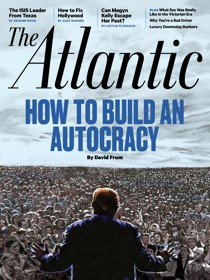

How to Build an Autocracy

The preconditions are

present in the U.S. today. Here’s the playbook Donald Trump could use to

set the country down a path toward illiberalism.

David Frum / The Atlantic | March 2017 issue

It’s 2021, and President Donald Trump

will shortly be sworn in for his second term. The 45th president has

visibly aged over the past four years. He rests heavily on his daughter

Ivanka’s arm during his infrequent public appearances.

Fortunately

for him, he did not need to campaign hard for reelection. His has been a

popular presidency: Big tax cuts, big spending, and big deficits have

worked their familiar expansive magic. Wages have grown strongly in the

Trump years, especially for men without a college degree, even if rising

inflation is beginning to bite into the gains. The president’s

supporters credit his restrictive immigration policies and his

TrumpWorks infrastructure program.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

The

president’s critics, meanwhile, have found little hearing for their

protests and complaints. A Senate investigation of Russian hacking

during the 2016 presidential campaign sputtered into inconclusive

partisan wrangling. Concerns about Trump’s purported conflicts of

interest excited debate in Washington but never drew much attention from

the wider American public.

Allegations of fraud and self-dealing in the TrumpWorks program, and elsewhere, have likewise been

shrugged off. The president regularly tweets out news of factory

openings and big hiring announcements: “I’m bringing back your jobs,” he

has said over and over. Voters seem to have believed him—and are

grateful.

Most Americans intuit that their president and his

relatives have become vastly wealthier over the past four years. But

rumors of graft are easy to dismiss. Because Trump has never released

his tax returns, no one really knows.

Anyway, doesn’t everybody do

it? On the eve of the 2018 congressional elections, WikiLeaks released

years of investment statements by prominent congressional Democrats

indicating that they had long earned above-market returns. As the air

filled with allegations of insider trading and crony capitalism, the

public subsided into weary cynicism. The Republicans held both houses of

Congress that November, and Trump loyalists shouldered aside the

pre-Trump leadership.

The business community learned its lesson

early. “You work for me, you don’t criticize me,” the president was

reported to have told one major federal contractor, after knocking

billions off his company’s stock-market valuation with an angry tweet.

Wise business leaders take care to credit Trump’s personal leadership

for any good news, and to avoid saying anything that might displease the

president or his family.

The

media have grown noticeably more friendly to Trump as well. The

proposed merger of AT&T and Time Warner was delayed for more than a

year, during which Time Warner’s CNN unit worked ever harder to meet

Trump’s definition of fairness. Under the agreement that settled the

Department of Justice’s antitrust complaint against Amazon, the

company’s founder, Jeff Bezos, has divested himself of The Washington Post.

The paper’s new owner—an investor group based in Slovakia—has closed

the printed edition and refocused the paper on municipal politics and

lifestyle coverage.

Meanwhile, social media circulate ever-wilder rumors. Some people believe them; others don’t. It’s hard work to ascertain what is true.

Meanwhile, social media circulate ever-wilder rumors. Some people believe them; others don’t. It’s hard work to ascertain what is true.

Nobody’s

repealed the First Amendment, of course, and Americans remain as free

to speak their minds as ever—provided they can stomach seeing their

timelines fill up with obscene abuse and angry threats from the

pro-Trump troll armies that police Facebook and Twitter. Rather than

deal with digital thugs, young people increasingly drift to less

political media like Snapchat and Instagram.

Trump-critical media do continue to find elite audiences. Their

investigations still win Pulitzer Prizes; their reporters accept

invitations to anxious conferences about corruption, digital-journalism

standards, the end of nato, and the rise

of populist authoritarianism. Yet somehow all of this earnest effort

feels less and less relevant to American politics. President Trump

communicates with the people directly via his Twitter account, ushering

his supporters toward favorable information at Fox News or Breitbart.

Despite the hand-wringing, the country has in many ways changed much

less than some feared or hoped four years ago. Ambitious Republican

plans notwithstanding, the American social-welfare system, as most

people encounter it, has remained largely intact during Trump’s first

term. The predicted wave of mass deportations of illegal immigrants

never materialized. A large illegal workforce remains in the country,

with the tacit understanding that so long as these immigrants avoid

politics, keeping their heads down and their mouths shut, nobody will

look very hard for them.

“The benefit of controlling a modern state is less the power to persecute the innocent, more the power to protect the guilty.”

African

Americans, young people, and the recently naturalized encounter

increasing difficulties casting a vote in most states. But for all the

talk of the rollback of rights, corporate America still seeks diversity

in employment. Same-sex marriage remains the law of the land. Americans

are no more and no less likely to say “Merry Christmas” than they were

before Trump took office.

People crack jokes about Trump’s

National Security Agency listening in on them. They cannot deeply mean

it; after all, there’s no less sexting in America today than four years

ago. Still, with all the hacks and leaks happening these days—particularly to the politically

outspoken—it’s just common sense to be careful what you say in an email

or on the phone. When has politics not been a dirty business? When have

the rich and powerful not mostly gotten their way? The smart thing to do

is tune out the political yammer, mind your own business, enjoy a

relatively prosperous time, and leave the questions to the

troublemakers.

In an 1888 lecture, James

Russell Lowell, a founder of this magazine, challenged the happy

assumption that the Constitution was a “machine that would go of

itself.” Lowell was right. Checks and balances is a metaphor, not a mechanism.

