corresponding confusion on the part

of foreign powers about the administration’s goals, commitments, and

red lines—and the likely misinterpretation of stray signals. Even

well-run administrations can fail to communicate their intentions

clearly, with dire consequences. On July 25, 1990, the American

ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, met with Saddam Hussein. Glaspie

assured Saddam of President George H. W. Bush’s friendship and, although

the administration was concerned about a possible Iraqi attack on

Kuwait, blandly remarked that “we have no opinion on the Arab–Arab

conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.” A week later,

Saddam’s troops invaded Kuwait, and he was surprised when Bush did not

take it well. Again, this happened in a competent administration. One

shudders to think what the Trump equivalent might be with regard to,

say, Chinese aggression in the South China Sea.

The first Bush

administration recovered from the disaster of the Iraqi invasion of

Kuwait because it was an effective and cohesive team of highly

experienced professionals—Brent Scowcroft, James Baker, Dick Cheney—led

by a prudent and disciplined president. They built a coalition,

reassured and mobilized allies, placated neutrals, and planned and

executed a war. They disagreed with one another in open and productive

ways. They shrewdly used the career civil servants and able political

appointees who served them energetically and well. Even so, the war’s

ragged end and unexpected consequences are with us still.

Add to this fractured foundation

the erratic behavior of the president himself, who will be less and

less likely to accede to (or even hear) contrary advice as he passes

more time in the Oval Office. Septuagenarian tycoons do not change

fundamental qualities of their personalities: They are who they are. Nor

is someone who has spent a career in charge of a small, family-run

corporation without shareholders likely to pay much attention to

external views. These arguments have been well ventilated. But what many

people have not weighed adequately is the effect of the White House

itself, the trappings and the aura, on those who inhabit it. After an

initial period of awe, presidents become more confident that they know

what they’re doing. Particularly for someone whose ego knows few bounds,

it can be a dangerously intoxicating place.

Consider this contrast: In July 2005, I published in The Washington Post a searing critique of the Bush administration’s conduct of the Iraq War. The besieged defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld, did not fire me from the Defense Policy Board, a senior advisory committee to the Department of Defense, on which I served. Within months I was advising the National Security Council staff, and eventually Secretary Condoleezza Rice asked me to serve in one of the most senior positions in the Department of State without a murmur of disapproval from the White House. This reflected less my value to the administration than the large-spiritedness of President George W. Bush and those who worked for him, and their awareness that expressing criticism or dissent was an act of patriotism, not personal betrayal.

Trump unrestrained is of course a frightening prospect. His instincts are not reliable—if they were, he and his campaign would have kept their distance from Russian operatives. A man who has presided over failed casinos, a collapsed airline, and a sham university is not someone who knows when to step back from the brink. His domestic political circumstances, already bad, seem likely to deteriorate further, which will only make him more angry, and perhaps more apt to take risks. In a fit of temper or in the grip of spectacular misjudgment—possibly influenced by what he’s just seen on TV—he could stumble into or launch an uncontrollable war.

In one of the worst scenarios, Trump, as a result of his alternating overtures to and belligerence toward China, might bring about a conflict with Xi Jinping, who is consolidating his own power in a way not seen since the days of Mao Zedong. Military conflict between rising and preeminent global powers is hardly anomalous, after all, and the Chinese are no longer in the mood to accept American hegemony. In 1990, when George H. W. Bush confronted Saddam, an isolated dictator, a paralyzed Russia and weak China were powerless to interfere. He had at his disposal the American military at the peak of its post–Cold War strength, and a ready set of allies. The United States has grown used to wars with limited risk against minor and isolated rivals. A conflict with China would be something altogether different.

The Damage That Cannot Be Undone

This dangerous and dispiriting chapter in American history will end, in eight years or four—or perhaps in two or even one, if Trump is impeached or removed under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. But what will follow? Will the United States recover within a few years, as it did from the disgrace of Richard Nixon’s resignation and the fecklessness of Jimmy Carter during the Iranian hostage crisis? Alas, that is unlikely. Even barring cataclysmic events, we will be living with the consequences of Trump’s tenure as chief executive and commander in chief for decades. Damage will continue to appear long after he departs the scene.Americans, after trying every other alternative, can always be counted on to do the right thing, Winston Churchill supposedly said. But who will count on that now, after the victory of a man like Trump? Other countries interpret Trump’s election as America’s repudiation of its role as guarantor of world order. Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland put it bluntly in a speech in June: “The fact that our friend and ally has come to question the very worth of its mantle of global leadership puts into sharper focus the need for the rest of us to set our own clear and sovereign course.”