Everything imagined above—and everything described below—is possible only if many people other than Donald Trump agree to permit it. It can all be stopped, if individual citizens and public officials make the right choices. The story told here, like that told by Charles Dickens’s Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, is a story not of things that will be, but of things that may be. Other paths remain open. It is up to Americans to decide which one the country will follow.

No society, not even one as rich and fortunate as the United States has been, is guaranteed a successful future. When early Americans wrote things like “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty,” they did not do so to provide bromides for future bumper stickers. They lived in a world in which authoritarian rule was the norm, in which rulers habitually claimed the powers and assets of the state as their own personal property.

Everything imagined above—and everything described below—is possible only if many people other than Donald Trump agree to permit it. It can all be stopped, if individual citizens and public officials make the right choices. The story told here, like that told by Charles Dickens’s Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, is a story not of things that will be, but of things that may be. Other paths remain open. It is up to Americans to decide which one the country will follow.

No society, not even one as rich and fortunate as the United States has been, is guaranteed a successful future. When early Americans wrote things like “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty,” they did not do so to provide bromides for future bumper stickers. They lived in a world in which authoritarian rule was the norm, in which rulers habitually claimed the powers and assets of the state as their own personal property.

The

exercise of political power is different today than it was then—but

perhaps not so different as we might imagine. Larry Diamond, a

sociologist at Stanford, has described the past decade as a period of

“democratic recession.” Worldwide, the number of democratic states has

diminished. Within many of the remaining democracies, the quality of

governance has deteriorated.

What

has happened in Hungary since 2010 offers an example—and a blueprint

for would-be strongmen. Hungary is a member state of the European Union

and a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights. It has

elections and uncensored internet. Yet Hungary is ceasing to be a free

country.

The

transition has been nonviolent, often not even very dramatic. Opponents

of the regime are not murdered or imprisoned, although many are harassed

with building inspections and tax audits. If they work for the

government, or for a company susceptible to government pressure, they

risk their jobs by speaking out. Nonetheless, they are free to emigrate

anytime they like. Those with money can even take it with them. Day in

and day out, the regime works more through inducements than through

intimidation. The courts are packed, and forgiving of the regime’s

allies. Friends of the government win state contracts at high prices and

borrow on easy terms from the central bank. Those on the inside grow

rich by favoritism; those on the outside suffer from the general

deterioration of the economy. As one shrewd observer told me on a recent

visit, “The benefit of controlling a modern state is less the power to

persecute the innocent, more the power to protect the guilty."

Prime

Minister Viktor Orbán’s rule over Hungary does depend on elections.

These remain open and more or less free—at least in the sense that

ballots are counted accurately. Yet they are not quite fair. Electoral

rules favor incumbent power-holders in ways both obvious and subtle.

Independent media lose advertising under government pressure; government

allies own more and more media outlets each year. The government

sustains support even in the face of bad news by artfully generating an

endless sequence of controversies that leave culturally conservative

Hungarians feeling misunderstood and victimized by liberals, foreigners,

and Jews.

If this were happening in Honduras, we’d know what to call it. It’s happening here instead, and so we are baffled.

You

could tell a similar story of the slide away from democracy in South

Africa under Nelson Mandela’s successors, in Venezuela under the

thug-thief Hugo Chávez, or in the Philippines under the murderous

Rodrigo Duterte. A comparable transformation has recently begun in

Poland, and could come to France should Marine Le Pen, the National

Front’s candidate, win the presidency.

Outside the Islamic world,

the 21st century is not an era of ideology. The grand utopian visions of

the 19th century have passed out of fashion. The nightmare totalitarian

projects of the 20th have been overthrown or have disintegrated,

leaving behind only outdated remnants: North Korea, Cuba. What is

spreading today is repressive kleptocracy, led by rulers motivated by

greed rather than by the deranged idealism of Hitler or Stalin or Mao.

Such rulers rely less on terror and more on rule-twisting, the

manipulation of information, and the co-optation of elites.

The United States is of course a very robust democracy. Yet no human contrivance is tamper-proof, a constitutional democracy least of all. Some features of the American system hugely inhibit the abuse of office: the separation of powers within the federal government; the division of responsibilities between the federal government and the states. Federal agencies pride themselves on their independence; the court system is huge, complex, and resistant to improper influence.

The United States is of course a very robust democracy. Yet no human contrivance is tamper-proof, a constitutional democracy least of all. Some features of the American system hugely inhibit the abuse of office: the separation of powers within the federal government; the division of responsibilities between the federal government and the states. Federal agencies pride themselves on their independence; the court system is huge, complex, and resistant to improper influence.

Yet the American system is also perforated

by vulnerabilities no less dangerous for being so familiar. Supreme

among those vulnerabilities is reliance on the personal qualities of the

man or woman who wields the awesome powers of the presidency. A British

prime minister can lose power in minutes if he or she forfeits the

confidence of the majority in Parliament. The president of the United

States, on the other hand, is restrained first and foremost by his own

ethics and public spirit. What happens if somebody comes to the high

office lacking those qualities?

Over the past generation, we have

seen ominous indicators of a breakdown of the American political system:

the willingness of congressional Republicans to push the United States

to the brink of a default on its national obligations in 2013 in order

to score a point in budget negotiations; Barack Obama’s assertion of a

unilateral executive power to confer legal status upon millions of

people illegally present in the United States—despite his own prior

acknowledgment that no such power existed.

Donald

Trump, however, represents something much more radical. A president who

plausibly owes his office at least in part to a clandestine

intervention by a hostile foreign intelligence service? Who uses the

bully pulpit to target individual critics? Who creates blind trusts that

are not blind, invites his children to commingle private and public

business, and somehow gets the unhappy members of his own political

party either to endorse his choices or shrug them off? If this were

happening in Honduras, we’d know what to call it. It’s happening here

instead, and so we are baffled.

Video: David Frum on Donald Trump’s Authoritarian Tendencies

“Ambition must be made

to counteract ambition.” With those words, written more than 200 years

ago, the authors of the Federalist Papers explained the most important

safeguard of the American constitutional system. They then added this

promise: “In republican government, the legislative authority

necessarily predominates.” Congress enacts laws, appropriates funds,

confirms the president’s appointees. Congress can subpoena records,

question officials, and even impeach them. Congress can protect the

American system from an overbearing president.

But will it?

As

politics has become polarized, Congress has increasingly become a check

only on presidents of the opposite party. Recent presidents enjoying a

same-party majority in Congress—Barack Obama in 2009 and 2010, George W.

Bush from 2003 through 2006—usually got their way. And congressional

oversight might well be performed even less diligently during the Trump

administration.

The first reason to fear weak diligence is the

oddly inverse relationship between President Trump and the congressional

Republicans. In the ordinary course of events, it’s the incoming

president who burns with eager policy ideas. Consequently, it’s the

president who must adapt to—and often overlook—the petty human

weaknesses and vices of members of Congress in order to advance his

agenda. This time, it will be Paul Ryan, the speaker of the House, doing

the advancing—and consequently the overlooking.

Trump

has scant interest in congressional Republicans’ ideas, does not share

their ideology, and cares little for their fate. He can—and would—break

faith with them in an instant to further his own interests. Yet here

they are, on the verge of achieving everything they have hoped to

achieve for years, if not decades. They owe this chance solely to

Trump’s ability to deliver a crucial margin of votes in a handful of

states—Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—which has provided a party

that cannot win the national popular vote a fleeting opportunity to act

as a decisive national majority. The greatest risk to all their projects

and plans is the very same X factor that gave them their opportunity:

Donald Trump, and his famously erratic personality. What excites Trump

is his approval rating, his wealth, his power. The day could come when

those ends would be better served by jettisoning the institutional

Republican Party in favor of an ad hoc populist coalition, joining

nationalism to generous social spending—a mix that’s worked well for

authoritarians in places like Poland. Who doubts Trump would do it? Not

Paul Ryan. Not Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader. For the

first time since the administration of John Tyler in the 1840s, a

majority in Congress must worry about their president defecting from them rather than the other way around.

A scandal involving the president could likewise wreck everything that Republican congressional leaders have waited years to accomplish. However deftly they manage everything else, they cannot prevent such a scandal. But there is one thing they can do: their utmost not to find out about it.

A scandal involving the president could likewise wreck everything that Republican congressional leaders have waited years to accomplish. However deftly they manage everything else, they cannot prevent such a scandal. But there is one thing they can do: their utmost not to find out about it.

“Do you have any

concerns about Steve Bannon being in the White House?,” CNN’s Jake

Tapper asked Ryan in November. “I don’t know Steve Bannon, so I have no

concerns,” answered the speaker. “I trust Donald’s judgment.”

Asked on 60 Minutes

whether he believed Donald Trump’s claim that “millions” of illegal

votes had been cast, Ryan answered: “I don’t know. I’m not really

focused on these things.”

What about Trump’s conflicts of

interest? “This is not what I’m concerned about in Congress,” Ryan said

on CNBC. Trump should handle his conflicts “however he wants to.”

Ryan

has learned his prudence the hard way. Following the airing of Trump’s

past comments, caught on tape, about his forceful sexual advances on

women, Ryan said he’d no longer campaign for Trump. Ryan’s net

favorability rating among Republicans dropped by 28 points in less than

10 days. Once unassailable in the party, he suddenly found himself

disliked by 45 percent of Republicans.

As Ryan’s cherished plans

move closer and closer to presidential signature, Congress’s

subservience to the president will likely intensify. Whether it’s

allegations of Russian hacks of Democratic Party internal

communications, or allegations of self-enrichment by the Trump family,

or favorable treatment of Trump business associates, the Republican

caucus in Congress will likely find itself conscripted into serving as

Donald Trump’s ethical bodyguard.

The Senate historically has

offered more scope to dissenters than the House. Yet even that

institution will find itself under pressure. Two of the Senate’s most

important Republican Trump skeptics will be up for reelection in 2018:

Arizona’s Jeff Flake and Texas’s Ted Cruz. They will not want to provoke

a same-party president—especially not in a year when the president’s

party can afford to lose a seat or two in order to discipline

dissenters. Mitch McConnell is an even more results-oriented politician

than Paul Ryan—and his wife, Elaine Chao, has been offered a Cabinet

position, which might tilt him further in Trump’s favor.

Ambition

will counteract ambition only until ambition discovers that conformity

serves its goals better. At that time, Congress, the body expected to

check presidential power, may become the president’s most potent

enabler.