But there is also

a more structural development that will make the recovery of America’s

global status difficult: Trump is accelerating the decomposition of the

Republican foreign-policy and national-security establishment that began

in the 2016 campaign. Two public letters signed by some 150 of its

members during the spring and summer of last year denounced Trump not

merely for bad judgment but also for bad character. (I co-organized one

letter and assisted with the other.) Few who signed the letters cared to

recant after the election. The administration clearly wanted nothing to

do with any of them anyway, although it would have been wise to display

magnanimity and recruit some of them. Magnanimity is not, however, part

of the Trump playbook.

Establishments exist for a reason, and, within limits, they are good things. Despite what populists think, foreign policy is not, in fact, safely handed over to teams of ideologues or adventurous amateurs. Dean Acheson, Harry Truman’s secretary of state, who helped stabilize the post–World War II world, was not a corporate head who suddenly took an interest in what goes on abroad; neither was George Shultz, who, as Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state, helped orchestrate the final stage of the Cold War. Behind each of those men were hundreds of experts and practitioners who had thought hard about the world, and had experience steering the external relations of the Great Republic.

An elite consensus that spans both parties means a government that does not shift radically from administration to administration in its commitments to allies or to human rights, in its opposition to enemies, or in its support for international institutions; that has a sense of direction and purpose that transcends partisan politics; that can develop the political appointees our system uniquely depends on to staff the upper levels of government. As long as that elite is honest, able, open to new talent and to considered course alterations, and tolerant of dissent, it can provide consistency and stability.

Veterans of Trump’s administration

will include some patriots who knowingly took a reputational hit to save

the country from calamity—plus a large collection of mediocrities,

cynics, and trimmers willing to equivocate about American values and

interests, and indeed about their own beliefs. Many of them even now can

say, as the old Soviet joke had it, “I have my personal opinions, but I

assure you that I don’t agree with them.” Or, as one person explained

his decision to me as he began working for the administration, “It’s my

last shot at a big job.”

Most of these veterans, knowing what their former

friends and colleagues think of their decision, will be angrily

self-justifying. Many of the “Never Trumpers” who have held back from

working for an odious man will be disdainful. That is human nature. But

the upshot will be a Republican establishment riven, like the

conservative intellectual class more broadly, by antagonisms all the

more bitter because they rest as much on personal feelings of injury or

vindication as on principled beliefs. “Everything I’ve worked for for

two decades is being destroyed,” a senior Republican experienced in

foreign policy told Susan B. Glasser of Politico in March. One

should not expect from such individuals ready forgiveness of the

destroyers. All the while, the Democratic Party will be going through

its own turmoil as its foreign-policy experts, who had aligned

overwhelmingly with Hillary Clinton, come under pressure from members of

the party’s left wing, some of whose views on foreign affairs are not

that far from Trump’s.

There are many reasons to be appalled by President Trump, including his disregard for constitutional norms and decent behavior. But watching this unlikeliest of presidents strut on the treacherous stage of international politics is different from following the daily domestic chaos that is the Trump administration. Hearing him bully and brag, boast and bluster, threaten and lie, one feels a kind of dizziness, a sensation that underneath the throbbing pulse of routine scandal lies the potential for much worse. The kind of sensation, in fact, that accompanies dangerously high blood pressure, just before a sudden, excruciating pain.

Now I understand that, electoral voting system had screwed up my new country twice so far. US constitutional law, shouldn't have deviated from the real democratic principle re presidential election.

ReplyDeleteNanotechnology, Quantum computing,Outer space exploration, AI..etc.. will help lifting our country upward again soon I hope. And of course, by God's mercy.

Quantum computing is really only Analog computing in disguise. I bet some scientists are defrauding the investors and sponsors.

Delete