Discipline within the congressional ranks will be

strictly enforced not only by the party leadership and party donors, but

also by the overwhelming influence of Fox News. Trump versus Clinton

was not 2016’s only contest between an overbearing man and a restrained

woman. Just such a contest was waged at Fox, between Sean Hannity and

Megyn Kelly. In both cases, the early indicators seemed to favor the

women. Yet in the end it was the men who won, Hannity even more

decisively than Trump. Hannity’s show, which became an unapologetic

infomercial for Trump, pulled into first place on the network in

mid-October. Kelly’s show tumbled to fifth place, behind even The Five,

a roundtable program that airs at 5 p.m. Kelly landed on her feet, of

course, but Fox learned its lesson: Trump sells; critical coverage does

not. Since the election, the network has awarded Kelly’s former 9 p.m.

time slot to Tucker Carlson, who is positioning himself as a Trump

enthusiast in the Hannity mold.

A president determined to thwart the law to protect himself and those in his circle has many means to do so.

From

the point of view of the typical Republican member of Congress, Fox

remains all-powerful: the single most important source of visibility and

affirmation with the voters whom a Republican politician cares about.

In 2009, in the run-up to the Tea Party insurgency, South Carolina’s Bob

Inglis crossed Fox, criticizing Glenn Beck and telling people at a

town-hall meeting that they should turn his show off. He was drowned out

by booing, and the following year, he lost his primary with only 29

percent of the vote, a crushing repudiation for an incumbent untouched

by any scandal.

Fox is reinforced by a carrier fleet of supplementary institutions: super pacs,

think tanks, and conservative web and social-media presences, which now

include such former pariahs as Breitbart and Alex Jones. So long as the

carrier fleet coheres—and unless public opinion turns sharply against

the president—oversight of Trump by the Republican congressional

majority will very likely be cautious, conditional, and limited.

Donald Trump will not

set out to build an authoritarian state. His immediate priority seems

likely to be to use the presidency to enrich himself. But as he does so,

he will need to protect himself from legal risk. Being Trump, he will

also inevitably wish to inflict payback on his critics. Construction of

an apparatus of impunity and revenge will begin haphazardly and

opportunistically. But it will accelerate. It will have to.If Congress is quiescent, what can Trump do? A better question, perhaps, is what can’t he do?

Newt

Gingrich, the former speaker of the House, who often articulates

Trumpist ideas more candidly than Trump himself might think prudent,

offered a sharp lesson in how difficult it will be to enforce laws

against an uncooperative president. During a radio roundtable in

December, on the topic of whether it would violate anti-nepotism laws to

bring Trump’s daughter and son-in-law onto the White House staff,

Gingrich said: The president “has, frankly, the power of the pardon. It

is a totally open power, and he could simply say, ‘Look, I want them to

be my advisers. I pardon them if anybody finds them to have behaved

against the rules. Period.’ And technically, under the Constitution, he

has that level of authority.”

That statement is true, and it

points to a deeper truth: The United States may be a nation of laws, but

the proper functioning of the law depends upon the competence and

integrity of those charged with executing it. A president determined to

thwart the law in order to protect himself and those in his circle has

many means to do so.

The power of the pardon, deployed to defend

not only family but also those who would protect the president’s

interests, dealings, and indiscretions, is one such means. The powers of

appointment and removal are another. The president appoints and can

remove the commissioner of the IRS. He appoints and can remove the

inspectors general who oversee the internal workings of the Cabinet

departments and major agencies. He appoints and can remove the 93 U.S.

attorneys, who have the power to initiate and to end federal

prosecutions. He appoints and can remove the attorney general, the

deputy attorney general, and the head of the criminal division at the

Department of Justice.

There

are hedges on these powers, both customary and constitutional,

including the Senate’s power to confirm (or not) presidential

appointees. Yet the hedges may not hold in the future as robustly as

they have in the past.

Senators of the president’s party

traditionally have expected to be consulted on the U.S.-attorney picks

in their states, a highly coveted patronage plum. But the U.S. attorneys

of most interest to Trump—above all the ones in New York and New

Jersey, the locus of many of his businesses and bank dealings—come from

states where there are no Republican senators to take into account. And

while the U.S. attorneys in Florida, home to Mar-a-Lago and other Trump

properties, surely concern him nearly as much, if there’s one Republican

senator whom Trump would cheerfully disregard, it’s Marco Rubio.

The

traditions of independence and professionalism that prevail within the

federal law-enforcement apparatus, and within the civil service more

generally, will tend to restrain a president’s power. Yet in the years

ahead, these restraints may also prove less robust than they look.

Republicans in Congress have long advocated reforms to expedite the

firing of underperforming civil servants. In the abstract, there’s much

to recommend this idea. If reform is dramatic and happens in the next

two years, however, the balance of power between the political and the

professional elements of the federal government will shift, decisively,

at precisely the moment when the political elements are most aggressive.

The intelligence agencies in particular would likely find themselves

exposed to retribution from a president enraged at them for reporting on

Russia’s aid to his election campaign. “As you know from his other

career, Donald likes to fire people.” So New Jersey Governor Chris

Christie joked to a roomful of Republican donors at the party’s national

convention in July. It would be a mighty power—and highly useful.

The courts, though they might slowly be packed with judges inclined to hear the president’s arguments sympathetically, are also a check, of course. But it’s already difficult to hold a president to account for financial improprieties. As Donald Trump correctly told reporters and editors from The New York Times on November 22, presidents are not bound by the conflict-of-interest rules that govern everyone else in the executive branch.

The courts, though they might slowly be packed with judges inclined to hear the president’s arguments sympathetically, are also a check, of course. But it’s already difficult to hold a president to account for financial improprieties. As Donald Trump correctly told reporters and editors from The New York Times on November 22, presidents are not bound by the conflict-of-interest rules that govern everyone else in the executive branch.

Presidents

from Jimmy Carter onward have balanced this unique exemption with a

unique act of disclosure: the voluntary publication of their income-tax

returns. At a press conference on January 11, Trump made clear that he

will not follow that tradition. His attorney instead insisted that

everything the public needs to know is captured by his annual

financial-disclosure report, which is required by law for

executive-branch employees and from which presidents are not exempt. But

a glance at the reporting forms (you can read them yourself )

will show their inadequacy to Trump’s situation. They are written with

stocks and bonds in mind, to capture mortgage liabilities and deferred

executive compensation—not the labyrinthine deals of the Trump

Organization and its ramifying networks of partners and brand-licensing

affiliates. The truth is in the tax returns, and they will not be

forthcoming.

Even outright bribe-taking by an elected official is

surprisingly difficult to prosecute, and was made harder still by the

Supreme Court in 2016, when it overturned, by an 8–0 vote, the

conviction of former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell. McDonnell and his

wife had taken valuable gifts of cash and luxury goods from a favor

seeker. McDonnell then set up meetings between the favor seeker and

state officials who were in a position to help him. A jury had even

accepted that the “quid” was indeed “pro” the “quo”—an evidentiary

burden that has often protected accused bribe-takers in the past. The

McDonnells had been convicted on a combined 20 counts.

The

Supreme Court objected, however, that the lower courts had interpreted

federal anticorruption law too broadly. The relevant statute applied

only to “official acts.” The Court defined such acts very strictly, and

held that “setting up a meeting, talking to another official, or

organizing an event—without more—does not fit that definition of an

‘official act.’ ”

Trump

is poised to mingle business and government with an audacity and on a

scale more reminiscent of a leader in a post-Soviet republic than

anything ever before seen in the United States. Glimpses of his family’s

wealth-seeking activities will likely emerge during his presidency, as

they did during the transition. Trump’s Indian business partners dropped

by Trump Tower and posted pictures with the then-president-elect on

Facebook, alerting folks back home that they were now powers to be

reckoned with. The Argentine media reported that Trump had discussed the

progress of a Trump-branded building in Buenos Aires during a

congratulatory phone call from the country’s president. (A spokesman for

the Argentine president denied that the two men had discussed the

building on their call.) Trump’s daughter Ivanka sat in on a meeting

with the Japanese prime minister—a useful meeting for her, since a

government-owned bank has a large ownership stake in the Japanese

company with which she was negotiating a licensing deal.

Suggestive. Disturbing. But illegal, post-McDonnell? How many presidentially removable officials would dare even initiate an inquiry?

You

may hear much mention of the Emoluments Clause of the Constitution

during Trump’s presidency: “No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the

United States: And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust

under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any

present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any

King, Prince, or foreign State.”

But as written, this seems to

present a number of loopholes. First, the clause applies only to the

president himself, not to his family members. Second, it seems to govern

benefits only from foreign governments and state-owned enterprises, not

from private business entities. Third, Trump’s lawyers have argued that

the clause applies only to gifts and titles, not to business

transactions. Fourth, what does “the Consent of Congress” mean? If

Congress is apprised of an apparent emolument, and declines to do

anything about it, does that qualify as consent? Finally, how is this

clause enforced? Could someone take President Trump to court and demand

some kind of injunction? Who? How? Will the courts grant standing? The

clause seems to presume an active Congress and a vigilant public. What

if those are lacking?

It is essential to recognize that Trump will

use his position not only to enrich himself; he will enrich plenty of

other people too, both the powerful and—sometimes, for public

consumption—the relatively powerless. Venezuela, a stable democracy from

the late 1950s through the 1990s, was corrupted by a politics of

personal favoritism, as Hugo Chávez used state resources to bestow gifts

on supporters. Venezuelan state TV even aired a regular program to

showcase weeping recipients of new houses and free appliances. Americans

recently got a preview of their own version of that show as grateful

Carrier employees thanked then-President-elect Trump for keeping their

jobs in Indiana.

“I

just couldn’t believe that this guy … he’s not even president yet and

he worked on this deal with the company,” T. J. Bray, a 32-year-old

Carrier employee, told Fortune. “I’m just in shock. A lot of the

workers are in shock. We can’t believe something good finally happened

to us. It felt like a victory for the little people.”

Trump will

try hard during his presidency to create an atmosphere of personal

munificence, in which graft does not matter, because rules and

institutions do not matter. He will want to associate economic benefit

with personal favor. He will create personal constituencies, and

implicate other people in his corruption. That, over time, is what truly

subverts the institutions of democracy and the rule of law. If the

public cannot be induced to care, the power of the investigators serving

at Trump’s pleasure will be diminished all the more.

“The first task

for our new administration will be to liberate our citizens from the

crime and terrorism and lawlessness that threatens our communities.”

Those were Donald Trump’s words at the Republican National Convention.

The newly nominated presidential candidate then listed a series of

outrages and attacks, especially against police officers.

America was shocked to its core when our police officers in Dallas were so brutally executed. Immediately after Dallas, we’ve seen continued threats and violence against our law-enforcement officials. Law officers have been shot or killed in recent days in Georgia, Missouri, Wisconsin, Kansas, Michigan, and Tennessee.

On Sunday, more police were gunned down in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Three were killed, and three were very, very badly injured. An attack on law enforcement is an attack on all Americans. I have a message to every last person threatening the peace on our streets and the safety of our police: When I take the oath of office next year, I will restore law and order to our country.

You would never know from Trump’s

words that the average number of felonious killings of police during the

Obama administration’s tenure was almost one-third lower than it was in

the early 1990s, a decline that tracked with the general fall in

violent crime that has so blessed American society. There had been a

rise in killings of police in 2014 and 2015 from the all-time low in

2013—but only back to the 2012 level. Not every year will be the best on

record.

A mistaken belief that crime is

spiraling out of control—that terrorists roam at large in America and

that police are regularly gunned down—represents a considerable

political asset for Donald Trump. Seventy-eight percent of Trump voters

believed that crime had worsened during the Obama years.

Civil unrest will not be a problem for the Trump presidency. It will be a resource. Trump will likely want to enflame more of it.

In

true police states, surveillance and repression sustain the power of the

authorities. But that’s not how power is gained and sustained in

backsliding democracies. Polarization, not persecution, enables the

modern illiberal regime.

By guile or by instinct, Trump understands this.

Whenever Trump stumbles into some kind of trouble, he reacts by picking a divisive fight. The morning after The Wall Street Journal

published a story about the extraordinary conflicts of interest

surrounding Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, Trump tweeted that flag

burners should be imprisoned or stripped of their citizenship. That

evening, as if on cue, a little posse of oddballs obligingly burned

flags for the cameras in front of the Trump International Hotel in New

York. Guess which story dominated that day’s news cycle?

Civil

unrest will not be a problem for the Trump presidency. It will be a

resource. Trump will likely want not to repress it, but to publicize

it—and the conservative entertainment-outrage complex will eagerly

assist him. Immigration protesters marching with Mexican flags; Black

Lives Matter demonstrators bearing antipolice slogans—these are the

images of the opposition that Trump will wish his supporters to see. The

more offensively the protesters behave, the more pleased Trump will be.

Calculated outrage is an old political trick, but nobody in the history

of American politics has deployed it as aggressively, as repeatedly, or

with such success as Donald Trump. If there is harsh law enforcement by

the Trump administration, it will benefit the president not to the

extent that it quashes unrest, but to the extent that it enflames more

of it, ratifying the apocalyptic vision that haunted his speech at the

convention.

At a rally

in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in December, Trump got to talking about

Vladimir Putin. “And then they said, ‘You know he’s killed reporters,’ ”

Trump told the audience. “And I don’t like that. I’m totally against

that. By the way, I hate some of these people, but I’d never kill them. I

hate them. No, I think, no—these people, honestly—I’ll be honest. I’ll

be honest. I would never kill them. I would never do that. Ah, let’s

see—nah, no, I wouldn’t. I would never kill them. But I do hate them.”

In

the early days of the Trump transition, Nic Dawes, a journalist who has

worked in South Africa, delivered an ominous warning to the American

media about what to expect. “Get used to being stigmatized as

‘opposition,’ ” he wrote. “The basic idea is simple: to delegitimize

accountability journalism by framing it as partisan.”

The rulers

of backsliding democracies resent an independent press, but cannot

extinguish it. They may curb the media’s appetite for critical coverage

by intimidating unfriendly journalists, as President Jacob Zuma and

members of his party have done in South Africa. Mostly, however, modern

strongmen seek merely to discredit journalism as an institution, by

denying that such a thing as independent judgment can exist. All

reporting serves an agenda. There is no truth, only competing attempts

to grab power.

By filling the media space with bizarre inventions

and brazen denials, purveyors of fake news hope to mobilize potential

supporters with righteous wrath—and to demoralize potential opponents by

nurturing the idea that everybody lies and nothing matters. A would-be

kleptocrat is actually better served by spreading cynicism than by

deceiving followers with false beliefs: Believers can be disillusioned;

people who expect to hear only lies can hardly complain when a lie is

exposed. The inculcation of cynicism breaks down the distinction between

those forms of media that try their imperfect best to report the truth,

and those that purvey falsehoods for reasons of profit or ideology. The New York Times becomes the equivalent of Russia’s RT; The Washington Post of Breitbart; NPR of Infowars.

One

story, still supremely disturbing, exemplifies the falsifying method.

During November and December, the slow-moving California vote count

gradually pushed Hillary Clinton’s lead over Donald Trump in the

national popular vote further and further: past 1 million, past 1.5

million, past 2 million, past 2.5 million. Trump’s share of the vote

would ultimately clock in below Richard Nixon’s in 1960, Al Gore’s in

2000, John Kerry’s in 2004, Gerald Ford’s in 1976, and Mitt Romney’s in

2012—and barely ahead of Michael Dukakis’s in 1988.

This outcome

evidently gnawed at the president-elect. On November 27, Trump tweeted

that he had in fact “won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of

people who voted illegally.” He followed up that astonishing, and

unsubstantiated, statement with an escalating series of tweets and

retweets.

It’s hard to do justice to the breathtaking audacity of

such a claim. If true, it would be so serious as to demand a criminal

investigation at a minimum, presumably spanning many states. But of

course the claim was not true. Trump had not a smidgen of evidence

beyond his own bruised feelings and internet flotsam from flagrantly

unreliable sources. Yet once the president-elect lent his prestige to

the crazy claim, it became fact for many people. A survey by YouGov

found that by December 1, 43 percent of Republicans accepted the claim

that millions of people had voted illegally in 2016.

A clear

untruth had suddenly become a contested possibility [in the Cambodian context, use of word "Yuon" as racist]. When CNN’s Jeff

Zeleny correctly reported on November 28 that Trump’s tweet was

baseless, Fox’s Sean Hannity accused Zeleny of media bias—and then

proceeded to urge the incoming Trump administration to take a new tack

with the White House press corps, and to punish reporters like Zeleny.

“I think it’s time to reevaluate the press and maybe change the

traditional relationship with the press and the White House,” Hannity

said. “My message tonight to the press is simple: You guys are done.

You’ve been exposed as fake, as having an agenda, as colluding. You’re a

fake news organization.”

This was no idiosyncratic brain wave of

Hannity’s. The previous morning, Ari Fleischer, the former press

secretary in George W. Bush’s administration, had advanced a similar

idea in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, suggesting that the White

House could withhold credentials for its press conferences from media

outlets that are “too liberal or unfair.” Newt Gingrich recommended that

Trump stop giving press conferences altogether.

Twitter,

unmediated by the press, has proved an extremely effective communication

tool for Trump. And the whipping-up of potentially violent Twitter mobs

against media critics is already a standard method of Trump’s

governance. Megyn Kelly blamed Trump and his campaign’s social-media

director for inciting Trump’s fans against her to such a degree that she

felt compelled to hire armed guards to protect her family. I’ve talked

with well-funded Trump supporters who speak of recruiting a troll army

explicitly modeled on those used by Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and

Russia’s Putin to take control of the social-media space, intimidating

some critics and overwhelming others through a blizzard of doubt-casting

and misinformation. The WikiLeaks Task Force recently tweeted—then

hastily deleted—a suggestion that it would build a database to track

personal and financial information on all verified Twitter accounts, the

kind of accounts typically used by journalists at major media

organizations. It’s not hard to imagine how such compilations could be

used to harass or intimidate.

Even so, it seems unlikely that

President Trump will outright send the cameras away. He craves media

attention too much. But he and his team are serving notice that a new

era in government-media relations is coming, an era in which all

criticism is by definition oppositional—and all critics are to be

treated as enemies.

In an online article for The New York Review of Books,

the Russian-born journalist Masha Gessen brilliantly noted a

commonality between Donald Trump and the man Trump admires so much,

Vladimir Putin. “Lying is the message,” she wrote. “It’s not just

that both Putin and Trump lie, it is that they lie in the same way and

for the same purpose: blatantly, to assert power over truth itself.”

The lurid mass movements

of the 20th century—communist, fascist, and other—have bequeathed to

our imaginations an outdated image of what 21st-century authoritarianism

might look like.

Whatever else happens, Americans are not going

to assemble in parade-ground formations, any more than they will crank a

gramophone or dance the turkey trot. In a society where few people walk

to work, why mobilize young men in matching shirts to command the

streets? If you’re seeking to domineer and bully, you want your storm

troopers to go online, where the more important traffic is. Demagogues

need no longer stand erect for hours orating into a radio microphone.

Tweet lies from a smartphone instead.

“Populist-fueled democratic

backsliding is difficult to counter,” wrote the political scientists

Andrea Kendall-Taylor and Erica Frantz late last year. “Because it is

subtle and incremental, there is no single moment that triggers

widespread resistance or creates a focal point around which an

opposition can coalesce … Piecemeal democratic erosion, therefore,

typically provokes only fragmented resistance.” Their observation was

rooted in the experiences of countries ranging from the Philippines to

Hungary. It could apply here too.

If people retreat into private

life, if critics grow quieter, if cynicism becomes endemic, the

corruption will slowly become more brazen, the intimidation of opponents

stronger. Laws intended to ensure accountability or prevent graft or

protect civil liberties will be weakened.

If the president uses

his office to grab billions for himself and his family, his supporters

will feel empowered to take millions. If he successfully exerts power to

punish enemies, his successors will emulate his methods.

If

citizens learn that success in business or in public service depends on

the favor of the president and his ruling clique, then it’s not only

American politics that will change. The economy will be corrupted too,

and with it the larger culture. A culture that has accepted that graft

is the norm, that rules don’t matter as much as relationships with those

in power, and that people can be punished for speech and acts that

remain theoretically legal—such a culture is not easily reoriented back

to constitutionalism, freedom, and public integrity.

The

oft-debated question “Is Donald Trump a fascist?” is not easy to answer.

There are certainly fascistic elements to him: the subdivision of

society into categories of friend and foe; the boastful virility and the

delight in violence; the vision of life as a struggle for dominance

that only some can win, and that others must lose.

Yet there’s

also something incongruous and even absurd about applying the sinister

label of fascist to Donald Trump. He is so pathetically needy, so

shamelessly self-interested, so fitful and distracted. Fascism

fetishizes hardihood, sacrifice, and struggle—concepts not often

associated with Trump.

A would-be kleptocrat is better served by spreading cynicism than by deceiving followers.

Perhaps this is the wrong question. Perhaps the better question about Trump is not “What is he?” but “What will he do to us?”

By

all early indications, the Trump presidency will corrode public

integrity and the rule of law—and also do untold damage to American

global leadership, the Western alliance, and democratic norms around the

world. The damage has already begun, and it will not be soon or easily

undone. Yet exactly how much damage is allowed to be done is an open

question—the most important near-term question in American politics. It

is also an intensely personal one, for its answer will be determined by

the answer to another question: What will you do? And you? And you?

Of

course we want to believe that everything will turn out all right. In

this instance, however, that lovely and customary American assumption

itself qualifies as one of the most serious impediments to everything

turning out all right. If the story ends without too much harm to the

republic, it won’t be because the dangers were imagined, but because

citizens resisted.

The duty to resist should weigh most heavily

upon those of us who—because of ideology or partisan affiliation or some

other reason—are most predisposed to favor President Trump and his

agenda. The years ahead will be years of temptation as well as danger:

temptation to seize a rare political opportunity to cram through an

agenda that the American majority would normally reject. Who knows when

that chance will recur?

A constitutional regime is founded upon

the shared belief that the most fundamental commitment of the political

system is to the rules. The rules matter more than the outcomes. It’s

because the rules matter most that Hillary Clinton conceded the

presidency to Trump despite winning millions more votes. It’s because

the rules matter most that the giant state of California will accept the

supremacy of a federal government that its people rejected by an almost

two-to-one margin.

Perhaps the words of a founding father of

modern conservatism, Barry Goldwater, offer guidance. “If I should later

be attacked for neglecting my constituents’ ‘interests,’ ” Goldwater

wrote in The Conscience of a Conservative, “I shall reply that I

was informed their main interest is liberty and that in that cause I am

doing the very best I can.” These words should be kept in mind by those

conservatives who think a tax cut or health-care reform a sufficient

reward for enabling the slow rot of constitutional government.

Many

of the worst and most subversive things Trump will do will be highly

popular. Voters liked the threats and incentives that kept Carrier

manufacturing jobs in Indiana. Since 1789, the wisest American leaders

have invested great ingenuity in creating institutions to protect the

electorate from its momentary impulses toward arbitrary action: the

courts, the professional officer corps of the armed forces, the civil

service, the Federal Reserve—and undergirding it all, the guarantees of

the Constitution and especially the Bill of Rights. More than any

president in U.S. history since at least the time of Andrew Jackson,

Donald Trump seeks to subvert those institutions.

Trump and his

team count on one thing above all others: public indifference. “I think

people don’t care,” he said in September when asked whether voters

wanted him to release his tax returns. “Nobody cares,” he reiterated to 60 Minutes

in November. Conflicts of interest with foreign investments? Trump

tweeted on November 21 that he didn’t believe voters cared about that

either: “Prior to the election it was well known that I have interests

in properties all over the world. Only the crooked media makes this a

big deal!”

What happens in the next four years will depend heavily

on whether Trump is right or wrong about how little Americans care

about their democracy and the habits and conventions that sustain it. If

they surprise him, they can restrain him.

Public opinion, public

scrutiny, and public pressure still matter greatly in the U.S. political

system. In January, an unexpected surge of voter outrage thwarted plans

to neutralize the independent House ethics office. That kind of defense

will need to be replicated many times. Elsewhere in this issue,

Jonathan Rauch describes some of the networks of defense that Americans

are creating.

Get into the habit of telephoning your senators and

House member at their local offices, especially if you live in a red

state. Press your senators to ensure that prosecutors and judges are

chosen for their independence—and that their independence is protected.

Support laws to require the Treasury to release presidential tax returns

if the president fails to do so voluntarily. Urge new laws to clarify

that the Emoluments Clause applies to the president’s immediate family,

and that it refers not merely to direct gifts from governments but to

payments from government-affiliated enterprises as well. Demand an

independent investigation by qualified professionals of the role of

foreign intelligence services in the 2016 election—and the contacts, if

any, between those services and American citizens. Express your support

and sympathy for journalists attacked by social-media trolls, especially

women in journalism, so often the preferred targets. Honor civil

servants who are fired or forced to resign because they defied improper

orders. Keep close watch for signs of the rise of a culture of official

impunity, in which friends and supporters of power-holders are allowed

to flout rules that bind everyone else.

Those citizens who

fantasize about defying tyranny from within fortified compounds have

never understood how liberty is actually threatened in a modern

bureaucratic state: not by diktat and violence, but by the slow,

demoralizing process of corruption and deceit. And the way that liberty

must be defended is not with amateur firearms, but with an unwearying

insistence upon the honesty, integrity, and professionalism of American

institutions and those who lead them. We are living through the most

dangerous challenge to the free government of the United States that

anyone alive has encountered. What happens next is up to you and me.

Don’t be afraid. This moment of danger can also be your finest hour as a

citizen and an American.

Need to deport more Khmericans back to Cambodia.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.khmer440.com/chat_forum/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=58789

NEW AMERICA:

ReplyDeleteAmerica was GREAT until Donald Trump got

selected by Vladimir Putin !!!

Deported Khmerican wrote an open letter (published to the press) to US embassy in Cambodia to complain, but caught lying in the letter.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.khmer440.com/chat_forum/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=58789&sid=d11d6ed4c602bd14c8047e9e2c8d33c0&start=60

Deport drunk Fu.k-it back to hell hole in Hanoi !!!

ReplyDeletehttp://www.khmer440.com/chat_forum/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=58789&sid=d11d6ed4c602bd14c8047e9e2c8d33c0&start=60

ReplyDeleteSee? The lying Khmer just disappeared when the expats in Cambodia asked him simple questions.

-------

Re: Deported Khmerican felon whines about being denied tourist visa at US Embassy

Postby batshitcrazyweirdo » Fri Jan 27, 2017 6:22 pm

"BURP!!

Hold on there a minute, Hang man. You said the daughters only go to the USA in summer. So they've been here while you have been letting your wife at her prestigious ... company ... finish her ... program. What program is that?

To be honest, Hang, you sound full of shit to me. I'd like to know what the hell you are really talking about."